Introduction

Calls for progressive taxes are often drowned out by warnings about their detrimental effects on the economy. Taxes on the rich arguably hurt private investment, innovation, and ultimately economic growth (Okun Reference Okun1975; Steinmo Reference Steinmo2003; Fastenrath et al. Reference Fastenrath, Marx, Truger and Vitt2022). This has led governments to cut and abolish progressive taxes, even though inequality has been on the rise (Bansak et al. Reference Bansak, Bechtel and Margalit2021; Emmenegger and Lierse Reference Emmenegger and Lierse2021). However, we know surprisingly little about what the public thinks about the consequences of progressive taxation for equality and growth. This is unfortunate, as it limits our understanding of popular support for progressive taxes and their electoral appeal.

While equality-growth trade-offs are frequently debated among political (Fastenrath et al. Reference Fastenrath, Marx, Truger and Vitt2022; Hilmar and Sachweh Reference Hilmar and Sachweh2022) and academic elites (Okun Reference Okun1975), we do not know whether this represents or even resonates with concerns of the general public. As congruence between elite and public opinion is a central mechanism of democratic representation (Stimson, Mackuen, and Erikson Reference Stimson, Mackuen and Erikson1995; Broockman and Butler Reference Broockman and Butler2017; Lupu and Warner Reference Lupu and Warner2022), this is a surprising omission. Related work has shown that such opinion congruence depends on institutional contexts (Lax and Phillips Reference Lax and Phillips2012), politicians’ knowledge about constituent opinion (Broockman and Butler Reference Broockman and Butler2017) as well as motivated discounting of divergent opinions (Butler and Dynes Reference Butler and Dynes2016). We extend this line of work to policy beliefs by focusing on whether the public shares elite concerns about a trade-off between equality and growth in tax policy-making: What do citizens believe about the effects of progressive taxes? Do they believe that reducing inequality through such taxes comes at the expense of growth?

Our findings also add to a blossoming literature on taxation and redistribution, which has so far focused on explaining preferences based on material self-interest (e.g. Bechtel and Liesch Reference Bechtel and Liesch2020; Fernández-Albertos and Kuo Reference Fernández-Albertos and Kuo2018; Kenworthy and McCall Reference Kenworthy and McCall2008), beliefs about fairness and meritocracy (e.g., Ahrens Reference Ahrens2020; Boudreau and MacKenzie Reference Boudreau and MacKenzie2018; Cavaillé and Trump Reference Cavaillé and Trump2015; Mijs Reference Mijs2021), and perceptions of inequality (e.g. Becker Reference Becker2021; Engelhardt and Wagener Reference Engelhardt and Wagener2018; Gimpelson and Treisman Reference Gimpelson and Treisman2018). However, in linking these explanatory factors to policy preferences, scholars make assumptions about the beliefs individuals have about the macroeconomic effects of taxation. While it is clear that beliefs, for example about distributive effects, vary widely, they have rarely been empirically researched (for recent exceptions, see Barnes Reference Barnes2021; Stantcheva Reference Stantcheva2021). Our paper therefore fills an important knowledge gap, by shedding light on the public’s beliefs about the economic consequences of taxing the rich.

We study policy beliefs with a conjoint experiment carried out at the height of Germany’s 2021 national election campaign, during which parties clashed over the right set of economic policy, discussing issues of equality and growth. Given the timing, the main issue in the campaign was Covid-19 and the respective government actions on it. Nevertheless, surveys at the time indicated more than 90 percent of voters placed the issue of inequality as one of their main concerns, which has been pointed to as a reason for the strong showing of the Social Democratic Party (SPD, Faas and Klingelhöfer Reference Faas and Klingelhöfer2022). Taxation was a politically salient issue during the German national election of 2021, with competing proposals for tax reforms. According to an analysis of Twitter activity by parties during the campaign, the SPD focused on issues of social inequality, the liberal Free Democratic Party (FDP) on the economy and taxes, and the conservative Christian Democratic Union on domestic and economic policy—while the Greens naturally paid disproportionate attention to the environment (Wurthmann Reference Wurthmann, Campbell and Louise2023). Center-left parties advocated for tax increases on high incomes, wealthy individuals, and large multinationals to lower the burden on lower- and middle-class households and to finance the debt that had been accumulated as a result of the pandemic. Right-of-center parties, in turn, resisted any tax increases, including for top earners, and proposed balancing the budget through austerity measures (Cassell and Deutsch Reference Cassell, Deutsch, Campbell and Louise2023).

The context of the national elections provided a most-likely case for testing to what extent the elite discourse on the efficiency-equality trade-off resonates in the public. First, as we show, there were mainstream parties supporting very different positions around those topics. Second, due to the salient electoral competition, we may expect that during this period people are more aware of these arguments than at other times. Not only that, but this also makes it more likely to identify partisan effects: voters of certain parties are more likely aware of their parties’ positions on these topics during the campaigns, and therefore of taking the party cues for their own positions, as well-known from theories of partisan cues and public opinion formation (Zaller Reference Zaller1992; Slothuus and de Vreese Reference Slothuus and De Vreese2010). Therefore, fielding the experiment during electoral season increases the likelihood that voters are more aware of these topics, have more informed opinions and give more meaningful answers that align with party preferences and elite debate.

Our survey experiment uses a conjoint design with 1360 participants that are representative of the German population with regards to gender, age, and place of residence. Participants were asked to choose between five pairs of tax reform packages with randomly varying attributes (i.e. tax increases or decreases on the rich or in general) on three different tax dimensions: income, wealth, and corporate taxation. In particular, participants have to decide whether a package is more conducive to equality or to growth. This design allows us to assess how beliefs about tax changes for the rich differ from tax changes in general and thus to capture whether they align with the argument that taxes on the rich benefit equality but harm growth.

Contrary to received wisdom, we find that the average participant in our study regards equality and growth to go hand-in-hand when thinking of the effects of progressive taxation, at least when it comes to both personal income and inheritance taxation: tax increases for the rich contribute to equality and growth, while tax decreases for the rich are seen as harmful to both. This pattern is less clear for corporate taxation, where tax increases for large corporations promote equality but are not perceived to affect growth in any way. Surprisingly, we also do not find evidence of a heightened trade-off logic among conservatives or participants that stand to lose from a given policy package.

Overall, the results of this study contribute to our understanding of beliefs about tax policy on several accounts. Our experimental study shows that contrary to debates among political elites, the German public believes that higher taxes on the rich can promote both equality and economic growth. Although we studied the German context, a country belonging to the cluster of coordinated welfare regimes, the findings are more generalizable. Stantcheva (Reference Stantcheva2021), who studied the public’s views on taxation in the United States a liberal market economy—also did not find that concerns about economic efficiency affected tax attitudes. Moreover, the redistribution literature generally finds relatively small differences in the public’s beliefs between welfare regimes (Jaeger Reference Jaeger1997; Svallfors Reference Svallfjors1997). In other words, our study suggests that the public is more critical about many of the implicit assumptions underlying economic models, which elites often take for granted, even beyond the German context.

Yet, our study also highlights that these effects vary by the type of tax. It shows the importance for future research of disentangling between personal and corporate taxation when studying preferences for redistribution. Finally, learning about citizens’ beliefs on the expected outcomes of different tax packages leads to a better understanding of tax preferences: support for progressive taxes appears to rest on a strong foundation of macroeconomic beliefs. This suggests that there is a disconnect between popular and elite discourse, whereby the latter is more aligned with concerns of economically liberal interest groups. As such, our findings attest to the importance of studying policy beliefs to understand preference formation and add an additional layer to studies on democratic representation and responsiveness (Gilens Reference Gilens2012; Peters and Ensink Reference Peters and Ensink2015).

Public beliefs about the effects of taxation

Public opinion scholars highlight a variety of factors that influence preferences for taxation. While perceptions of inequality and behavioral motives receive most attention (e.g. Ballard-Rosa et al. Reference Ballard-Rosa, Martin and Scheve2017; Mijs Reference Mijs2021; Trump Reference Trump2018; Stiers et al. Reference Stiers, Hooghe, Goubin and Lewis-Beck2022), policy beliefs have not played such an important role. We use the term to refer to people’s beliefs about the effects of policies. Policies have a virtually infinite number of effects, but public debates usually highlight specific economic, ecological, and social effects.

We are particularly interested in beliefs about the macroeconomic effects of tax policies. On the most basic level, studying policy beliefs allows us to study assumptions that are often taken for granted. Unlike other studies (e.g., Bechtel and Liesch, Reference Bechtel and Liesch2020), we are interested in whether individuals actually believe that higher taxes on the rich are an effective means of redistribution or, alternatively, whether they fear that this has reverse effects on economic growth. In other words, we explore people’s policy beliefs and aim to better understand how people think about the effects of taxes. These policy beliefs rest on macroeconomic assumptions about how the world works as well as empirical observations.

Policy beliefs exist as part of macroeconomic belief systems. In the absence of studies dedicated to individual belief systems, we turn to larger policy debates and paradigms that have defined the past decades. When it comes to taxation, two policy goals in particular--equality and growth--are often seen to conflict. Such equality-efficiency trade-off concerns are especially controversial when it comes to taxing the rich. In 1975, Okun distilled this paradigm and popularized the leaky bucket metaphor in his book Equality and Efficiency: The Big Trade-off:

“With very few exceptions, … redistribution cannot be carried out costlessly: as I like to put it, we can transport money from rich to poor only in a leaky bucket. Some obvious leakages include administrative and compliance costs of implementing both tax and transfer programs, altered and misplaced work efforts resulting from them, and distortion of innovative behavior as well as saving and investment behavior” (ibid, p.119).

As such, economic resources cannot be transferred from the rich to the poor without incurring losses. These losses result from administrative costs, smaller work incentives, and reduced investments, especially in innovative activities. These arguments are still commonplace in political debates and they define ideological positions of public officials and parties (Fernández Gutiérrez and Van de Walle Reference Fernández-Gutiérrez and Van de Walle2019). However, not all tax policies are believed to have the same macroeconomic effects and thus might induce trade-offs to greater or lesser degrees. Again, Okun (Reference Okun1975) offers important guidance:

“The presence of a tradeoff between efficiency and equality does not mean that everything that is good for one is necessarily bad for the other. Measures that might soak the rich so much as to destroy investment and hence impair the quality and quantity of jobs for the poor could worsen both efficiency and equality. On the other hand, techniques that improve the productivity and earnings potential of unskilled workers might benefit society with greater efficiency and greater equality. Nonetheless, there are places where the two goals conflict, and those pose the problems” (ibid, p.4).

The propositions of the leaky bucket argument, in particular the trade-off between equality and efficiency, have been subject to considerable debate. In fact, two main competing economic paradigms exist that have influenced the discussion on tax policy-making since the post-war era (Martin Reference Martin1991). While the progressivity approach suggests that growth and revenues can follow from redistribution, the economic incentive approach does not regard progressive taxes as compatible with efficiency goals.

Until about the 1980s, the progressivity approach was dominant, according to which redistribution and economic growth are compatible goals (Martin Reference Martin1991; Lierse Reference Lierse2011). According to this paradigm, it is possible to simultaneously levy taxes on high incomes and wealth while also achieving equality and efficiency goals. However, since then economic ideas have shifted towards a more efficiency-oriented paradigm, which highlights how progressive taxes disincentivize people from saving and investing. While taxation is still considered necessary because the state needs revenue to provide public goods, redistribution from high-income classes and capital-intensive sectors are considered a deterrent to economic growth. The argument is that economic growth is welfare enhancing as such and thus, concerns about redistribution are therefore secondary. Such trickle-down arguments are nowadays popular among conservative policy-makers and parts of the public.

While the academic and policy macroeconomic debates have been going on for decades, it is not at all clear whether the general public also believes progressive taxation to have conflicting consequences for equality and efficiency. Recent scholarship has started to address public beliefs about how the economy works, and how those descriptive assessments can inform public preferences. Rubin (Reference Rubin2003) proposes that a large part of the public believes the economy to be a zero-sum game, where benefits to some mean that others have to incur losses. This, Rubin argues, is in contrast with the dominant view by contemporary economists, who regard the economy to be a positive-sum game, whereby transactions lead to overall growth that can benefit some without impoverishing others. However, the empirical analysis by Barnes (Reference Barnes2021) reveals that few individuals hold clear-cut positive-sum or zero-sum views and frequently endorse beliefs that combine elements from both perspectives.

Most relevant for our argument is the study by Stantcheva (Reference Stantcheva2021), which uses survey data from the United States to uncover how beliefs about taxation affect support for progressive taxes. She finds that only a minority of respondents (31%) believe that increasing taxes for high incomes would harm economic growth, the same proportion (32%) who believe in “trickle-down economics”, i.e. that lowering taxes on the rich would also uplift the poor by promoting growth (Stantcheva Reference Stantcheva2021, p. 2336–2339), and that such views are associated with lower support for progressive taxation. Importantly, the beliefs about tax effects do not vary depending on respondents’ own level of income, but there is a stark disparity between Democrats and Republicans, whereby Democrats regard higher taxes on the rich to improve equality to a greater degree, while Republicans tend to believe in the trickle-down effect of cutting taxes for the rich. These descriptive findings are bolstered with experimental evidence, showing that increasing knowledge about the redistributive impacts of taxation strengthens demand for progressivity but information about adverse efficiency effects induces no change. One exception is support of an estate tax for wealthy individuals, which the efficiency treatment increases among Democrats, possibly suggesting a belief in growth-promoting effects, but decreases among Republicans. No similar treatment heterogeneity is found for income taxation.

The literature shows that elite debates on the equality-efficiency trade-offs of progressive taxation do not necessarily translate seamlessly into public beliefs. To explicitly test whether the public believes that equality and growth are competing objectives of progressive taxation, we formulate our two main hypotheses, which should both be true if the trade-off logic held significant sway.

H1: Tax increases for rich individuals and large companies are more likely to be considered beneficial to economic equality than general tax increases (equality effect).

H2: Tax increases for rich individuals and large companies are more likely to be considered harmful to economic growth than general tax increases (growth effect).

The hypotheses specify our expectations regarding taxes on the rich relative to general changes in tax levels. Although a comparison to the status quo might seem more intuitive, such a comparison varies two factors, tax progressivity and tax levels, and it would not be possible to distinguish their effects. Comparisons to the status quo would thus be confounded and not allow us to draw any clear conclusions about the effects of tax progressivity. Therefore, it is theoretically and methodologically sound to compare changes in taxes on the rich to general tax changes.

Furthermore, we propose that equality-efficiency trade-offs do not apply equally to all types of taxation. Prior studies have shown that people have distinct views about different types of taxes (Barnes et al. Reference Barnes, de Romément and Lauderdale2024; Bartels Reference Bartels2005; Bremer and Bürgisser Reference Bremer and Bürgisser2024; Hammar et al. Reference Hammar, Jagers and Nordblom2008; Kneafsey and Regan Reference Kneafsey and Regan2022). In our study we focus on three main types: taxes on personal income, corporate income, and inherited wealth. While all three of them can be progressive and targeted at rich individuals or large businesses, we expect people to hold different policy beliefs about these taxes. Personal income taxes, particularly progressive ones, aim to reduce income inequality by taxing higher earners more heavily. However, critics argue that steep personal income taxes may disincentivize productivity, effort, and innovation, potentially dampening economic growth (Piketty and Saez Reference Piketty and Saez2013). In contrast, corporate income taxes directly impact businesses, potentially discouraging investment, innovation, and hiring. High corporate taxes might lead to capital flight or reduced competitiveness in global markets, which could harm overall economic efficiency more acutely than personal income taxes (Auerbach and Slemrod Reference Auerbach and Slemrod1997).

On the other hand, inheritance taxes, which target wealth transfers between generations, are often seen as less distortionary. These taxes primarily affect accumulated wealth rather than current earnings or business operations. Consequently, inheritance taxes are argued to have a relatively smaller impact on investment and productivity, while significantly promoting equality by curbing the perpetuation of wealth concentration over generations (Saez and Zucman Reference Saez and Zucman2019).

Ultimately, while the efficiency-equality trade-off arguably exists across all tax types, its magnitude and nature differ. Corporate taxes often pose the greatest efficiency challenges, whereas taxes on personal income or inherited wealth may strike a better balance, depending on their design and enforcement. Hence, we formulate the following two conditional expectations:

H1a: The equality effect (H1) is smaller for taxes on companies than on individuals.

H2a: The growth effect (H2) is larger for taxes on companies than on individuals.

We also expect that beliefs about the effect of tax reforms on equality and efficiency are conditioned by the following individual factors. First, people on the right of the political spectrum see fewer benefits for equality and more risks for efficiency (e.g., Stantcheva Reference Stantcheva2021) and thus the two objectives should therefore stand in sharper contrast. We expect that ideology conditions our main hypotheses as follows:

H1b: The equality effect (H1) is smaller among more conservative individuals.

H2b: The growth effect (H2) is larger among more conservative individuals.

Second, self-interest is not only a basis for policy preferences, it also motivates people to hold certain beliefs about the world. As such, most people nurture beliefs that align with their self-interest and contribute to securing or improving their economic situation. We therefore expect that people who are more directly affected by taxation are less enticed by its equality benefits and more concerned about its efficiency risks.

H1c: The equality effect (H1) is smaller among rich individuals/employees of large companies.

H2c: The growth effect (H2) is larger among rich individuals/employees of large companies.

Though our hypotheses here focus on tax increases, we would expect the same logic to apply to tax reductions, and thus effects in the opposite direction. Therefore, we also integrate tax reductions in our survey design.

Overall, our study makes two important contributions. First, with its focus on policy beliefs, it sheds light on an understudied aspect of individual preference formation and public opinion, and complements prominent explanations of behavioral motives and subjective perceptions. Policy beliefs are of obvious relevance beyond tax policies and studying them should be most valuable where disagreements over cause-and-effect relationships are common. As such, our second contribution is to test whether elite debates about the equality and efficiency effects of different tax policies aligns with how the public thinks about taxation. It thus probes widespread assumptions among social scientists and politicians about the public’s policy beliefs.

Research design

The study, including its hypotheses and research design, has been pre-registered.Footnote 1 We conducted a conjoint survey asking participants to compare and evaluate pairs of tax policy packages (for an example, see Table 1). Conjoint survey designs are increasingly popular in public opinion studies, as multiple treatment dimensions can be accommodated (Hainmueller et al. Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014). This design is particularly useful in our case because our intention is to estimate and compare how respondents evaluate the consequences of different tax policy characteristics, including variation across types of taxes as well as changes in tax levels and progressivity. Importantly, the estimation of causal effects is done while holding other effects equal, without having to assume that respondents hold other things equal in their heads while thinking about the policies (Hainmueller et al. Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014). It is also more efficient than measuring multidimensional beliefs with direct questions, which would require a large number of lengthy questions to allow for the same comparisons and to control for possible confounders.

Table 1. Description of conjoint attributes and levels

In our conjoint survey, reform packages vary in three policy dimensions--taxes on personal income, corporate income, and inherited wealth. On each policy dimension, the package features either tax increases, decreases, or no change, whereby the changes apply to the general population or are limited to the rich. To elicit policy beliefs, participants indicate which of the two reform packages contributes more to economic growth and which contributes more to inequality reduction. The binary responses constitute our two dependent variables. It is a forced choice, meaning that participants have to pick one of the alternatives for each question. Asking about the two outcomes separately has the advantage to reduce the cognitive load for respondents as they can think about each outcome individually and provides for a more faceted elicitation of beliefs than collapsing both outcomes into one.

Overall, each participant evaluates five pairs of policy packages. The features of each package are filled randomly, such that any differences in responses can fully be attributed to differences in the tax attributes. To make sure all three tax types receive the same attention we vary their order of presentation by participant.

With three attributes and five ordinal levels per attribute, this task is not more cognitively demanding for respondents than other conjoint experiments in the political economy literature. For example, Ballard-Rosa et al.’s (Reference Ballard-Rosa, Martin and Scheve2017) assessment of Americans’ preferences for progressive taxation uses a paired conjoint with six attributes and between four and six levels per attribute, where each respondent evaluates eight pairs of tax plans. Those are similar numbers to the experiments in Rincon (Reference Rincon2023), Bechtel and Scheve (Reference Bechtel and Frederick Scheve2013), or Gallego and Marx (Reference Gallego and Marx2017), to name a few examples. With three attributes, five levels, and having respondents evaluate five pairs of tax packages, our design is squarely within the bounds of complexity usually presented to survey respondents (see, e.g. Hainmueller et al. Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014, who find that conjoints are not too demanding even with 30 tasks per respondent). Moreover, in Online Appendix A, we show the usual assumption tests for conjoint experiments, which are met. We also removed all respondents from the analysis (146) who failed the attention check, in accordance with our pre-registration plan.

We used the power analysis tool by Stefanelli and Lukac (Reference Stefanelli and Lukac2020) for conjoint experiments to define the necessary sample size and number of tasks per participant. The expected effect sizes were based on Ballard-Rosa et al. (Reference Ballard-Rosa, Martin and Scheve2017) and Gross et al. (Reference Gross, Lorek and Richter2017), who identify an increase in support of around 5% for tax increases for higher incomes. The necessary sample size was thus identified at 875 participants, which we rounded up to 1000 anticipating missing data or attention check failures.

Study participants were recruited and surveyed online with the survey company Lucid. Sampling is non-random, but we implement quotas for age, gender, and region of residence that correspond to actual population shares. To fill the quotas, our survey partner recruited a larger participant pool than we anticipated. On top of the 1000 planned participants, another 360 completed the survey. We included the additional participants in the analysis, as we had no influence on the sampling procedure and selective stopping is thus no concern.

Descriptive statistics of the sample are as follows: the median age is 46.5, with participants ranging from 18 to 85. Regarding gender, 51.9 percent identify as female, 47.4 percent as male, and 0.01 percent as other. On the 0–10 ideological self-placement scale, the average is 4.83 (SD = 2.09). Regarding party choice, 20 percent would vote for the Union (CDU/CSU), 18 percent for the SPD, 12 percent for the Greens, 9.7 percent for the AfD, 8.5 percent for the Left, and 8.1 percent for the FDP. Taking into account that around 20 percent didn’t know, didn’t answer, or were not going to vote, these shares are proportional to the numbers actually observed in the 2021 elections soon after our data collection. The question on household income asks how many percent of households in Germany the participants believe have a lower income than theirs, the average is 47 (median 46), with a standard deviation of 22.7. A complete table with demographics is in Online Appendix C.

Part of the hypotheses involve subgroup analyses. First, we capture ideological leaning using the standard left-right self-placement question from the European Social Survey, which ranges from 0 (left) to 10 (right). Participants below the middle of the scale are classified as “progressive”, while those above the middle of the scale are labeled “conservative”. Second, income and wealth are measured using a question where participants are asked to indicate, on a 0–100 scale, how many households in Germany they believe have an income or wealth lower than theirs. We classify participants who placed themselves above 50 as having high income/wealth. Finally, participants are asked about their current or most recent employment, and the number of employees in the company. Those who report working for companies with 100 or more employees are defined as working for large companies.

We analyze the data using the cregg package for R (Leeper Reference Leeper2020) and present results using marginal means (MMs) following Leeper et al. (Reference Leeper, Hobolt and Tilley2020). In this design, with a forced choice for paired outcomes, the interpretation of marginal means is the probability that a profile will be selected given that an attribute level x is present, while marginalizing across all other attributes and levels.

Results

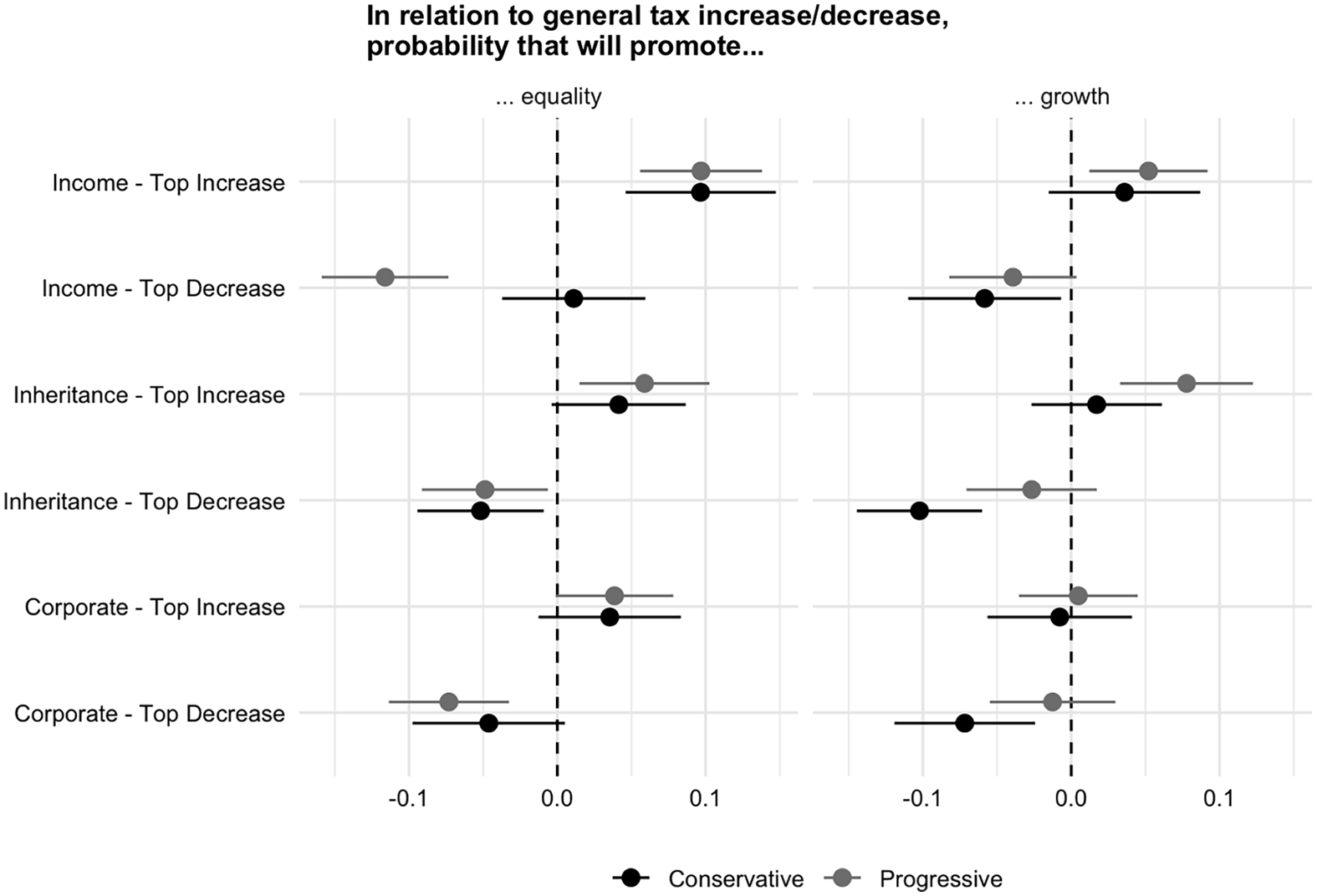

Does the public believe that equality and growth are competing objectives of progressive taxation? And what factors do these beliefs depend on? Figure 1 presents results for changes in top-bracket taxation for each tax type—both increases and decreases—in relation to general increases/decreases, including estimates and 84 percent confidence intervals.Footnote 3 The color of the dots indicates which outcome they refer to: the likelihood that the attribute level promotes growth (black) and that it promotes equality (gray). For example, the first coefficient indicates that income tax decreases for those at the top are perceived to be conducive to less equality than a general decrease of the income tax (β = −.043, SE = .017). Focusing still on income tax changes, the results indicate that German citizens do not see equality and growth as conflicting objectives: increasing taxes on the rich is perceived as a better way to promote both equality and, to a smaller but significant extent, economic growth, than general tax increases. Tax cuts for the rich, conversely, are seen as more likely to harm equality and growth than indiscriminate tax cuts.

Figure 1. Effects of tax changes for top group versus general tax changes. Notes: Average Marginal Component Effects (AMCEs). 84% confidence intervals as horizontal bars; Reference category for Top Increases (i.e., tax increases for rich individuals/large companies) are general increases for all individuals/companies; for Top Decreases (i.e., tax decreases for rich individuals/large companies) are general tax decreases for all individuals/companies.

The same pattern is observed for inheritance taxes, where the effects go in the same direction for equality and growth. The only case where we find some evidence of competing objectives is corporate taxation. Here, participants think that increases for large companies promote equality but have a negative, albeit insignificant, effect on growth. Tax cuts for large companies, however, are perceived as significantly more harmful to both equality and growth than general cuts in corporate taxes.

In terms of our stated hypotheses, the results lend support to H1, the equality effect: tax increases for high incomes, large bequests, and large corporations have a significant impact on promoting equality, and conversely tax cuts for those groups are believed to harm equality. The strongest effect, significantly larger than the other two, is for progressive income tax increases.

While our findings are supportive of H1, they are less so for H2. Increasing taxes on high income and wealthy individuals is seen as more conducive to economic growth than general tax increases, which is contrary to H2. Moreover, higher taxes on large corporations are not seen as significantly more harmful to growth than general corporate tax increases. The findings suggest that participants believe progressivity increases equality, but we do not find evidence that it is believed to harm economic growth. In sum, the results refute the idea that public beliefs about progressive taxation are characterized by trade-off thinking. In Online Appendix B, we present results using “no change” as the reference category. Estimates there also show that respondents believe higher taxes for top brackets on income and wealth have strong egalitarian effects, while the expected effects on growth are positive, albeit non-significant. Once again, only for tax hikes on large corporations does there seem to be a conflict between both objectives, where higher taxes for them are seen to promote equality but harm economic growth.

In the following section, we discuss the sub-hypothesis to gauge if this finding varies between taxes and whether it is driven by significant inter-group differences, particularly due to different ideologies or economic positions within society.

H1a and H2a propose that effects differ between the three tax types. Namely, that the effects of tax increases on equality are larger for income taxes on individuals than on corporations, while the effects of tax increases on harming growth are larger for taxes on corporations than on individuals. The results, however, only provide partial support for H1a: the effect of tax increases for high personal incomes on reducing inequality is significantly larger than for the other two, which are about the same (see Figure 1). Therefore, it is not necessarily a function of individuals versus companies, but rather income versus other forms of taxation. The same is not seen with decreases, where tax cuts for top groups in all categories have similarly sized coefficients in terms of harming equality. Turning to H2a, there is partial evidence in favor of it, namely that tax increases for rich individuals and large inheritances are believed to significantly promote growth, while tax increases for large corporations have a significantly smaller and negative effect on growth. However, this effect is not significant in itself, which is the reason why we would not consider it strong evidence for H2a.

Our findings imply that the expected trade-off between equality and growth is, for the most part, not observed among the German public. Only for corporate taxation do participants believe that an increase in tax progressivity fails to promote growth but promotes equality. For taxes on individuals, both on income and the transfer of wealth, citizens believe that higher levels of tax progressivity lead to both more equality and economic growth. For further investigation, we turn to the sub-hypotheses to assess whether these effects vary by participants’ ideology or self-interest.

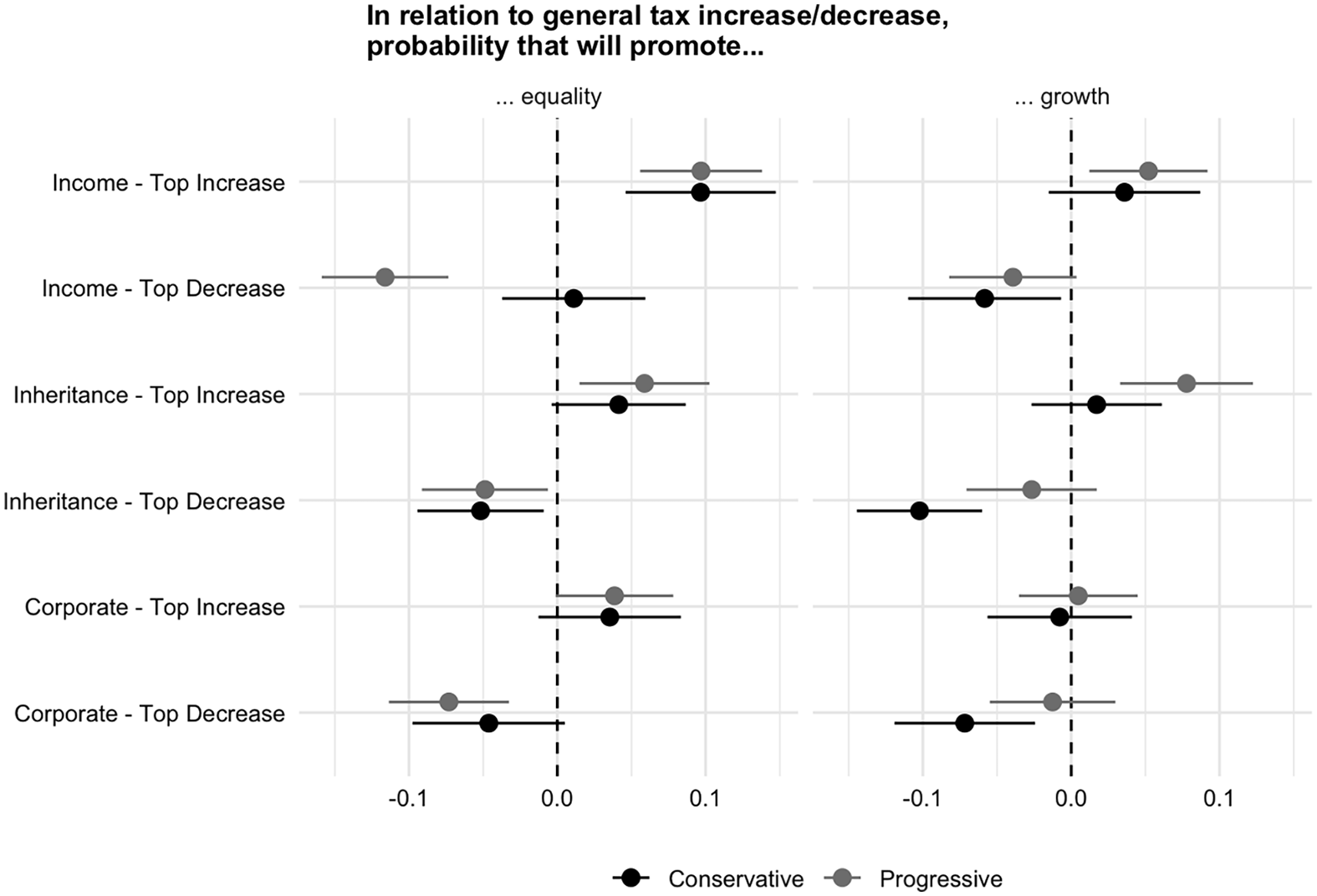

We investigate whether effects vary by participants’ ideology. H1b and H2b suggest that the equality effects are smaller for conservatives, while the growth effects are more pronounced for them. Figure 2 illustrates our results. By and large, they are not supportive of H1b and H2b, as we cannot observe different perceptions of the equality or growth effects among conservative and progressive groups. Only in the case of tax decreases for top income earners do we find a significant difference: respondents on the political left believe a regressive tax reform to have a large and significantly negative impact on equality, while those on the political right do not believe that tax cuts for high incomes are worse for equality than general income tax decreases.

Figure 2. AMCEs of top-bracket tax changes in relation to general changes—by participants’ ideology. Notes: Average Marginal Component Effects (AMCEs). 84% confidence intervals as horizontal bars; for further details, see Figure 1.

In sum, contrary to the strong partisan effects in the U.S. identified by Stantcheva (Reference Stantcheva2021), we do not find significantly different beliefs among progressive and conservative groups about the effects of progressive tax reforms in Germany. In Online Appendix B, we test these hypotheses by redefining the groups based on whether respondents voted for an economically right or left wing party, and results remain the same.

Finally, we turn to hypotheses H1c and H2c. They propose that, due to reasons of self-interest, participants with high wealth, high incomes, or working in large corporations are more likely to see the harm of tax increases for economic growth but less likely to see the potential benefits of tax increases on equality. By and large, the sub-group findings are similar to those observed for the entire sample (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. AMCEs of top-bracket tax changes in relation to general changes—by participants’ self-interest. Notes: Average Marginal Component Effects (AMCEs). 84% confidence intervals as horizontal bars; for further details, see Figure 1.

Both groups of participants believe that higher income taxes for high earners, and higher inheritance taxes for high bequests, promote equality. Both also believe that higher corporate taxes for large companies promote equality. Looking at tax cuts, the results are similar: those who would benefit from them do not perceive the cuts as having a lower impact on inequality. Turning to the growth effect, the findings are similar, as we do not observe significant differences between the two groups. In sum, we do not find evidence for H1c or H2c: self-interest does not seem to play an important role in how participants evaluate the consequences of different types of tax reforms on economic growth or inequality.

In Online Appendix B, we examine whether this self-interest argument is relevant only for a small group at the top end of the distribution. This tests whether our initial specification cast too wide a net for those who might be affected by progressive taxation by redefining self-interest as those in the top tercile of the distributions, instead of those above the mean. However, this is not the case, as the additional results corroborate the findings presented in Figure 3.

In Online Appendix A, we present the standard assumption checks for conjoint experiments: first, we find no evidence of learning effects, whereby answers to the fifth round of the experiment are systematically different from those in the first. Second, we test whether the order of packages made a difference. We do notice that participants are more likely to pick package 1 than 2 under most conditions in both outcomes. This is not entirely unexpected, as it is known from survey research that there is a bias towards picking the first option. Moreover, this indicates task difficulty, which is to be expected in this design since the question on tax policy packages expected effects is not trivial for most participants. Since all attributes, levels, and packages are randomized, estimates should not be biased, but this violation does increase the chances of type II errors, in particular for the subgroup analyses. Therefore, the results for subgroups (i.e., ideological orientation and self-interest) should be taken with that caveat in mind.

Our methodological approach assumes that respondents truthfully indicate their actual beliefs. This might not be the case when respondents engage in post-rationalization and indicate beliefs that simply justify their preferences (Blumenau Reference Blumenau2025). In this case, respondents might express beliefs about positive effects of a tax without actually holding such beliefs. While this is a valid concern, two pieces of evidence suggest that post-rationalization is limited. First, in a majority of the pairwise comparisons (51.8%) respondents state that the effects go in opposite directions, and only 17% of respondents indicate in each of their five comparisons that effects always go in the same direction. Together, this suggests that respondents carefully weigh their answers rather than simply claim beneficial effects of preferred policies. Second, we do not find more pronounced beliefs among groups whom we know to hold strong tax preferences. Earlier studies show that left-leaning individuals as well as those who would gain from redistribution are more supportive of taxes on the rich (Ballard-Rosa et al. Reference Ballard-Rosa, Martin and Scheve2017; Stiers et al. Reference Stiers, Hooghe, Goubin and Lewis-Beck2022). However, we do not find that these groups express more positive beliefs about progressive taxes.

Conclusion

Policy beliefs are a surprisingly understudied determinant of individual preference formation. Policies are instruments to achieve societal goals that individuals might find desirable for a variety of egoistic and altruistic reasons. However, even if people share goals, they can disagree about the right policies to reach these goals if they hold different beliefs about their effects. It is thus no surprise that politicians and parties often spar over the right set of policies by promoting different belief systems, often in ideological packages.

Using a conjoint experiment, we have explored what beliefs individuals hold about the effects of progressive tax policies. Contrary to what is often discussed among political and academic elites, we find no evidence that the public, or even parts of it, believes that growth and equality are competing outcomes. While we do find support for the hypothesis that people believe that taxing the rich increases equality, they do not believe that it hampers economic growth. Instead, people largely believe that taxes on the rich promote both equality and growth, especially when it comes to personal income and inheritance taxation.

The findings echo work by Leiser and Aroch (Reference Leiser and Aroch2009), who suggest a “good-begets-good” heuristic to explain public beliefs about complex economic phenomena. According to this heuristic, individuals assume desirable outcomes—in our case equality, growth, and progressive taxes—to be causally related in order to reduce economic complexity. Our findings also relate to a recent behavioral experiment on the effect of redistribution on investment behavior (DeScioli, Shaw, and Delton Reference DeScioli, Shaw and Delton2018). The authors find that experimental subjects are more likely to take risks and invest when subsequent gains and losses are equally distributed. This suggests that one’s own willingness to invest, or observing that of others, might be the basis for beliefs in the growth-inducing effects of progressive taxation.

In line with Stantcheva (Reference Stantcheva2021), we find that self-interest motives do not change people’s beliefs about taxes. That is, even those who might be more affected by higher taxes in a progressive taxation system still see its benefits for equality, while not believing in harmful effects on economic growth. This may be due to misperceptions of one’s position on the income/wealth scale, whereby higher income individuals do not consider themselves as such (Cansunar Reference Cansunar2021). The lack of ideological heterogeneity in our study also aligns with Neuner and Wratil (Reference Neuner and Wratil2020), who, in another conjoint experiment on voting behavior in Germany, find a cross-partisan majority to be consistently in favor of higher taxes for the rich.

Substantively, our findings therefore suggest that conservative politicians and pundits peddle a trade-off that has little support even among their adherents, whereas progressives might be unnecessarily wary about a backlash that progressive taxation might induce due to wrongly assumed wide-spread beliefs about detrimental growth effects. While it may be true that among conservative elites there is fear of the harm of increasing taxes on the rich in Germany (Fastenrath et al. Reference Fastenrath, Marx, Truger and Vitt2022), it is not at all the case that the German public also sees tax policy through the same lens. As such, German political elites do not represent the concerns of the public, and this might explain low levels of responsiveness that other studies have attested to (Gilens Reference Gilens2012; Peters and Ensink Reference Peters and Ensink2015). Notably, this aligns with growing research on how politicians, including in Germany, think voters are more conservative than they really are (Pilet et al. Reference Pilet2024). Moreover, empirical studies on the relationship between equality and efficiency have not found an adverse impact of greater equality on investment or on growth, but on the contrary the results showed a positive effect (Kenworthy Reference Kenworthy1995).

It needs to be noted that our findings only provide a snapshot of German public opinion. Earlier studies have shown that perceptions of inequality, attitudes towards it, and their relationship can vary considerably over time (Becker Reference Becker2021). While we intentionally field our survey close to a national election when tax issues tend to be more salient and controversially discussed, it is possible that there are other situations, in which the congruence between public and elite opinion increases. For example, Emmenegger and Marx Reference Emmenegger and Marx(2019) provide such evidence for a national referendum of a highly progressive inheritance tax in Switzerland. The evidence suggests that it is in principle possible for elites to shape beliefs about taxation when the stakes are sufficiently high. Yet, our finding is in line with other studies that have shown that economists’ opinions differ from that of ordinary Americans (Sapienza and Zingales Reference Sapienza and Zingales2013). The explanation most consistent with their evidence is that people do not trust many of the implicit assumptions underlying the opinion of economists.

In the next step, it will be important to study how policy beliefs impact policy preferences. In our study, nothing was at stake for our participants. While prior studies have shown that progressive taxes enjoy high public support (Barnes et al. Reference Barnes, de Romément and Lauderdale2024), individuals can also hold and vote according to preferences that go against their self-interest (Bartels Reference Bartels2005). It remains an open question to what extent policy beliefs underpin these patterns. As such, it is worth asking whether earlier studies mistook selfishness, in-group favoritism, or conservatism for pessimistic beliefs about the effectiveness of policies. It would also be important to revisit Barnes’ (Reference Barnes2021) arguments about the relationship between descriptive views of the economy and redistribution preferences: for instance, is it the case that holding a view of the economy as zero-sum or positive-sum is also connected to beliefs about what the macroeconomic effects of progressive taxes are? Last but not least, it also remains an open question to what degree beliefs affect attitudes causally, or whether causality might run in the opposite direction (Blumenau Reference Blumenau2025).

Our findings are subject to a number of caveats. First and foremost, we worked with a broad quota sample of the German population, which does not constitute a fully representative sample. While our fndings are likely to apply to large parts of the German population, further studies need to explore how common the beliefs that taxes promote equality and growth are. It is possible that underrepresented groups (e.g. non-internet users) hold systematically different beliefs. Second, our coding of ideology forces us to ignore large parts of the sample in the corresponding analyses. This decreases statistical power and the results are less reliable than our other analyses. They should therefore be regarded as preliminary and carefully scrutinized by future studies.

Looking forward, we need to better understand the origins and internal consistency of policy beliefs. What is the role of political actors, schools, the media, family, and friends? Answers to these questions will improve our ability to strengthen public knowledge about policies and enable voters to make more informed choices.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X25100858

Data availability statement

Replication materials are available in the Journal of Public Policy Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/R5SDWN.

Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of this paper have been presented at the Annual Meeting of the European Political Science Association (Prague, 2022), the ECONtribute Excellence Cluster RA Political Economy Workshop (University of Cologne, 2022) and the Political Economy Workshop (University of Bremen, 2021). We thank all participants and in particular Leo Ahrens, Michael M. Bechtel, Kris-Stella Trump, David Weisstanner, and Alon Yakter for helpful comments and suggestions. All remaining errors are our own; no conflicts of interest declared.