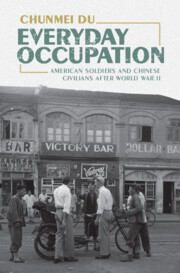

In late August 1945, as marines were beginning their occupation mission, American ambassador Patrick J. Hurley and Nationalist representative Zhang Zhizhong traveled to Yan’an to escort Mao Zedong to the Chongqing Negotiations. All rode together in a Jeep adorned with a large American flag, an iconic moment captured in a widely circulated profile picture (see Figure 3.1). Mao arrived in Chongqing on August 28 aboard a US military C-47 transport aircraft. The arduous negotiations, lasting forty-three days, culminated in the signing of the Double Tenth Agreement, which outlined the common goal of eventually establishing a political democracy in China and plans for a coalition government. However, armed struggles persisted throughout the peace talks, and the military situation in North China rapidly deteriorated. After signing the agreement, Mao immediately returned to Yan’an and delivered a report to the cadres, declaring that the CCP was ready to strike tit for tat.

Figure 3.1 Mao Zedong getting into a Jeep with Patrick Hurley, Zhang Zhizhong, and David Dean Barrett, en route to the Chongqing Negotiations, Yan’an, August 1945.

Figure 3.1Long description

He smiles at Zhang Zhizhong and Patrick Hurley, who are seated in the back of the Jeep. David D. Barrett stands to the right, ready to get into the driver’s seat. A group of U.S. servicemen and Chinese Communists watch from the background.

The determination to counteract any aggression was soon extended to what Mao called the US imperialists who supported the reactionary government of Chiang Kai-shek. Perhaps invoking the principle of “reciprocity,” the victorious Communist Party staged its first major military parade at Xiyuan Airport in Beijing on March 25, 1949. The event celebrated the liberation of the historic capital and foreshadowed the imminent liberation of the entire country. In a symbolic gesture – and perhaps a nod to his earlier ride with the Americans – Mao declined an invitation to ride in a more comfortable passenger car, opting instead for a Jeep. With a knowing smile, he remarked, “Isn’t it more meaningful to parade in our captured American Jeeps?”1 This remark, laden with satire, underscored his unmistakable pride and confidence in defeating the mighty Americans. This moment also revealed the uncanny power of the Jeep as both a potent military vehicle and a powerful cultural symbol.

There is perhaps no better visual symbol of the American military presence in postwar China than the iconic Jeep.2 Communist propaganda targeted the vehicle as the ultimate emblem of US imperialism: Driven recklessly by drunk soldiers, the speeding Jeep ran amok on the streets, killing innocent civilians while the driver escaped justice. In reality, traffic accidents caused by American military vehicles, which led to frequent injuries and deaths of locals, were indeed the most common trigger of grassroots tensions. Disputes with rickshaw pullers sometimes escalated into physical confrontations, and even manslaughter, sparking massive protests. While existing studies have demonstrated the impacts of these incidents on Chinese anti-American sentiments, the complex social, cultural, and technological dimensions of the Chinese encounter with the Jeep remain little explored. Foregrounding the Jeep’s rich materiality and symbolism, this chapter shows that the Chinese experience of the vehicle as a source of modern thrill and as a foreign military object blended early desires for a spectacle and a commodity with increasing nationalist sentiments against the American global empire and all its techno-industrial power, political hegemony, and military prowess.

When the Jeep arrived on postwar Chinese streets, it was an object of enchantment, first as a symbol of Allied victory and prestige, then as a cultural spectacle and popular commodity. However, following frequent incidents caused by drunk driving, speeding, and negligence, the Jeep/GI criminal duo became an instrument of intimidation and destruction, undermining China’s existing order. The relationships between GIs and rickshaw men, which mingled fantasy, patronage, rivalry, and conflict, eventually descended into violence and brutality. As disputes over speed limits, economic compensation, moral responsibilities, and legal justice intensified, the American military vehicle embroiled in local street politics became the ultimate symbol of prolonged American occupation trampling Chinese sovereignty.

The Lure of Speed

“A modern knight is a driver behind the wheels. This contemporary cavalier on the road is a young man named ‘Jeep Car (jipu ka) 吉普卡,’” a transliteration of the newly introduced American military vehicle, the Jeep.3 As elsewhere in the postwar world, the Jeep featured prominently in Chinese civilians’ initial experiences of American soldiers. In the autumn of 1945, residents of areas formerly occupied by the Japanese had their first encounter with the vehicle, as the liberating forces marched through city centers in open trucks and Jeeps. Chinese children’s first experiences of the Jeep echoed those of their counterparts in Japan, Korea, Germany, or France, who also chased after the vehicles hoping for goodies. Whether from Allied, defeated, or formerly colonized nations, these children were all war-worn and hungry.

During WWII, the Jeep became one of the most prominent symbols of the American military, what Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall called “America’s greatest contribution to modern warfare.”4 Showcasing the country’s superior technological and industrial power, with its world-class quality, design, and production, the Jeep was featured on magazine covers and postcards and in commercials and movie scenes.5 The iconic vehicle testified to America’s global military prowess and appeared in major victories, marches, and advances, together with commanders, soldiers, dignitaries, and stars worldwide: from General Dwight Eisenhower in the iconic Normandy landing and President Roosevelt during the groundbreaking Casablanca Conference to General George S. Patton’s legendary marches in North Africa. Chinese leaders also marched in Jeeps, headed by Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, as tens of thousands of soldiers shouted slogans of loyalty and devotion in military parades, further enhancing the vehicle’s prestige and elite status in China.6

On the India–Burma Road, Jeeps and Dodge trucks moved essential supplies to China through rugged mountains and dense jungles that had been cut off by the Japanese encirclement and created a lifeline for the continuing war effort. In 1943, with the help of the Jeep, Joseph Stilwell, the US commander in the CBI Theater, successfully relocated several divisions of the Chinese Expeditionary Force and war refugees through the difficult terrain of the rainforest from Myanmar to India. The ambulance aircraft, nicknamed “Flying Jeep,” was known for saving seriously injured soldiers due to its ability to take off from roads and fly at low altitude and speeds.7 Since the war, the American military had gifted and sold tens of thousands of Jeeps to China. At its peak, the Nationalist army owned more than thirty thousand military vehicles from American surplus supplies. In August 1946, China’s Transportation Department approved the use of the Jeep for commercial and private settings, albeit with some restrictions, including the need to show proof of legitimate purchase and the requirement to paint the surface black.8 From 1947 to 1948, the number of registered Jeeps in Shanghai ranged between 1,000 and 1,460, more than 5 percent of all motor vehicles.9

Automobiles remained a novelty to most of the Chinese population, even the intellectual elites. As Jeeps poured into postwar cities, local media introduced the shining invention to its many enthusiastic spectators and consumers. Some reports focused on the technological power of the vehicle, highlighting its origin, design, mechanics, features, and uses.10 Unlike a regular car, the Jeep did not have fancy equipment or decorations, but was rather depicted as “an unbreakable, unspoilable tough guy.”11 Other advertisements, including those from the United States Information Service, boasted its versatility, calling it the “Omnipotent Jeep” that could be used everywhere, in agricultural tasks like plowing, threshing, and fertilizing, as well as in snow removal, power generation, herding cows, and fire extinction.12 As readers gazed in awe at the small but formidable vehicle featured in popular periodicals, the Jeep indeed appeared not only undefeatable, but also all-powerful. These descriptions of the Jeep’s qualities mirrored those found in American commercials. In postwar America, the Willys-Overland Corporation launched a glamourizing advertisement campaign to pave the way for the Jeep’s transition to civilian life. In shiny magazine spaces, Jeeps posed together with long-limbed American beauties drinking Coca-Cola or waving in their bathing costumes to their male friends. The Universal Jeep with narrow and uncomfortable seating, designed for rough driving on bumpy roads, was now celebrated for its versatile performance, economic operation, functional smartness, and ultimately “a brand new thrill in driving.”13

Associated with the latest technologies, the Jeep became a prestigious commodity on the Chinese market. A comical piece in a Shanghai newspaper supplementary recorded a late-night conversation in a parking lot between “Jeep Big Brother, Ford Tycoon, and Dodge Coolie.” Ford, the American passenger vehicle, complains about being fed with charcoal due to shortages of gasoline, as well as the instability of changing bosses frequently – each losing power one after another. The youngest and now most popular Jeep mocks the worn-out coolie truck, which had been working in the city the longest: “You do not look like an American at all!”14 Chinese perceptions of the vehicle were influenced by racial underpinnings: It was not only linked to an American identity, but also to a white American experience. This mirrors the racial stereotypes prevalent in the portrayal of black truck drivers in the CBI Theater, where such biases were evident. Black drivers were seen as naturally suited for hard labor, capable of enduring extreme heat and harsh environments, and possessing happy-go-lucky personalities who sang, drove, and drank. All of these traits made them excellent truck drivers in the Theater, but not operators of the mighty Jeep.15

If the original Jeep embodied American democracy, as commanders and soldiers rode in the front seat in the open air, with minimum comfort but uncontained freedom and limitless possibilities to explore and expand, in its afterlife of civilian use in China, the Jeep was often converted into a fancier passenger vehicle with padded seats and luxurious accessories, in addition to a hired driver. As Marshall McLuhan has shown, in Americans’ love affair with automobiles, the car was both technology and media, affecting how people perceived and understood the surrounding world: It charted territory, shaped physical and social landscapes, and “refashioned all of the spaces that unite and separate men.”16 The postwar Jeep, with its redesigned driver-passenger setting and associated hierarchy, not only catered to new owners and usages but also established visible boundaries between owner-passengers, drivers, and those who could not afford such a vehicle (see Figure 3.2). For being not only expensive, but also difficult to acquire, it was an elite vehicle in China that displayed wealth and power.

Figure 3.2 “The Jeep becomes a general-purpose vehicle,” 1946. Min jian.

As technological elements enhanced the Jeep’s prestige and allure, its arrival became a cultural event in Chinese society. More than just a military vehicle, the Jeep was a spectacle to behold. In the wake of liberation in August 1945, thousands gathered outside the Park Hotel in Shanghai to catch a glimpse of the first Jeep brought into the city by the United States Military Advisory Group. Newspapers recorded the “crazy scene” where “all day long the rubberneckers milled around and crowded the site,” and some even climbed onto the vehicle. Despite not speaking each other’s language, according to one report, the onlookers and GI drivers smiled at each other and shook hands.17 Apparently, even residents of the most cosmopolitan city in China could not resist the charm of the Jeep and looked like country bumpkins in front of this newfangled product. Dance stars and movie celebrities posed with Jeeps in photos, and their joyrides in public were reported by local tabloids. Children were also invited to experience this new vehicle. One local publication enthusiastically announced: “Kids! Now you also have an opportunity to ride in a Jeep.”18 Another article taught them how to craft a paper Jeep toy, complete with detailed instructions for cutting and coloring.19 A twelve-year-old boy’s paper Jeep was featured in a magazine alongside a horseracing scene, Christmas tree, wooden rabbit, and goldfish – a mixture of global novelties and Chinese tradition – all to “inspire the minds and intelligence” of children.20

Even the Communists, outspoken critics of US military assistance to the Nationalists, were captivated by the Jeep. In the summer of 1944, the United States Army Observation Group, commonly known as the Dixie Mission, arrived in Yan’an to establish the first official relations with the CCP. Operating from July 1944 to March 1947, the Group made a memorable entrance by plane, bringing several Jeeps loaded with American goods as a replacement for local animal-drawn carts. Having a ride on a Jeep was a novel experience for most Chinese at the time, even more so for the few who could drive one. Decades later, a Communist Party member involved in hosting the mission described his first experience of learning to drive the American vehicle: “The Jeep car was like a frightened savage horse, running wild in a flying speed. I could only hear the sound of wind passing through my ears.”21 During his historic visit to Yan’an in March 1946, General Marshall, standing at the front of a Jeep with Mao at the rear, greeted the crowds at the airport, who cheered and displayed welcoming signs celebrating Sino-American friendship and collaboration. After the Group’s departure in 1947, the Americans left these Jeeps to the Communists – together with portable radios, electricity generators, and telegram equipment – and they were immediately put to good use in the civil war.22

At the center of the Jeep’s enchantment was speed. On the paved roads of modern cities, the motor vehicle’s engine provided passengers with fast transportation over long distances. Like the aforementioned Communist driver, when describing Jeeps, Chinese observers almost always used expressions such as “wind-like speed” and “wild run.” Speed was the pleasure invented by modernity: The experience of speed became the quintessential way for a person to experience modernity in an age of mass production, a type of “adrenaline aesthetics.” Speed also changed concepts of space, distance, chance, and violence.23 By the 1940s, America, as the industrial powerhouse of the world, had already become a creature of four wheels. Associated with speed, the car symbolized and materialized new freedom, individuality, and agency. In Republican China, city residents had also been trained to see, hear, sense, and admire speed through cinema, advertisements, and fiction. Speed, in the words of New Sensation School writers, was a novel experience that was dangerously exuberating and had permeated the modern Chinese sensorium.24 If the Chinese awe and fear of the train were more closely linked to the nation-building and colonial expansion of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, focusing on the locomotive’s massive power and spheres of influence, the Jeep automobile provided a more independent, flexible, and individualist experience at a fast and controllable speed for travel and transgression, a different type of modern thrill.25 The Jeep could turn, reverse, and stop whenever and wherever it wanted, projecting an imagined individual self with free will.

The charm of a speedy Jeep also involved intimacy and romance. One college student’s “deep friendship” with an American officer began with a Jeep ride. A married, middle-class woman danced happily with her GI boyfriend late into the night, while a Jeep stood by, ready to whisk her home quickly and safely.26 Visual depictions often highlighted the flying hair or attire of “Jeep girls,” who received the title from riding in American military vehicles during the war.27 In one cartoon titled “Jeep Rhapsody,” a GI first drives the Jeep along a steep flight of stairs, picks up a girl who has waved to him seconds before from her window, then drives out of her window in the now-flying Jeep with clouds underneath (see Figure 3.3).28 Another critic mocked the “Jeep car and Jeep girl” as “the smell of gasoline mixed with face powder scents … creating an exotic atmosphere.”29 Representations of a GI driving a Jeep in China were highly masculine and often sexual, as the vehicle either carried women or was used to lure them.

Figure 3.3 “Jeep rhapsody,” October 1945. Zonghe zhoukan.

Figure 3.3Long description

He then drives up a steep flight of stairs and drives out of her window in the now-flying Jeep, with clouds underneath and the girl seated beside him.

The experience of speed and automobility intersected with modern explorations of subjectivity, sexuality, and affect. The typical scene in a Chinese narrative of the GI Jeep began with the sight of a moving vehicle, followed by a view of the foreign driver behind the windshield and a provocatively dressed Chinese woman sitting next to him on their way to restaurants, clubs, and hotels. In the speeding moment, the air would be filled with laughter, smells of perfume and alcohol, and the flaunting girl’s evident pity for those less fortunate. It was a multilayered experience featuring the thrill of speed and the danger of transgression in geography, intimacy, and sovereignty. As such, the Jeep was both a material and a cultural object, a manifestation of military, industrial, technological, and cultural power.

The postwar Jeep symbolized a transformative techno-modernity, an American style with supreme speed, mobility, versatility, and commercialization brought about by the liberation. The expanding repertoire of Jeep neologisms such as “Jeep car” (jipu ka), “Jeep soldier” (jipu bing), and “Jeep girl” (jipu nülang) further revealed a type of modern hybridity shaped by sociocultural imaginings of the other. By cleverly playing with a pun on the Chinese character ji 吉, meaning good fortune, Jeep (jipu) acquired auspicious connotations.30 In its early phase, Jeep conveyed favorable capital that was extended and transferred to other commodities, objects, and endeavors. For example, a new cigarette brand was named “Jeep Car,” and the Jeep also functioned as a prominent prop in advertisements for other commodities symbolizing wealth, power, and status.31 Even a leftist journal adopted the neologism as its title, stating that although it had nothing to do with the vehicle, the journal meant to convey “people’s opinions” (minyi), based on the meaning of “general purpose,” which many attributed as the origin of the word “Jeep.”32 This prestige and glory associated with the Jeep, however, remained short-lived.

Dangerous Roads: Traffic Accidents and the New Machine Monster

Jeeps rampaged on the land of China. People became ghosts under their wheels, nowhere to appeal … Let’s learn from our senpai Ah Q’s spirit, as if it was still during the war, as if the Jeeps could race even faster, and the innocent drivers could have two more glasses of champagne.

A moving Jeep did not always deliver chocolate, gum, or good fortune – at times, it brought serious accidents. In the wake of the GIs’ arrival, traffic accidents became the most common, frequent, and visible form of their misconduct in Chinese cities. American drivers, often drunk or recklessly speeding, injured and killed the elderly, children, women, and other passengers or pedestrians. A glance through local newspapers of the time reveals countless reports of these tragedies. On December 16, 1945, a fast-moving American military vehicle in Shanghai knocked four pedestrians to the ground, injuring three of them, together with another pedicab rider.34 On August 16, 1946, a Jeep killed a six-year-old on the sidewalk before driving away. When a young Shanghainese jumped onto the Jeep to stop it, he was hit by the driver and fell out.35 On November 4, 1946, in Tianjin, a speeding Jeep hit a pedestrian, who died from severe brain injury before reaching the hospital; the Jeep disappeared.36 Two days later, a marine Jeep crashed into another local pedestrian, who succumbed to severe injuries shortly thereafter.37 On October 16, 1947, a military Jeep in Shanghai crushed two pedestrians to death while injuring a woman, right in front of the headquarters of the Three People’s Principles Youth Corps, the Nationalist Party’s youth organization.38

Traffic accidents involving Jeeps had become a familiar experience for residents who saw, heard, or read about them, leaving a long paper trail in the records of local police departments and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. According to a police report by the Shanghai municipal government, for example, an estimated 495 traffic accidents involving American military vehicles occurred in the city from September 12, 1945, to January 10, 1946, resulting in 18 deaths and an additional 218 injuries.39 Even American reporters observed victims of GIs lying in Shanghai hospitals soon after the troops’ arrival.40 It almost felt as if Chinese city streets had turned into another dangerous war zone, where walkers, passengers, rickshaw pullers, pedicab drivers, and even on-duty traffic police frequently fell victim to US military vehicles.

In Chinese critiques, “Uncle Sam’s children” and the new automobile were often presented as one and the same: The Jeep was the personified American soldier and the GI was the Jeep in motion; both were masculine, foreign, and dangerous. Jeeps and GIs were blamed for each other’s wrongdoings and became an inseparable criminal duo that claimed the lives of innocent pedestrians, bullied rickshaw pullers, and chased and assaulted virtuous young women or carried indecent women around. The Jeep-GI marched without boundaries or restraints, intimidated others with his endless power, and then boasted of his conquests and possessions. In fact, the Jeep-GI duality existed from the time the Jeep was invented. A widely held belief suggests that the name “Jeep” originated from its connection to the GI.41 More than a versatile and enduring machine, the Jeep was also a loyal comrade on the battlefield, providing assistance, protection, and companionship. In 1943, General MacArthur, who commanded the Southwest Pacific Theater, awarded a wounded Jeep, “the old faithful,” a Purple Heart to honor its service in WWII. The Jeep was “an impersonalized common American soldier,” newly introduced, going through rigid boot camps, and finally gaining confidence in war, embodying the soldier’s three key ideal traits: optimism, comradeship, and loyalty. Representing the signature spirit of rugged and practical individualism, the Jeep was promoted as an American symbol, burnishing the myth of the iconic figure.42 In the postwar world, the Jeep quickly became a successful civilian model within the United States and was exported abroad with great success, extending its legendary wartime career.

China first seemed like another remote land where the American hero forged new tales. The vehicle’s wartime reputation and surrounding myths greatly enhanced its early appeal. Yet as frequent traffic accidents occurred and news of these spread, the Jeep became a new villain in disguise as a war hero gone wild. After the initial curiosity and excitement, the Chinese populace was struck by the risk, danger, and failure of its technology and its human agents. The accident was a negative indicator, not only of human flaws or negligence, but also of technological failure: The vehicle threw people out on a sharp turn or in a bad collision and failed to stop in front of a playing child. The higher the speed, the greater the severity of the accidents and the lack of control. Earlier expressions of modern thrills about speed, sensation, and freedom were already mixed with a fear of chaos. In fact, Chinese perceptions of the Jeep featured a curious ambivalence from the beginning, even among enthusiastic consumers of foreign goods and experiences. The Jeep journey was felt to be uncannily easy, fast, and full of thrills and excitement, much like flying. At the same time, the journey entailed a sense of violence and potential destruction. In cartoons, “Jeep girls” often looked both thrilled and alarmed, fearful of the rampage the vehicle caused on the street, dreading the impending or potential damage and self-destruction. The supreme qualities of the Jeep were accompanied by an ever-present fear of danger.

A moving vehicle meant a living man. Yet the Jeep was more than an ordinary human: It ran amok on the street, breaking every rule and terrifying all. Ultimately, the Jeep/GI became an abhorrent foreign military monster that was part human, part machine, part beast. The GI in the Jeep was more than a “red-haired foreign devil,” a phrase that the Chinese traditionally used to describe Westerners out of racial and cultural fear; the GI in the Jeep was a “killing tiger” with giant headlights, shining with animal urges and wild intimidation.43 This was an ominously different type of monster, one with a machine shield and armor.44 In a way, the Jeep was a mechanical extension of and addition to a GI’s physical body. It allowed him to penetrate into territories that had previously been difficult or impossible to reach, at a new speed and with actual protection and a sense of invulnerability. It enhanced his claims of masculinity and his allure with the thrills of speed and mobility. In the glimpse of motion, the boundary between human and machine became blurred; the Jeep/GI appeared as a technologically enhanced, foreign military beast that could not be tamed and that transgressed proper geographical, cultural, national, and racial boundaries. The Jeep provided speed, mobility, versatility, and physical protection. It was essentially a human enhancement, an embodiment of the massive militarization of technology and high industrialism of the United States. Consequently, the GI transformed into a mechanically enhanced soldier and hypermasculine alien man with supreme technology, strong purchasing power, and insuppressible sexual drives – a hypersexualized body with uncontrollable animal urges.

Reflecting this technologically mediated fear, Chinese media increasingly depicted GI driving as reckless, impudent, or even brutal. A children’s magazine recounted a tragic incident when a Jeep struck a child playing on a street in Nanjing, resulting in a broken leg, significant bleeding, and death.45 Another reporter rushed to an accident scene just steps from the iconic Sun Yat-sen bronze statue that stood at the capital’s heart. There, an overturned Jeep and three blood-covered, intoxicated GIs presented a grim spectacle. Writing with a mix of rage and mockery, the reporter described his excitement at witnessing the scene as akin to watching a Japanese plane being shot down, dubbing the Jeep a “big coffin” for the Chinese.46 In an almost complete irony, Chinese now painted the Jeep as “disorderly, rude, outrageous, and dangerous,” the exact opposite of the “self-sacrificing, humble, homely, but willing to get the job done” entity of its creation myth. The common American boy had become an oversexualized and indecent GI. This growing grievance against GI driving solidified into a shared sentiment and concern. Even The China Weekly Review, the prestigious first English periodical founded by American newsmen, published Chinese readers’ protests. Charles Tsao, a student of St. John’s University, China’s leading American missionary college in Shanghai, wrote to the editor on September 25, 1946, of the “nuisance of the shameful servicemen of the U.S. Army and Navy” who were killing innocent Chinese every day in Jeep accidents while the American generals explained to the press that “the GI’s life is too monotonous.” Declaring himself “not a narrow-minded nationalist,” and speaking “from a Christian standpoint,” Tsao asked: “My Lord, do you Americans kill your fellow citizens for fun in the States?”47 Another reader, “Lone-Portia,” recounted an incident near the American consulate in Chongqing on December 7, 1948, when a ragged little girl “was crushed by a jeep car of military police and had uttered her last cry for help” while the “criminal chauffeur had driven away” and “the constable there paid no attention.” The young woman cried: “It is not in this world that Heaven’s justice ends.”48

The Chinese anger over Jeep accidents was understandable, and the fear real. Many of these most sensationalized accounts came from the Communist media, which targeted reckless GI driving in their anti-American campaigns. But this was an easy fight to pick. The CCP seized on the rising tensions, politicizing these incidents to condemn the so-called American brutalities and the Nationalist Government’s incompetency and betrayal. As the GI presence became more visible and accidents more frequent, it was easy to frame the situation in the language of American imperialism. And indeed, drunken drivers often fled accident scenes or denied any responsibility. For the few who were caught or identified, legal consequences were minimal or entirely absent. This lack of accountability further inflamed public outrage and led to a shifting perspective on the Jeep. Patriotic students, leftists, and even some pro-American liberals increasingly came to see the Jeep as a symbol of foreign domination: GIs driving this foreign vehicle, which killed citizens on their own soil with no repercussions, represented America’s trampling of Chinese sovereignty.

Overall, the Chinese experience of the Jeep was one of dangerous thrill mixed with techno-political fear. The Jeep was a material and cultural manifestation of the new American global empire. Since the nineteenth century, new infrastructure and transportation technologies, such as paved roads, railroads, telegraphs, and telephones, had facilitated American expansion. After WWII, the United States extended its unprecedented territorial influence afar and asserted power over diverse populations through its supreme techno-political capabilities and universalist claims to its values.49 To Americans, the wartime “military Jeep” turned into the new postwar “Universal Jeep,” a new-day vehicle designed for peace that would serve mankind around the world. In the eyes of many Chinese, however, Jeeps took over their streets and penetrated deep into the very center of city life. They appeared unbounded, parking outside of dance halls, hotels, cafes, shops, and movie theaters in downtown alleys, and even encroaching upon sacred spaces such as the Imperial Palace and the Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum. Jeeps harassed innocent women on the street, abducting victims of sexual violence and fleeing crime scenes effortlessly with no trace or consequence. As such, the Jeep became the ultimate metaphor for the masculine American military empire in an age of high industrialism and global hegemony.

Global Speed in Local Terrains: Street Politics

When American global speed met the intricate local terrain, frequent traffic accidents showcased the complex political, social, and cultural clashes between GIs and Chinese society at large. Speed was a thorny issue that needed government intervention through the use of traffic lights, speed limits, police, new rules, and the arbitration of responsibility. To accommodate the American vehicle system, the Chinese government issued new traffic regulations and right-side driving rules at the end of 1945, replacing the existing left-side driving system.50 At the instigation of the American military, traffic shifted to the right side of the street on January 1, 1946 – marking another way the American presence reshaped the postwar Chinese landscape.51 Critics lamented that China had abandoned a fifty-year-old practice overnight, just for the Jeep.52 Meanwhile, new speed limits were set, partly in response to a rise in accidents caused by speeding American vehicles. In Shanghai, for instance, speed limits of twenty and thirty kilometers per hour in the city and suburban districts, respectively, were established for all vehicles.

Chinese cities of the 1940s were at once modern metropolises and uncharted backwaters with narrow, curvy streets, few traffic lights, unobserved rules, and premodern modes of transportation jostling for space. Urban roads, with their busy traffic and not always law-abiding citizens, presented a new challenge for GIs, who were used to broad country roads back home or battlefields in the Pacific, where they drove at fast speeds and in open spaces. Many were overwhelmed and bewildered by the dense and confusing Chinese urban space, from the maze of paved and unpaved roads in Beijing to the winding streets of Qingdao and the tight alleyway neighborhoods of Shanghai, all lacking adequate traffic signs and policing. On these busy streets, American military vehicles were sharing and often competing for the same space, not only with other motorized vehicles, but also with rickshaws, pedicabs, bicycles, wheelbarrows, mules, and horse-drawn carts, a chaotic mixture of premodern and modern transportation types. In a playful irony, the Chinese word for a modern road, ma lu, literally means “horse road.” The majority of the local population still lived in rural areas in the 1940s and were unused to motor vehicles. The new speed was said to be so alien that they were “totally unable to calculate the speed with which trucks and buses move,” and thus failed to “realize the danger of being struck by such [a] vehicle.” Visitors to China reported seeing instances “where villagers or farmers, riding for the first time on a truck, simply jump off when they reach their destination without waiting for it to stop. They have not learned to comprehend the speed of such vehicles, having been accustomed throughout their lives to nothing speedier than a buffalo or a bicycle.”53 For many Chinese on the street, encounters with the Jeep and the American military began as an uncanny bodily and sensory experience.

If the Americans often drove speedily, took sharp turns, and parked freely, it is fair to say that failure to follow the traffic rules was common among all those sharing the roads at the time. Shanghai traffic was a mess in 1946, what some called the worst in history. The situation remained chaotic even after the Communist takeover in 1949, “since pedestrians, automobile drivers, and pedicab men all use the streets as if they belonged to them personally, with virtually no regard for anyone else.”54 In short, everyone behaved badly on the streets and no one followed the rules, nor were the rules strictly enforced. Critics commonly attributed the mess to “overpopulation of this metropolis in the wake of peace, bringing with it [the] greatest volume of motorized, man-propelled and pedestrian traffic in the city’s history,”55 as well as a “host of offenders – jaywalking pedestrians, bicyclists, ricksha runners, pedicab pushers, horse carriages and motor car and truck drivers.”56 Others pointed fingers at the local police. One called them “the root of the evil” for only enforcing the rules sporadically and merely for show.57 Another blamed the existing chaos on the “lackadaisical” and inefficient traffic police, some newly added to the Shanghai police force, completely unaware of the rules or simply not enforcing them.58 When WWII ended, for the first time since the mid nineteenth century, Shanghai came under a unified Chinese government. Now with heightened nationalist pride and a strong desire to abolish extraterritoriality, the new government faced the challenge of creating a new system to replace those in former foreign concessions while governing a cosmopolitan city filled with a massive influx of groups from the southwest, refugees looking for jobs, and Allied soldiers.

Compared to the elite class who tended to criticize government control and actions, civilian victims were more focused on restitution issues. After serious traffic incidents that resulted in injuries and deaths, the Chinese usually appealed for compensation through local governments, who then transferred the requests to the US authorities in China. Failure to fulfill such requests became a leading source of tension and disputes, centering around two core issues: Who was responsible and what would be the proper compensation? While Chinese usually blamed American negligence or disregard of their lives, GIs attributed accidents to locals’ complete disregard of rules. In reality, there was a range of causes of accidents, and it was sometimes difficult for the US military authorities to come to an easy solution; in extreme cases, the desperate poor tossed babies under US trucks, hoping for compensation.59 But in general, GIs believed that most accidents happened because “Chinese pedestrians and cyclists exhibit great carelessness in their attitude toward the movement of motor vehicles.” American soldiers and MPs frequently expressed frustration with Chinese not following any rules, ignoring traffic lights and not using crosswalks, or rickshaws not staying in the same lane. As one marine observed, “pedestrians did not feel compelled to restrict their movement to the sidewalks, by any means.”60 In response, the US military made persistent requests for new traffic lights, signs posted at major intersections, and strict police enforcement of traffic rules.61 But the Americans did not always adhere to the regulations themselves. On January 7, 1946, a few days after the implementation of the new speed limit in Shanghai, Lieutenant Colonel Sylvio L. Bousquin complained to the mayor that numerous Chinese civilian cars were exceeding the newly established speed limit. This, he argued, made it difficult to justify enforcing the speed limit on American military vehicles. Bousquin deemed the enforcement discriminatory, calling “the singular emphasis placed upon American military vehicles and personnel unfair and unjust.”62

The American perspective on the problems affected the compensation system. In practice, the policy was said to be quite liberal. The payment that deceased victims’ families received ranged from more than a thousand US dollars to zero, depending on whether such claims were deemed meritorious, partially so, or not at all. Occasionally, individual soldiers involved also paid out of their own pockets when such requests were denied by the US claims office.63 To “standardize the practice,” the US Navy issued “instructions to drivers” in case of injury to a person or damage to property, as follows: “a. stop car immediately and render such assistance as may be needed. b. fill out form, on the spot, as far as possible. c. deliver this form properly to your immediate supervisor.” American soldiers were advised to wait on site for MPs, rather than talk to locals or privately settle claims that involved the liability of the US government.64 Overall, while “evidence” was considered crucial in the decision-making, Chinese testimonies were often overlooked or dismissed as nonessential or unreliable within the American justice system. Lack of evidence and procedural issues were commonly cited as reasons for exonerating the accused, even when Chinese witnesses were abundant, leading to a “Chinaman’s chance.” In accidents where GIs were not deemed “contributing factors,” local victims would be denied compensation by US military authorities, given the standard justification that “the claimant failed to exercise a reasonable amount of caution.”

The American decisions and rationales were, however, unacceptable in Chinese eyes, for they often held different ideas about who had the right of way and who was responsible when traffic accidents occurred. Generally speaking, the Chinese customarily held automobile drivers culpable under all circumstances, regardless of whether or not the pedestrians had checked for traffic before crossing the road; this was partly due to an ongoing traditional belief that those in power bore more responsibility because of their advantageous position. For instance, in the early phase of motorcars in the 1910s, some Chinese commentators argued that a carriage had the right of way over a motorcar because it was easier for the latter to make a full stop than for the animal. In 1949, after US military vehicles disappeared from the newly captured Chinese streets, the general rule was established that the drivers of motor vehicles were responsible for accidents that occurred to pedestrians and cyclists because rural populations had little experience with motor vehicles and were unaccustomed to their speed.65 Even today, the disorder on China’s roads can be partially attributed to the belief that drivers, equipped with more powerful machines, bear a greater responsibility compared to pedestrians, regardless of whether the latter are breaking traffic rules. Such a mentality and rationale were in sharp contrast with the modern American notion of equal responsibility based on whether or not one follows the rules. Further, the traffic conditions and systems of the two countries were quite different, with China having adopted European road directions. Motor vehicles were still rare in rural areas. Most hawkers, rickshaw pullers, and other coolies had little knowledge of speed limits or the right of way. Similarly, urban pedestrians were not used to using crosswalks, even when they were available.

The numerous petition letters sent to municipal governments further revealed a major gap between the legal and sociocultural understandings of these incidents among Chinese civilians, some of which were also shared by local officials, and those held by the American military. In local petitions, the pursuit of justice was intricately linked to seeking reparations. For the injured survivors and victims’ families, predominately from the laboring class, the first and foremost request was recompense. This monetary relief was usually requested based on the cost of medical treatment, funeral expenses, and loss of income to support their families. For instance, after the death of Zhao Xueyao – an eighteen-year-old worker at a Tianjin textile factory who was fatally struck by an American military truck while his bike was crossing an intersection on the night of July 18, 1947 – his brother submitted a plea to the mayor of Tianjin. This appeal was crafted in the standard format used for such letters. It read:

I respectfully petition Your Honor on behalf of my younger brother, Zhao Xueyao, who was tragically killed by an American military vehicle. I implore you to negotiate compensation on our behalf to alleviate our suffering. My parents are elderly and have no means of income, and I am unemployed. Our family, which includes nine members, both elderly and children, relied on my younger brother to survive … Since his untimely death, we have been plunged into poverty, unable to secure even loans. As winter approaches, we face severe hunger and cold, and fear that we may succumb to starvation.66

Traditionally, financial compensation was considered a just and legitimate means of achieving justice. Material redress was an integral part of seeking moral and legal justice, especially for the impoverished. For many victims at the time, it was even a necessity, as the male victims tended to be the only adult laborers working in cities and providing for their families back in the countryside. Family situations, such as having young children and elderly parents, as well as the lost wages of the dead, were usually mentioned in appeal letters to justify their requests. To those involved in these traffic incidents and the observers reading about them, the denial of compensation meant economic devastation to poor victims’ families, especially if they lost the only breadwinner.

Invoking a Confucian style of paternalist relations, these letters appealed to benevolent local officials for justice and mercy. Victims were often supported by a network of intermediaries that included hometown organizations, professional associations, and family members who were literate and had more sociopolitical resources. Typically, these petitions began with polite pleas highlighting personal tragedies, then shifted to sharp critiques of GI criminality if initial requests went unaddressed.67 To make their case, the petitioners often linked the GIs’ misconduct and the victims’ failure to receive proper compensation to broader issues of national equality. Instead of citing specific traffic laws or legislations, these appeals stressed the political problem of the US military presence in China and highlighted GIs’ contempt for the Chinese people. They criticized the US military’s procedures and rationales for denial of compensation as unsatisfactory and its dealings as subjective. Moreover, the dismissive responses from American officials – often a terse, standardized letter – coupled with the lack of repentance evidenced by repeat offenses, was condemned as an affront to the national dignity of all.

The intricate street politics of the Jeep in China was a microcosm of the complex Sino-US interactions on grassroots levels. Influenced by national and racial inequality, these everyday struggles involved various factors including negligence, prejudice, misunderstanding, and differences in technological, social, political, legal, and moral systems. In response to rampant traffic accidents involving American military vehicles, local governments sometimes took actions on their own. For example, the Shanghai Police Bureau once issued orders to fire at such vehicles in “extremely grave” situations.68 However, the Nationalist Government as a whole lacked the practical and legal means to handle these issues. It struggled to reconcile Confucian moral legitimacy with the American legal system, which relied on trial systems, witness testimonies, and proof of evidence. Hindered by extraterritoriality, the Nationalist Government did not possess judicial authority over the accused GIs. The limitation undermined the government’s credibility when it failed to secure redress, settle disputes, and provide justice for victims. This pattern of disputes over responsibility and compensation was evident in various street incidents involving Chinese civilians, ranging from traffic accidents to deadly violence against rickshaw men, which became a more prominent headline issue.

Friends and Foes: GIs and Rickshaw Men

On January 24, 1946, Pulitzer Prize–winning author John Hersey wrote from Shanghai, detailing GIs’ rowdyism in the city, ranging from deadly traffic accidents caused by drunk drivers to MPs slapping coolies. Born in Tianjin to an American missionary family, Hersey had learned to speak Chinese before mastering English and spent the war years reporting on conflicts in the Pacific and Europe. In his “Letter from Shanghai” for The New Yorker, he observed that “Jeep diplomacy” was replacing “Dollar diplomacy,” referring to the large number of Jeeps crowding the streets from US surplus aid and sales.69 One particular social group affected by this Jeep diplomacy was the Chinese rickshaw pullers, who faced multifaceted impacts. While the Jeep taxi became a competitor and threat to the declining business of the rickshaw, pullers also found themselves beneficiaries of GI patronage, with many servicemen routinely using the service while on liberty. At the same time, rickshaw men were among the first and most frequent casualties in the street accidents caused by American military vehicles, as the two shared the undivided lanes and competed, often aggressively, for the right of way. Overall, the actual and symbolic interactions between American soldiers and Chinese rickshaw men, a relationship that mingled fantasy, patronage, rivalry, and conflict, represented the most entangled type of Sino-US relations.

In the newly liberated Orient, American soldiers encountered the labyrinth of Chinese urban life with its social hierarchy and long-existing rickshaw empire, which was in the final phase of its existence. For Chinese society, the rickshaw trade had been controversial for decades. Invented in Japan in the late 1860s, rickshaws (ricksha, jinrickshaw) quickly appeared on Chinese city streets, and rickshaw pulling had since become a major type of work for laborers. The rickshaw was also called the “foreign vehicle” (yang che) in China because of its technological advances during the time of its introduction and its early association with the modern paved roads of city life. After the technological improvements of a lighter frame and rubber tires in the early twentieth century, which increased both comfort levels and speed, the popularity of the rickshaw rose among city dwellers. The rickshaw had become a new and often superior form of transportation compared to the old sedan chair and walking. In 1946, more than fifty thousand pullers and twenty thousand rickshaws were running on the road of Shanghai.70 In 1947, there were more than ten thousand rickshaw pullers, 227 rickshaw companies, and more than seven thousand registered rickshaws in Nanjing.71 Most rickshaw men were rural immigrants to the cities who survived on daily hard labor.

The rickshaw man had occupied a central place in Republican cityscapes and public discussions from the very beginning.72 Liberals, social reformers, and socialists had long criticized the business for its inhumane treatment of labor. During the New Life Movement, the Nationalist Government attempted to ban or reduce the number of rickshaws, fearing such “inhumane” labor would tarnish China’s international reputation as a modern nation. Meanwhile, the industry had been facing increasing competition from trams and motor vehicles. The postwar government continued its earlier unsuccessful campaigns to abolish the rickshaw trade, beginning in 1945 to reissue regulations aiming to gradually reduce and eliminate rickshaws over a three-year period. In 1946, the Executive Yuan issued implementation edicts across the country. However, the rickshaw pullers, as before, strongly opposed the ban and organized collective actions, including a vow to engage in street riots.73 Concerns about the ban’s impact on labor welfare were also raised by some reformers, who warned that the former rickshaw pullers might try to beg, steal, rob, or kill instead. The situation escalated in late September after the death of a Shanghai puller named Zang Yaocheng (Tsang Ta Erh Tsu), who was killed by an American sailor.74 This incident, which will be discussed in more detail later in this chapter, sparked large protests in the city. In response, the Nationalist Government set out to reduce the number of rickshaws and street peddlers “to promote morality and improve traffic conditions.” Nevertheless, critics called the ban motivated by “a desire to please the Americans who thought rickshaw pulling degraded humanity,” and warned that as a result of the ban, “100,000 rickshaw pullers and their dependents would be deprived of a livelihood in due time.”75 Another critic in Beijing pointed out that the postwar ban was mostly because America did not have the rickshaw.76

The influx of American personnel unfamiliar with local roads and landscapes injected some fresh blood into the declining business. Rickshaw men offered convenient and necessary transportation for these foreign soldiers eager to explore local attractions including scenic spots, restaurants, clubs, theaters, registered and underground brothels, and other places of entertainment. More than mere transporters, pullers traditionally also assumed the role of local guides for outsiders, offering inside knowledge of the hidden nooks and crannies that did not show up in the usual guidebooks. Some pullers even leveraged their roles to act as intermediaries, earning commissions from brothels. As such, American patronage became a vital new source of income for many of them. Ironically, the GI presence both reenergized a business in crisis and accelerated its final diminishment. The flood of American motor vehicles, especially Jeeps, contributed to the steady decrease in the number of registered rickshaws in Shanghai, which went from 23,066 in March 1947 to 11,029 in August 1948.77 In response, rickshaw pullers’ associations protested the government’s ban and distribution of Jeeps to the taxi association. They argued that it would lead to the elimination of rickshaws and the loss of the pullers’ livelihood.78

For the Chinese government, the rickshaw was a backward social institution and practice to be abolished, for it had no place in the new, modern, and now victorious nation. American views toward the rickshaw, however, were mixed. It was a useful or necessary transportation; in one cartoon, a marine driving a Jeep on a flooded street watches with frustration and jealousy as another GI in a rickshaw rides by, staying dry, comfortable, and smoking in leisure.79 Despite the occasional comical celebration, most comments from GIs’ memoirs emphasized pullers’ skinny bodies, harsh labor, poverty, and what they saw as human beasts of burden. Even to more sympathetic eyes, “the average farm mule in Alabama had a far easier life than a Chinese rickshaw coolie.”80 As four-wheeled industrialization democratized road usage among Americans and reshaped their urban landscape and social relations, GIs found in rickshaw men the very embodiment of an inferior civilization of the Orient.

Racism was inherent in GI perceptions of Chinese rickshaw pullers and structured their daily interactions. Being pulled by another human being was an exotic experience, a must-have on the Oriental menu for a GI tour. Pictures of and with pullers were among the most popular China souvenirs sent home. Fueled by “the combination of the troops’ high spirits and the Chinese alcoholic spirits,” American soldiers also raced each other by pulling rickshaw men down the street, causing expressions of “abject terror on the faces of the ricksha runners as they held tightly to their precarious perches in the passenger seats.”81 This act of apparent role reversal, presumably amusing to the GIs and their audiences back home, had deep roots in racism. Similar to white performers in blackface in American minstrel shows, who performed eccentric “black” songs and dances, this role reversal was a mockery and conveyed to the audience mixed feelings of fascination, desire, and fear.82 It lampooned Chinese society and culture as exotic and backward for still treating humans as animals while reinforcing notions of white superiority. More broadly, the rickshaw experience validated existing racial and national hierarchies both inside and outside the United States, as in the use of “colored” porters in Pullman train cars. As a Chinese critic noted, the sight of American soldiers pulling rickshaw men was not merely a comedy or a joke because, “unfortunately, we ourselves are the characters in this comedy, or objects of mockery.”83

Besides routine rides, the enlisted men invented “some spectacular amusements” involving the rickshaw, in Hersey’s words, to “take their exuberance out on the town.” An official Stars and Stripes rickshaw derby was held in Shanghai on December 1, 1945, in which nineteen “jockeys,” girls from the Allied forces, were pulled by Chinese coolies “known as ‘horses’” (see Figure 3.4). This event attracted ten thousand GI spectators who gathered at the destination of a stadium originally built for greyhound racing in the former French Concession. Amidst their cheering roar, number seventeen puller, Jiang Ermao, finished the four-mile race first with a twenty-minute ride. The winning jockey was crowned “Rickshaw Queen” by General Wedemeyer, the commander of the American forces in China, and “the winning horse was given a floral horseshoe” and a prize of about seven American dollars.84 As the smiling Rickshaw Queen held her trophy facing the camera, Jiang stood beside her and “looked strangely at the garland of flowers placed around his neck, like a horse that had won the derby … His face exhibited curiosity framed with a cross between a smile and dismay.”85 While Chinese media criticized the implicit dog/horse analogy, a few months later, the winning rickshaw man was reportedly invited by the chairman of Madison Square Garden to compete with a famous American runner in New York City. The invitation was supposedly a result of the enthusiastic response to this GI creation, leading to the proposal of a Sino-US sporting event designed to recreate the spectacle to thrill audiences back home. However, it later emerged that the news was an April Fools’ Day prank orchestrated by American servicemen.86

Figure 3.4 United States Army Air Force officer riding in a rickshaw during a race in Shanghai, December 1945. NARA.

Figure 3.4Long description

The rickshaw coolie, a Chinese man, is wearing a shoulder sash that reads “HQ AAF.” A group of spectators has gathered under a canopy to watch the race.

Such entertainment events, supposedly for pure fun, went beyond simple cultural insensitivity and were instead rooted in the history of colonial hierarchy. The Western world had long associated rickshaws with the Other, particularly its inhumane, preindustrial usage of labor and animal-like behavior. The phrase “beasts of burden” frequently appeared in Westerners’ descriptions of Chinese laborers from the nineteenth century and was also commonly spotted in Allied newspapers. American soldiers rode rickshaws in Calcutta and in the Himalayas, where the interesting characters of Mongolian “rickshaw-wallahs” appeared to them as “rough-looking, likeable villains” because of their habit of “laughing and joking as they drag[ged] their unwieldy vehicles up and down Darjeeling’s steep and hilly roads.”87 In postwar Hong Kong, British sailors would take time off for races in rickshaws pulled by Chinese coolies while a shipmate acted as a traffic policeman.88 In South Africa, “Zulu rickshaw ‘boys’” who were considered “magnificent physical specimens” were said to “maintain an amazing pace with their vehicles” and to consider it “a special honour to carry a British serviceman, which they did with gay shouts and palpitating capers.”89 The rickshaw scene was in these ways so ingrained in the Western popular imagination of the Orient that children enacted such plays on the streets of London, pulling each other through the old Chinatown of the East End of the city, the Limehouse Causeway. This picture of old Chinatown captured “all the mystery of the glamorous East”: “The slant-eyed rickshaw boy pads silently through the burning streets – ‘Hold it, you dope, you’re off on the wrong tack! It’s the East all right, but the East End of London. And old Chinatown is Limehouse Causeway!’”90

The concept of China as a rickshaw-pulling nation was deeply embedded in the colonial discourse and Orientalist affects. The rickshaw and the Jeep represented contrasting forms of speed, power, race, culture, and civilization. Rickshaw queens and Jeep girls were the flip sides of this dualistic hierarchy. Just as American girls rode Chinese rickshaws for a leisurely outing or a fun race, Jeeps carried Chinese girls for GIs’ pleasure, to experience modern speed, entertainment, and adventure. Similar to how American tourists posed in staged opium dens in the alluring Chinatowns, taking home an apparent memento of white superiority, photographs of Chinese rickshaw men also helped confirm the superior values of democracy and equality that postwar America was proclaiming. As such, China became not only a nation newly liberated by white GIs from Japanese occupation, but also an Oriental country to be liberated from its own backwardness.

As in a typical colonial imaginary, American soldiers’ views of rickshaw men mixed fantasy of the exotic with fear of danger. They saw Chinese pullers both as exotic beasts of burden and as a distinctive sociological group that was “touchy and itching to quarrel” and requiring special talents to tame.91 Disputes over fares were a common trigger of conflict, with verbal arguments sometimes escalating to physical violence. With their salary and the low Chinese cost of living, marines could maintain comfortable lifestyles with servants, restaurant food, and luxury purchases, as well as a rickshaw ride that cost from three to fifteen American cents in Beijing.92 Most Americans were willing to pay extra for the novelty, comfort, convenience, or necessity of rickshaw rides. But some were more reluctant. While doing business, GIs found rickshaw men difficult to deal with, especially the endless bargaining. They complained about paying more than Chinese customers, sudden changes in predetermined prices, and frequent price increases by the collective group of pullers. Because of their unfamiliarity with local environments, confusion over the exchange rate, or experiences of dishonesty, they often felt taken advantage of, or even grew angry with pullers who persistently demanded fees, especially when alcohol was involved. When disputes with rickshaw pullers occurred, US servicemen on liberty without their guns sometimes felt vulnerable, outnumbered by huge crowds and overwhelmed by a mixture of verbal and physical aggressions. In designated parking areas and popular entertainment sites, pullers seemed to yell in unintelligible angry voices, determined to get what they were promised or deemed fair, and quickly resorted to their collective group power when tensions arose.

The rickshaw men had traditionally maintained a strong group identity for self-protection and competition with other groups. As one character in Lao She’s Rickshaw Boy explains, an individual rickshaw puller is like a grasshopper easily caught by a child, tied with a thread, and unable to fly. But when they come together as a group, they can devour an entire field of crops in a second, and there is nothing anyone can do about it.93 After the war, the pullers’ associations organized protests against the government’s plans to ban or reduce their numbers, as well as against owners’ attempts to raise rickshaw rents. They continued to clash with competitors such as city buses by damaging them in the streets.94 They also stood together when facing American soldiers, collectively raising fares and addressing disputes. Some pullers were connected to local gangs that solicited GIs into dubious businesses through a mix of lures and threats. On occasion, they openly insulted and assaulted GIs, even in the presence of local police, who themselves held grievances against these foreign soldiers.95

Overall, the American forces were confronted with a highly resilient and powerful group that was not easily swayed, as well as a problem that lacked clear macropolitical solutions (see Figure 3.5). After disputes, which sometimes became serious, the US military usually informed Chinese officials in protest, urging them to take actions, such as regulating fares and preventing cheating. Dissatisfied with the results of local intervention or lack thereof, the US authorities also tried to take matters into their own hands. In Qingdao, they designated some places “out of bounds” and considered prohibiting the use of rickshaws altogether. As they came to learn the organizational power of Chinese pullers, marine authorities proposed that “the U.S. Provost Marshal approach the president of the Rickshaw Pullers’ Association, warning him of the possibility of measures against the rickshaws and requiring him to make efforts to reduce ‘incidents’ against the Marines.”96 Another successful tactic solved the problem of inflated rickshaw ride prices for GIs in Beijing, perhaps temporarily, when an old China hand banned all rides until a better group rate was negotiated.97 But still much of the daily maneuvering was left in the hands of individuals, and how each dispute ended depended on individual circumstances and judgments, which were directly informed by their education, peer wisdom, and beliefs. In the eyes of many, conflicts with Chinese pedestrians, drivers, and rickshaw pullers were a clash of civilizations. They saw these civilians as cunning street mobs who tried to fool them with dishonest business practices, exploited their lack of local knowledge, and intimidated them into paying unfair rates for fares or huge compensation after accidents. Many enlisted men believed that an unarmed GI facing a dangerous coolie mob called for the use of strong force or even violence. Such perceptions were deeply shaped by America’s own history of racism and new experience of global occupation. These biased beliefs shed light on why rickshaw men often became victims of some of the most serious crimes and legal injustice.

Figure 3.5 American soldiers, along with local rickshaw pullers and pedicab men, gather around the scene of a traffic accident. MCHD.

Tale of the Everyman

At around 10:00 p.m. on September 22, 1946, Shanghai rickshaw man Zang Yaocheng pulled Julian Larrinaga, a Spanish sailor, from an American ship to a club, whereupon Larrinaga walked inside without paying. Zang waited outside until midnight, when Larrinaga finally came out with American sailor Edward Roderick after hours of drinking. Zang persistently requested his fare, and, surrounded by a group of pullers and pedicab riders during the dispute, Roderick hit Zang on the head, who then fell into a coma. Zang was diagnosed with a concussion and died at 5:00 a.m. the following day. After the incident, Zang’s only surviving child, a twelve-year-old girl, acted as the appellant, with her uncle serving as her guardian. Her letter, titled “American troops scorned the countrymen and killed my father,” was submitted to the mayor of Shanghai by members of the municipal representative council. In it, she requested compensation totaling 145,100,400 fabi yuan from the American side, equivalent to several thousand US dollars. The amount was calculated based on her father’s projected daily income from age forty-two until age sixty, and also included funeral expenses, the costs of her education and future wedding, and relief for the mental anguish she endured.98

In November 1946, a US Navy court-martial acquitted Roderick of the manslaughter charge and Zang’s family received no compensation. The decision resulted from a deep distrust of and legal discriminations against Chinese witnesses, especially rickshaw coolies, whose testimonies were deemed “unsatisfactory,” both “in establishing the identity of the accused and the offense of which he was accused.” An additional reason given was that “there was no American witnesses.”99 After the American decision on the Zang Yaocheng case, the Shanghai municipal government and the Chinese Foreign Ministry contended that the US government had failed to fulfill its obligations to ensure justice and had infringed on China’s sovereignty by taking a Chinese witness to its base for testimony without informing the Chinese authorities.100 On multiple occasions, the government tried to persuade the American navy to reopen Roderick’s case, arguing that it had failed to keep the Chinese side adequately informed, violating the terms of the jurisdiction agreement on handling criminal offenses committed by US service personnel. But these official inquiries and protests had no impact on the final legal decisions and did little to quell the anger of the Chinese people. Despite believing Roderick was guilty, Rear Admiral W. A. Kitts remained committed to “protecting what he saw as the established policy of his government, the interests of his service and, like most commanding officers, taking care of his man, even when guilty.”101

The Zang case was far from unique. Six months later, around 8:00 p.m. on March 30, 1947, a rickshaw puller named Su Mingcheng was killed by a US sailor in Qingdao in a similar situation. Petro Abarra, a US Navy steward’s mate second class, took a taxi ride to a “Prime Club” in downtown Qingdao. He refused to pay the agreed fare upon arrival and was ready to leave without solving the matter. Surrounded by his driver and several dozen rickshaw pullers waiting for customers at the site, Abarra took out a pocketknife and stabbed twenty-two-year-old Su Mingcheng in the thigh. Su managed to chase Abarra into the club before collapsing. Moments later, he was pronounced dead at the scene. Other pullers continued to pursue Abarra, who was finally caught by Chinese police officers after running several blocks. As in the Zang case, the offending soldier was taken from the scene by American MPs and later brought before a court-martial. The American court in Qingdao found Abarra guilty and sentenced him “to be reduced to the rating of steward’s mate third class, to be confined for a period of ten years, to be dishonorably discharged from the U.S. naval service and to suffer all the other accessories of said sentence.” The sentence, however, was reduced to five years confinement shortly afterward. Su’s mother was awarded US$1,500 as compensation for the death of her son.102

The two cases share striking similarities. Both incidents involved intoxicated soldiers who, late at night and during fare disputes, committed acts of violence against rickshaw pullers while surrounded by fuming, rock-throwing local crowds. In the aftermath, both victims were represented and assisted by rickshaw pullers’ unions, which petitioned the mayors for compensation from the Americans and demanded severe punishment for the sailors, an apology from US authorities, and assurances that such incidents would not reoccur. Leaders of rickshaw associations applied pressure on local labor affairs departments, warning that if their demands were not met, a strike involving “thousands of rickshaw pullers” would take place in “defiance of military curfew order and the [municipal officials’] plea to secure friendship between China and the United States.”103 These collective actions and negotiations reveal a strong social network that supported victims and their families in navigating the complex bureaucratic and legal systems. Local pullers’ associations, with a tradition of protesting against the killing of pullers by foreigners since the 1910s, played a crucial role in these efforts.

As it turned out, both incidents became political liabilities for the Nationalist Government, drawing protests from local rickshaw pullers, students, and other urban residents. Despite pressure from victims’ families, local associations, and the media, the government’s attempts to secure fairer sentencing and satisfactory compensation ultimately failed to wield actual influence. In contrast, the CCP quickly capitalized on these sentiments and launched extensive propaganda campaigns targeting these major cases. Coincidently, the Zang incident occurred just as the “US Troops Quit China Week” campaign was being launched in Shanghai, marking an early phase of the anti-American movement. Wenhui bao, a major Shanghai newspaper now run by underground CCP members, published more than forty reports on the Zang case from November 24, 1946, to April of the following year. Xinhua ribao, a Party organ, featured editorials with explicit titles such as “Protest against the Brutalities of the US Military in China” and “Heinous Murder of Zang Daerzi.”104 A lengthy biography with illustrations, including interviews of Zang’s brother and Chinese witnesses, was soon published in a magazine and later turned into a fifty-page pamphlet.105 Similarly, various Communist and leftist media outlets reported the brutal murder of the innocent young man Su Mingcheng. The tragedy left his elderly mother heartbroken and unconscious beside his cold, blood-covered body, adding another grievance to the US soldiers’ growing list of blood debts.106 Notably, these reports appealed directly to nationalist sentiments against American brutalities. Within them, Zang was portrayed as a Chinese everyman and “citizen of the Republic” (minguo gongmin).107 Su represented the urban poor laborer, “driven by hunger,” pulling a yelling American soldier “filled with brandy and whisky,” who was abusing, killing, raping, and setting fires” on the “soil of a semi-colonial country.” Su’s tragic death, deemed “worthless in the eyes of running dogs,” became a rallying cry that “united everyone with rage.”108 The Communist narrative transformed the rickshaw puller into a prototype Chinese victim, directly subjected to American violence and left unprotected by the corrupt, betraying Nationalist Government. This powerful image reduced the complex micropolitics and everyday struggles to a simplistic binary between brutal imperialists and defenseless victims, creating a unifying emotional appeal. As leftist broadsheets and CCP media closely followed the incidents, the two cases gained national prominence and later converged into the more vehement Anti-Brutality movement, which would soon shake the entire nation.

The Beijing Jeep

In May 1949, shortly after the People’s Liberation Army entered Shanghai, American Vice Consul William Olive was arrested on the street after forcing his way through two rickshaws that blocked his path. He was taken to a nearby police station, where he got into a fight with the police on duty and was subsequently beaten. As a result, Olive spent three days in a cell and was required to apologize in writing before his release.109 In the new China, the power of the proletariat, like the rickshaw man, triumphed over the power possessed by the American riding in a Jeep. As earlier modern experiences and desires associated with the Jeep faded into fragmented memories, the vehicle’s political symbolism as a foreign imperialist criminal became firmly established.

When the Jeep first came to the postwar Chinese streets, it was seen as a symbol of Allied victory, which then turned into a desirable cultural spectacle and popular commodity. But unlike in other places, in China, the vehicle did not smoothly transform into a sign of technology, progress, and, ultimately, postwar modernity.110 Instead, following frequent traffic accidents and GI crimes, the Jeep turned into a military tool of intimidation, danger, and harassment in the popular perception, a symbol of prolonged American occupation. The Jeep did not become a successfully domesticated commodity easily assimilated into Chinese culture, but remained a foreign machine driven by white soldiers, threatening the existing order of Chinese society and the nation.

While the last US military withdrew from China before the Communist victory and rickshaws finally came to an end in the 1950s, the American Jeep remained running on Chinese streets and subsequently had a long and interesting afterlife. As the Communist army defeated the Nationalists and captured their massive stock of American-made equipment, from weapons to vehicles, the Jeep became commonly used by the Communists in the civil war, and like the American and Nationalist generals, CCP officers also rode in Jeeps when commanding troops at the front lines. Perhaps there is no bigger irony than the “reunion” soon after. In the ensuing Korean War, these captured American military vehicles were again put to good use, this time in fighting the American imperialists directly in order to assist Koreans and protect the homeland. The domestication of the Jeep also took unexpected turns. After the Sino-Soviet split in the 1960s, China began to produce its own famous “Beijing Jeep,” a milestone in China’s national motor industry. During the Cultural Revolution, Mao, dressed in military uniform, chose to ride in the new Beijing Jeep as he saluted tens of thousands of Red Guards near Tiananmen Square, an iconic image seared into the minds of millions.111 By a strange twist of fate, the Jeep was again transformed, now into a symbol of Communist victory, pride, and superiority.