Introduction

Since the Industrial Revolution, when modern cities emerged as a result of centralized production and the necessary influx of workers, land use, housing, and the political economy thereof became a central issue in urban (Ricardo Reference Ricardo1821; Ryan-Collins, Lloyd, and Macfarlane Reference Ryan-Collins, Lloyd and Macfarlane.2017). This issue is again becoming increasingly visible today. Current inflation levels in the Global North, ongoing capital investment in housing since the 2008 financial crisis (Aalbers Reference Aalbers2016; Rolnik Reference Rolnik2019), and a persistent reliance on market-oriented measures to produce housing are driving the conflict at the macroeconomic level. Simultaneously, the need for climate adaptation and environmental protection makes housing development within ecological limits an increasingly urgent issue (Angelo and Wachsmuth Reference Angelo and Wachsmuth.2020).

Scholarly attention to housing politics has steadily increased in recent years (Ansell et al. Reference Ansell2022; Cansunar and Ansell Reference Cansunar and Ansell.2021; Hankinson Reference Hankinson2024). While there is a rich body of literature explaining preferences for (re)distributive policies based on individuals’ positions in the labor market and related income streams, we lack a coherent explanation for how preferences regarding housing development can be understood (Ansell Reference Ansell2014; Ansell Reference Ansell2019). For instance, cross-country evidence shows that homeowners become less supportive of redistributive spending during periods of rising house prices (Ansell Reference Ansell2014). Here, the duality of housing as both a basic human need and a commodity (Marcuse and Madden Reference Marcuse and Madden.2016) further complicates housing preferences. Thus, understanding how individuals perceive housing production in relation to social welfare, state regulation, and globalized financial markets becomes crucial for those interested in public opinion and policy preferences aimed at overcoming housing affordability challenges.

Although there is broad public and scholarly consensus that densification – defined as higher population or use densities in already densely populated areas – is desirable and urgently needed for both social and ecological reasons (Boyko and Cooper Reference Boyko and Cooper.2011; Einstein, Glick, and Palmer Reference Einstein, Glick and Palmer.2019; Manville, Monkkonen, and Lens Reference Manville, Monkkonen and Lens.2020), densification projects in urban and suburban areas often face opposition from existing residents (Dunham-Jones Reference Dunham-Jones2005; Einstein, Glick, and Palmer Reference Einstein, Glick and Palmer.2019; Lewis and Baldassare Reference Lewis and Baldassare.2010; Monkkonen and Manville Reference Monkkonen and Manville.2019; Wicki and Kaufmann Reference Wicki and Kaufmann2022; Wicki, Hofer, and Kaufmann Reference Wicki, Hofer and Kaufmann2022). To date, political science research has primarily focused on owner-occupied housing and the behaviors and negative externalities associated with this group of residents.

Leveraging the Swiss case – a high-income housing market with the highest percentage of renters in Europe and direct democratic means to influence housing policy – this article contributes to the debate surrounding urban housing development. In multiple and interacting ways, the Swiss case stands out as a clear outlier among European and OECD housing markets. In 2021, 57.8% of households rented their homes, making Switzerland the highest-ranked country in Europe (Eurostat 2022). In the two largest Swiss cities, Zürich and Geneva, over 90% of households are renters (Federal Statistical Office 2023). Financial and monetary stability – which reduces the need to protect against inflation – along with a high-quality rental stock, explain why renting is often the more rational choice. High land and real estate prices, combined with stringent requirements for owners’ equity, create mechanisms that exclude many individuals from homeownership (Theurillat, Rérat, and Crevoisier Reference Theurillat, Rérat and Crevoisier.2015; Ansell Reference Ansell2019).

In recent years, housing has become a more salient issue due to economic and demographic growth. In 2013, the Swiss voting population decided in a national referendum to reduce urban sprawl, with densification as the guiding principle in the revision of the National Spatial Planning Act. Since federal adaptation in 2014, cantons have revised their cantonal structure plans, and municipalities are still in the process of aligning with the new cantonal regulations. The implementation of measures promoting densification has varied, with a lack of progress often attributed to public opinion and low support for housing densification (Debrunner, Hengstermann, and Gerber Reference Debrunner, Hengstermann and Gerber.2020; Pleger, Lutz, and Sager Reference Pleger, Lutz and Sager.2018; Pleger Reference Pleger2019; Wicki and Kaufmann Reference Wicki and Kaufmann2022). The consequences include a slow uptake of urban densification and a sluggish pace of urban housing production. In addition, the profit-oriented implementation of densification (Debrunner Reference Debrunner2024; Debrunner and Kaufmann Reference Debrunner and Kaufmann.2023) has increasingly led to spatial injustices such as unaffordability, displacement, and gentrification (Kaufmann et al. Reference Kaufmann2023; E. Lutz, Wicki, and Kaufmann Reference Lutz, Wicki and Kaufmann.2024). Additionally, housing affordability challenges have intensified in the Swiss housing market, which is linked to a benchmark interest rate. In June 2023, the benchmark rose for the first time since 2008, permitting landlords to increase all rents, including those of existing tenants.

Given the relevance of the housing issue and its direct democratic context, we argue that the Swiss setting presents a unique opportunity to assess attitudes towards urban housing development and to explore the politicization of the housing question (Ross Reference Ross2011; Morley and Pafka Reference Morley and Pafka.2023). Based on original survey data (N = 3497) from the adult resident population of all Swiss cities and small and medium-sized towns (SMSTs), this article employs a three-step research design. First, we examine who accepts housing densification by testing arguments from the political science and planning literature regarding opposition to urban development. Second, we utilize experimental conjoint data from the same survey population to investigate whether policy design influences the acceptance of housing densification. Third, we integrate the results from the first into the second step and examine preferences within subgroups of respondents for each housing attribute individually.

In the first analysis, we find lower acceptance of housing densification among individuals facing higher housing costs relative to household income and those who self-identify as politically right-leaning. Furthermore, residents’ self-perception of their settlement type appears to influence their views on housing densification, with residents in high-density areas showing higher acceptance than those in low-density areas. In the second analysis, empirical evidence from the conjoint experiment reveals clear preferences for cost-rent models, public or non-profit developers, moderate increases in population density, mixed-use developments, democratic decision-making, climate measures, and the provision of green space. However, when exploring subgroup heterogeneity, we observe that group differences based on political ideology influence preferences regarding socio-economic and ecological measures. In summary, our study illustrates the multifaceted dynamics shaping public opinion and behavior regarding housing densification in Swiss cities and towns, demonstrating that such development is widely accepted. Importantly, our findings reveal a broad coalition of support for affordable housing across various social and ideological groups. This coalition highlights a clear preference for affordable, non-profit-oriented solutions over profit-driven developers.

The article is structured as follows: To derive theoretical expectations, we review the literature by differentiating between two levels: the individual level, where we explore attitudes towards densification from a political science perspective, and the policy level, which examines policy-driven influences on densification in relation to spatial planning literature. Here, we also outline our theoretical expectations. Subsequently, the data and method section highlights the survey data collection. Our analysis features a three-tiered methodological design. First, we model the associations of housing costs, settlement type, and political ideology on the acceptance of housing densification at the individual level. Next, we present general results from the conjoint experiment. The final step leverages individual-level attitudes against the conjoint data to differentiate subgroup heterogeneity. Following a discussion of the findings, we link the article’s contributions to the existing literature, highlighting potential implications for policymakers and future research. While our empirical focus is on Switzerland, we examine behavioral mechanisms such as relative housing cost burdens, neighborhood context, and political ideology that are relevant for urban housing debates in other democratic settings facing affordability pressures and contested densification.

Theoretical expectations

Urban and housing densification are contested issues in cities worldwide. In this article, we view the contestation and opposition to urban development as broader behavioral components of urban life and politics. In relation to growth machines (Molotch Reference Molotch1993) and housing capitalism (Campbell, Tait, and Watkins Reference Campbell, Tait and Watkins.2014), we consider housing development a political activity in which various groups compete for access to urban land, shelter, and other resources. This group conflict ultimately manifests through policy-making and planning. Following Pendall (Reference Pendall1999), we acknowledge that housing opposition is multifaceted and often has merit on multiple dimensions; it can also represent a democratic practice of participation and community building. To contribute to the debate on who accepts or opposes housing densification and the extent to which policy design influences acceptance, the following sections will categorize and discuss the current literature across individual and aggregate-level dimensions.

Individual level

In explaining the acceptance of urban development, particularly densification, at the individual level, the existing literature can be categorized into three strands. The first strand is economically driven, focusing on self-interest, while the second emphasizes a socialization logic, where societal factors shape individual beliefs and attitudes. The third strand emerges from a critique of the previous explanations, highlighting the politicized nature of housing production. By reviewing and discussing each of these strands, this section formulates contrasting hypotheses for the empirical analysis.

Firstly, NIMBYism (Not-in-my-backyard) is widely recognized as the dominant theory explaining opposition to housing development. This theory views the market behavior of residents from a local-politics perspective, suggesting that homeowners leverage institutional mechanisms to maintain or enhance their property values by restricting the supply of housing. This behavior often contributes to rising prices (Pendall Reference Pendall1999; Charmes, Rousseau, and Amarouche Reference Charmes, Rousseau and Amarouche2021; Einstein, Glick, and Palmer Reference Einstein, Glick and Palmer.2019; Marble and Nall Reference Marble and Nall.2021; Schaffner, Rhodes, and La Raja Reference Schaffner, Rhodes and La Raja.2020; Trounstine Reference Trounstine2016; Trounstine Reference Trounstine2018; Whittemore and BenDor Reference Whittemore and BenDor.2019). Building on this foundation, more nuanced explanations emerge, focusing on interactions such as the relationship between individual political beliefs and home renting or ownership (Michael Hankinson Reference Hankinson2018; Marble and Nall Reference Marble and Nall.2021). Additionally, proximity-based utility-seeking suggests that residents in high-demand neighborhoods may express reservations about densification due to concerns about effects like displacement or escalating living costs (Hankinson Reference Hankinson2018; Rérat Reference Rérat2019; Michael Hankinson and Benedictis-Kessner Reference Hankinson2024). Other factors include ideological grounds for opposing redevelopment (Wicki, Kauer, et al. Reference Wicki and Kauer2023), and the relationship between proximity to housing densification and racist or classist resentments directed at groups associated with such developments (Trounstine Reference Trounstine2021; Charmes, Rousseau, and Amarouche Reference Charmes, Rousseau and Amarouche2021). Furthermore, structural and regulatory differences in housing markets and ownership models warrant consideration. From a comparative perspective, Ansell (Reference Ansell2019) highlights the heterogeneity between Anglo-American “ownership societies” and Western European “welfare state” systems, attributing this to credit market regulation and property taxation as governmental intervention mechanisms in housing markets. In this context, opposition to housing development is once again explained through self-interest, where the “growing value of housing has increased the wealth of homeowners and lowered their demand for government spending and redistribution.” (Ansell Reference Ansell2019, p. 182). Examining these redistributive preferences during periods of rising housing unaffordability, Cansunar and Ansell (Reference Cansunar and Ansell.2021, p. 597) find that European individuals, on average, become “less supportive of redistribution, interventionist housing policy and left-wing parties.”

Thus, we anticipate that acceptance of housing densification is less likely among individuals facing higher relative housing costs in a renters’ society. This is particularly relevant in the Swiss context, where evidence shows that interventions like (market-based) densification rather lead to price increases and affordability issues for local residents, with involuntary relocation a likely outcome (E. Lutz, Wicki, and Kaufmann Reference Lutz, Wicki and Kaufmann.2024; Kaufmann et al. Reference Kaufmann2023), while densification being predominantly implemented through the demolition of old, yet affordable housing (Debrunner Reference Debrunner2024).

Exp. 1: The acceptance of housing densification is less likely in individuals facing higher relative housing costs.

Secondly, socialization-oriented explanations expand on economic motives by emphasizing how the living environment influences individuals’ behaviors. Larsen and Nyrup (Reference Larsen and Nyrup.2022) offer an explanation that is less driven by economic determinants, finding that citizens’ opposition to new housing development is more pronounced in expensive housing markets. Using geocoded survey data from the U.S. population, the authors identify an effect of housing prices on public opinion and propose a “localist” model of urban development opposition. This model explains how rising housing costs attract citizens with preferences for local preservation in a given area, thereby limiting city governments’ capacity to (re)develop and address urban sprawl, climate adaptation, and affordable housing. This finding aligns with the observation that the acceptance of urban development can differ within cities or neighborhoods based on the built density of an area (Wicki and Kaufmann Reference Wicki and Kaufmann2022). Consequently, we posit that the acceptance of housing densification corresponds to the geo-spatial distribution of individuals across various settlement types, with individuals tending to choose settlement types as close to their ideal preferences as markets allow. Hence, the article posits that individuals’ attitudes and preferences towards housing densification will reflect the density of their current residential choices, with residents of low-density areas being less likely to accept housing densification.

Exp. 2: The acceptance of housing densification is less likely among residents of low-density settlements.

Finally, while both strands of literature discussed above highlight individual behavior to explain opposition to housing development, they implicitly address issues of redistribution without fully considering the inherent group conflicts that arise from distributional decisions. This analysis relies heavily on data from the North American context. While this focus has contributed to productive discourse, it has also resulted in a critical lack of consideration for cross-country heterogeneity in housing markets and institutional designs that influence individual and collective behaviors (Kholodilin et al. Reference Kholodilin2023). Evidence frequently reveals ideological dissonance, with liberal-oriented individuals opposing the development of new housing aimed at affordability (Hankinson Reference Hankinson2018; Hankinson, Magazinnik, and Sands Reference Hankinson, Magazinnik and Sands.2022; Marble and Nall Reference Marble and Nall.2021). Other studies indicate that liberal-oriented individuals are more likely to support regulated densification, which contrasts significantly with the views of their conservative counterparts (Wicki, Kauer, et al. Reference Wicki and Kauer2025).While evidence from the U.S. suggests a strong division along the homeowner–renter line, findings from the German housing market indicate that opposition to housing development often serves as a proxy for socio-economic or redistribution issues, delineating along a left–right dimension and generally garnering support among left-leaning electorates (Beckmann, Fulda, and Kohl Reference Beckmann, Fulda and Kohl.2020). Following this debate on political alignment regarding housing densification and the argument that housing serves as a proxy for socio-economic or redistributive political conflict (Beckmann, Fulda, and Kohl Reference Beckmann, Fulda and Kohl.2020),we anticipate that the acceptance of housing densification will be less likely among right-leaning individuals.

Exp. 3: The acceptance of housing densification is less likely among right-leaning individuals.

Across these strands, we aim to move beyond binary interpretations of residents being either in favor or against densification, by examining how attitudes vary depending on how densification is designed and justified. The theoretic expectations aim to cover a broad range of explanations for opposition to urban development and densification at the individual level. This approach not only facilitates the testing of each strand’s explanatory power but also provides an opportunity to assess the Swiss case in close comparison to other well-studied instances.

Policy level

While the literature strands discussed above adopt a demand-side perspective, the following section shifts to a supply-side view of urban development, enabling us to connect housing policy with urban and spatial planning perspectives.

Often portrayed as technical decisions regarding what is developed and where, spatial planning includes an inherently political dimension. From a technicist perspective, the objective of spatial planning “is to serve an economic, social and political order in which its role is to make that order function smoothly.” (Marcuse Reference Marcuse2016, p. 119). In this context, democratic opposition and a lack of acceptance – often attributed to prolonged planning processes and approvals – stand in contrast to the goal of “efficient functioning.” (Marcuse Reference Marcuse2016, p. 119). Some explanations for opposition to urban development arise from the elitist and exclusionary nature of planning (Pendall Reference Pendall1999; Angelo and Wachsmuth Reference Angelo and Wachsmuth.2020; Campbell, Tait, and Watkins Reference Campbell, Tait and Watkins.2014), angelo 2020, campbell 2014, while other explanations focus more broadly on preferences for governmental regulation, such as the extent of government intervention in housing development and real estate markets (Manville Reference Manville2021; Manville, Lens, and Monkkonen Reference Manville, Lens and Monkkonen.2022; Rodríguez-Pose and Storper Reference Rodríguez-Pose and Storper.2020). Consequently, the opportunities for political conflict stemming from planning activities as a form of government intervention are multidimensional and complex, both in real-world contexts and within scholarly debate (Whittemore and BenDor Reference Whittemore and BenDor.2019; Wicki, Hofer, and Kaufmann Reference Wicki, Hofer and Kaufmann2022; Ruming et al. Reference Ruming2024).

To understand the dynamic conflict dimensions of planning policies, such as housing development, the literature suggests that various characteristics within the spectrum of housing policy may influence how individuals perceive and evaluate housing densification projects. At this aggregate level, we aim to explain whether policy design and spatial planning instruments influence the acceptance of housing densification. Below, we identify and discuss seven policy and planning instruments, as well as housing project characteristics, that are associated with individual-level policy acceptance.

Firstly, as previously discussed regarding the individual level, housing costs are significant at the project level. Housing densification is often driven by their potential to alleviate housing unaffordability (Angelo and Wachsmuth Reference Angelo and Wachsmuth.2020). Inclusionary zoning has emerged as a practical policy instrument aimed at providing affordable housing. Advocated on the grounds of preventing homogeneous neighborhoods and promoting social mixing, the fundamental premise is that governments negotiate an increase in a plot’s density – allowing for the construction of more units on a single plot, thereby generating higher revenue – in exchange for a percentage of “affordable” units from developers. However, critical perspectives raise concerns about the effectiveness of this measure (Marcuse and Madden Reference Marcuse and Madden.2016), particularly regarding the reliance on market mechanisms to provide affordable housing.

Related to the market-based provision of housing, another important decision in planning revolves around who develops a plot. Non-profit housing, such as public or cooperative housing, is often viewed favorably among residents (Wicki, Hofer, and Kaufmann Reference Wicki, Hofer and Kaufmann2022). Conversely, at the other end of the public–private spectrum, Monkkonen and Manville (Reference Monkkonen and Manville.2019, p. 1123) note that “residents might dislike development because they dislike developers,” which can be partly explained by residents’ ideological position on market regulation and government intervention in relation to housing capitalism (Pasotti Reference Pasotti2020). Others suggest that some residents might “sabotage the free market as an alleged self-defence mechanism” (Klement et al. Reference Klement2022, p. 6), linked to general opposition to growth or due to individuals’ vulnerability in housing markets and fear of involuntary relocation resulting from price increases.

The displacement of residents and other negative externalities often call into question the legitimacy of housing densification. Most planning decisions are made by an elected or appointed body, while opportunities for public participation are provided through various forms of engagement. However, the preferences of residents regarding who should ultimately make the final decision are frequently overlooked. Pendall (Reference Pendall1999) found that planning commissions typically faced less controversy than city councils in the San Francisco Bay Area during the 1980s. Yet, in the U.S., any level of government intervention is typically met with stark skepticism. Planning frequently seeks to circumvent political tensions by incorporating some form of public participation. In connection with electoral responsiveness (Pasotti Reference Pasotti2020) and the delegation of political authority (Deslatte Reference Deslatte2023), we are interested in whom residents prefer to delegate authority to, particularly in light of legitimacy concerns surrounding housing development.

Overall, in the socio-economic dimension, we anticipate that the acceptance of housing densification will be associated with residents’ perceptions of housing prices and affordability. Specifically, cost-rent measures are expected to have a more direct impact on acceptance, while the type of developer may influence project acceptance through cognitive heuristics. This is particularly relevant for individuals facing high costs and experiencing housing unaffordability, which may lead them to reject housing densification. Conversely, policies that effectively reduce housing costs could enhance acceptance among cost-pressured individuals. When considering residents’ inclusion in planning from a delegation perspective, vulnerable residents are likely to prefer greater control over the planning process, favoring projects that offer inclusive decision-making or responsive decision-makers.

Exp. 4: Individuals facing higher relative housing costs prefer the provision of cost–rent units.

Exp. 5: Individuals facing higher relative housing costs favor non-profit investors.

Exp. 6: Individuals facing higher relative housing costs prefer inclusive decision-making processes.

Secondly, socialization-oriented explanations suggest that individuals may develop a sense of place attachment to their neighborhoods, resulting in status quo preferences that resist changes perceived to alter the neighborhood. This tendency may be especially pronounced among residents who have chosen their homes based on the neighborhood’s low-density character.

To modify the density and land use of a designated area, zoning functions as the primary policy instrument. While it is frequently regarded as a technical tool, zoning has consistently demonstrated a lack of egalitarian principles. In the greater Lyon metropolitan area, efforts to mitigate urban sprawl and increase density through zoning decisions have led to “exclusionary zoning” (Charmes, Rousseau, and Amarouche Reference Charmes, Rousseau and Amarouche2021, p. 2436), exacerbating housing pressures and contributing to spatial injustices based on the resentment of privileged and vocal low-density residents against residents associated with housing densification, leading to the rejection of densification and highlighting the complexities of government interventions aimed at increasing density.

In addition to density, zoning decisions delineate settlement areas into various usages. For urban spaces, the separation has historically been most pronounced between residential and industrial/commercial uses. However, this division has recently begun to erode as mixed-use developments have gained acceptance for their integration of residential spaces with commercial and recreational amenities (Esaiasson Reference Esaiasson2014; O’Grady Reference O’Grady2020; Wicki and Kaufmann Reference Wicki and Kaufmann2022). Nevertheless, because mixed-use developments often result in denser urban environments, residents may contest these projects based on their preferences for the status quo and concerns about perceived negative effects of densification, such as the loss of green spaces, increased traffic volume, or changes in the demographics of new arrivals (Wicki, Hofer, and Kaufmann Reference Wicki, Hofer and Kaufmann2022, p. 3). Therefore, it remains to be determined what type of development residents prefer and whether strict separation or mixed usage enhances the acceptance of housing densification, as some literature suggests.

Consequently, policies that increase density or promote mixed-use development in low-density areas may conflict with residents’ preferences. Conversely, policies that preserve the existing character of neighborhoods or provide compensatory benefits could mitigate opposition and enhance acceptance.

Exp. 7: Residents in low-density settlements oppose higher densities.

Exp. 8: Residents in low-density settlements oppose mixed-usage developments.

In addition to socio-economic motivations, housing densification is often justified by environmental concerns. Bridging what we know from environmental politics, this might make the policy-design and implementation of densification even more complex, dynamic, or contested and polarizing. The motivated-reasoning account (Kunda Reference Kunda1999; Taber and Lodge Reference Taber and Lodge.2006) consistently shows that when confronted with environmental policy problems, individuals pursue various cognitive goals. This often results in increased (affective) polarization between groups, particularly in relation to anthropogenic climate change (Bolsen and Druckman Reference Bolsen and Druckman.2018; McGrath Reference McGrath, Druckman and Green2021). To mitigate potential backlashes, motivated reasoning suggests that progressively oriented individuals tend to be environmentally conscious and supportive of environmental protection efforts at both global and local levels. In contrast, environmental concerns among conservatives are predicted to increase when impacts are perceived as local, such as at the neighborhood level (Druckman and McGrath Reference Druckman and McGrath.2019; Bayes, Druckman, et al. Reference Bayes and Druckman2020; Deslatte Reference Deslatte2023). Climate communication research suggests that measures emphasizing the “efficacy of actions taken to address climate change, along with the risk of local impacts” (Deslatte Reference Deslatte2023, p. 1669) are more likely to persuade than general calls for climate mitigation. Thus, we expect that more direct, localized measures of climate change mitigation and adaptation will be associated with higher acceptance of densification overall, though significant variance is anticipated between ideological groups.

Another publicly contested issue within the ecological dimension of urban development is the provision of sufficient urban green infrastructure, recognized for offering a range of benefits, including improved air quality, pollution offset, noise reduction, and heat regulation, as well as contributing positively to urban life by enhancing residents’ psychological well-being (Grêt-Regamey et al. Reference Grêt-Regamey2020; Balikçi, Giezen, and Arundel Reference Balikçi, Giezen and Arundel.2021; Edwards Reference Edwards2019; Lin, Meyers, and Barnett Reference Lin, Meyers and Barnett2015). Thus, green spaces are essential to urban life and planning, particularly in the context of adapting to anthropogenic climate change. This raises the question of how to effectively integrate ecosystem services and nature’s contributions to people into housing densification projects. While the reliance on access to private or public green space varies among residents (Lin, Meyers, and Barnett Reference Lin, Meyers and Barnett2015), we anticipate that the provision of additional green spaces will generally enhance the acceptance of housing densification, although this acceptance may differ across various ideological groups.

Exp. 9: Right-leaning individuals prefer climate protection and adaptation measures less than their left-leaning counterparts.

Exp. 10: Right-leaning individuals prefer additional green space less than their left-leaning counterparts.

Data and method

To better understand how individual-level factors and housing policy measures influence and interact with the acceptance of housing densification, we fielded an online survey targeting the adult resident population of Swiss cities and SMSTs from January to March 2023. The survey included a conjoint experiment examining seven housing project attributes, along with questions regarding respondents’ sociodemographic information, political attitudes, and living environments. This section provides an overview of the survey procedure and the data collected (Wehr et al. Reference Wehr2025), followed by subsections detailing our three-step analytical approach.

Survey data

To define urban spaces, we adopt the definitions provided by Dijkstra and Poelman (Reference Dijkstra and Poelman.2012) and Goebel and Kohler (Reference Goebel and Kohler.2014). Accordingly, we selected municipalities with a minimum of 14,000 inhabitants, workers, or overnight stays and consisting of a dense core with at least 2500 inhabitants, workers, or overnight stays per square kilometer. In Switzerland, 162 municipalities met these criteria in 2023, representing 4.12 million residents and 47.1% of the total population.Footnote 1 We ordered the municipalities into three linguistic regions (Italian, French, and German-speaking, while omitting the Rhaeto-Romanic linguistic region) and minimally oversampled the Italian-speaking region to account for varying population sizes and ensure statistical power. We obtained an original, stratified sample of 17,542 individuals from the Swiss residents registry maintained by the Federal Statistical Office (FSO). Individuals in the sample received written invitations via mail in the primary language of their municipality, along with a personalized token to access the online survey. Due to the methodology, age was an additional selection criterion, with the included range set from 18 to 75. In total, 3,497 individuals completed the survey.

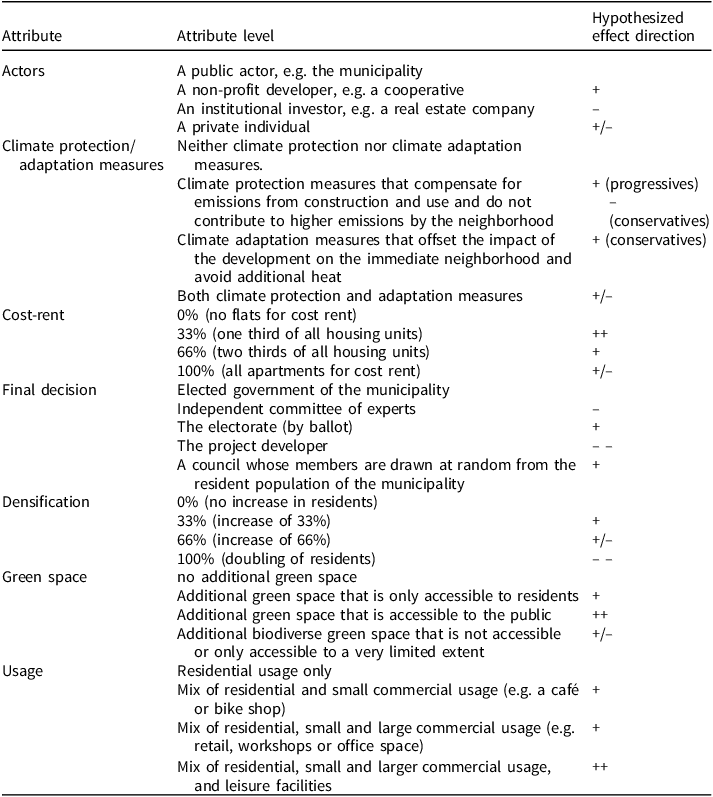

The online survey consisted of two parts. Following a brief introduction to the topic designed to minimize cognitive load and ease participants into answering questions, respondents engaged in a conjoint experiment focused on a hypothetical housing densification project. The experiment included seven housing policies and project characteristics as attributes, each with between four and five attribute levels, summarized in Table 1. Respondents were asked to indicate whether they accepted or rejected the project based on a randomization of attribute levels and whether they would accept each proposal individually, following the methodology proposed by Hainmueller, Hopkins, and Yamamoto (Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto.2014). The use of a conjoint experiment was chosen for its ability to capture the complex trade-offs individuals make when evaluating housing policy options while keeping the cognitive load within reasonable boundaries. Unlike traditional survey methods, which may only allow respondents to express general attitudes, conjoint experiments present participants with a set of realistic, multidimensional choices, where individuals must weigh multiple competing factors. By randomizing the levels of each attribute, the experiment enables us to identify causal relationships between specific policy features and public support, which would be challenging to achieve with traditional survey techniques. This approach enables us to uncover how different policy attributes interact to shape preferences, offering a more nuanced understanding of the factors that are most important to residents, while allowing us to study preferences across different population subgroups as well.

Table 1. Attributes and attribute levels of the conjoint experiment

Figure 1 presents a single conjoint table with fully randomized attribute levels displayed online to respondents. This design enables us to identify the causal effects of the seven policy components on the acceptance of housing densification.Footnote 2 Following the experiment, respondents proceeded to the second part of the survey, which included items on their sociodemographic details, political attitudes, and living environments.

Figure 1. A single conjoint table with fully randomized attribute levels as displayed online to respondents.

Stated acceptance

To investigate who accepts housing densification and to test the hypotheses derived from three strands of opposition in the urban development literature, we employed a survey item that asked respondents to self-report their general acceptance or policy support for housing densification on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (always refuse) to 7 (always accept).Footnote 3 Given the ordered structure of the 7-point scale item as dependent variable, we fit ordinal logistic regression models. In line with our theoretical expectations, we regress relative housing costs, settlement type, and left-right self-positioning on housing densification acceptance, described in greater detail below. Additionally, we control for associations with education, gender, homeownership, log-transformed monthly gross household income, and geocoded population density at the political commune level, age, and language to account for Switzerland’s cultural heterogeneity in the models. We employ both forward and backward selection of control variables, aiming for minimal values of the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) to assess model quality.

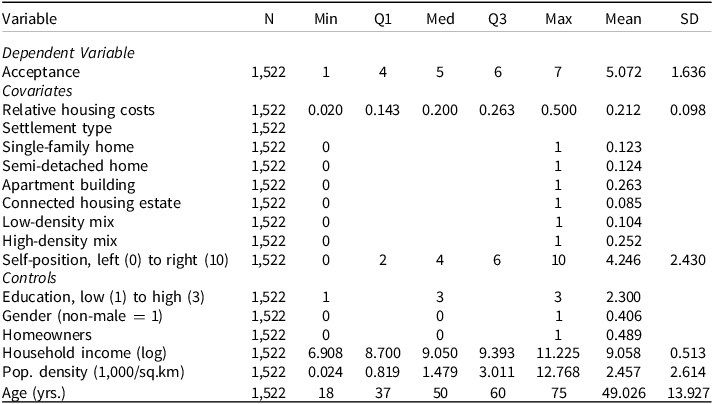

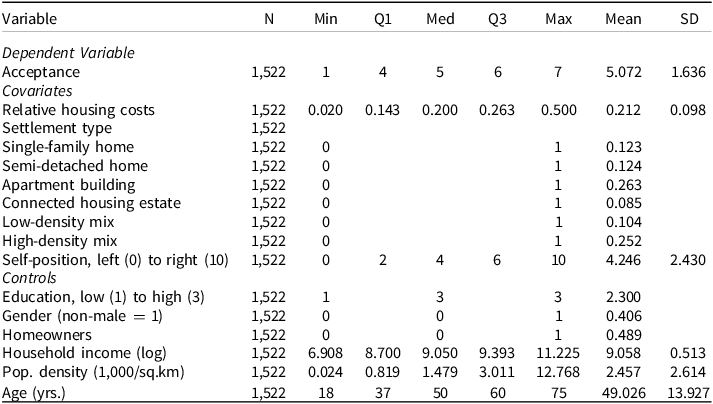

Using complete case analysis, the sample for the first analysis resulted in N = 1523. Table 2 presents summary statistics for the dependent variable, the three key parameters of interest described below, as well as for the control variables. Acceptance of housing densification is slightly skewed to the right, with “Mostly accept” being the most frequently selected level. The first covariate, relative housing costs, represents the share of monthly gross household income spent on housing. We use relative housing costs to standardize for high incomes and housing costs in Switzerland, to provide a more intuitive, comparable quantity, as well as to control for local income effects and their association with housing costs. In the sample, housing costs on average account for 21.2% of gross household incomes.Footnote 4 The higher the relative housing costs, the more we expect respondents to be affected by housing unaffordability.

Table 2. Summary statistics for the dependent variable, three key parameters of interests, and for six control variables

Settlement type pertains to a survey item that asks respondents to categorize their current homes into six descriptive settlement types, each representing varying degrees of built density. Single-family homes represent the lowest density and single usage, while high-density mixed-use areas refer to urban districts with diverse functions.Footnote 5 We anticipate a sorting effect in attitudes towards built density based on residency choice, with individuals residing in low-density settlements being less likely to accept housing densification.

Left-right self-positioning is measured using an 11-point scale, where respondents assess their political orientation in relation to the terms “left” and “right.” A score of 0 indicates the strongest leftist position, while a score of 10 represents the strongest position on the political right. Overall, the distribution is slightly skewed to the left, with a median of 4 and a mean of 4.271. Based on previous evidence, we anticipate that individuals identifying with the political right will be less likely to accept housing densification.

Experimental behavior

Turning to the empirical evidence from the conjoint experiment, 3,497 respondents completed four iterations of the conjoint experiment, resulting in a final sample of 27,976 observations. To provide an interpretable quantity for this evidence, we use average marginal component effects (AMCEs) (Hainmueller, Hopkins, and Yamamoto Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto.2014). AMCEs represent the effect of an attribute level measured against another level of the same attribute while holding other attributes constant (Bansak et al. Reference Bansak, Druckman and Green2021, p. 29). Thus, AMCEs can be understood as a summary measure of the overall effect of an attribute, accounting for the potential effects of other attributes by averaging the variations in effects they cause (Bansak et al. Reference Bansak, Druckman and Green2021, p. 29). Table 1 lists all attributes and attribute levels used for randomization in the conjoint experiment.

Stated and experimental behavior

AMCEs represent an attribute’s average across individual-level causal effects, which are relational quantities. The choice of the baseline category becomes a concern when investigating treatment heterogeneity. Some attributes may exhibit strong effects on certain respondents while having no effect on others – nuances that AMCEs fail to capture (Bansak et al. Reference Bansak, Druckman and Green2021). To further investigate subgroup heterogeneity, we turn to marginal means (MMs) as our quantity of interest. MMs, as proposed by Leeper, Hobolt, and Tilley (Reference Leeper, Hobolt and Tilley.2020), reflect the average choice of respondents within each subgroup for a specific attribute level. However, MMs are not comparable across different attribute levels. We use the findings from the first part of the analysis to effectively split the sample into groups and compute marginal means from the conjoint data to investigate subgroup heterogeneity.

Analysis

As described above, our analytical approach consists of three steps. The following sections will first show the analysis of stated acceptance before turning to the experimental evidence. Finally, we compare the stated behavior against the experimental behavior to investigate subgroup variance.

Analyzing stated acceptance

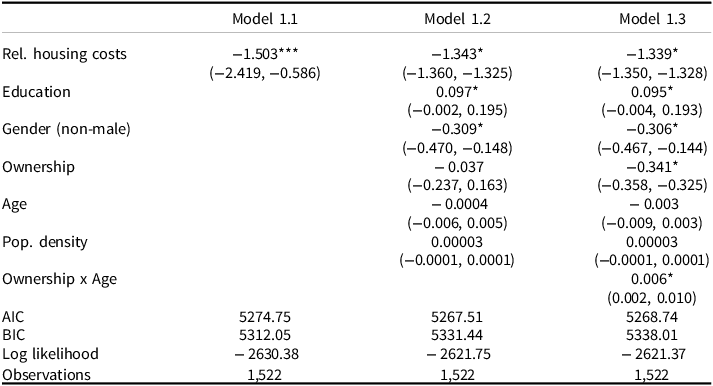

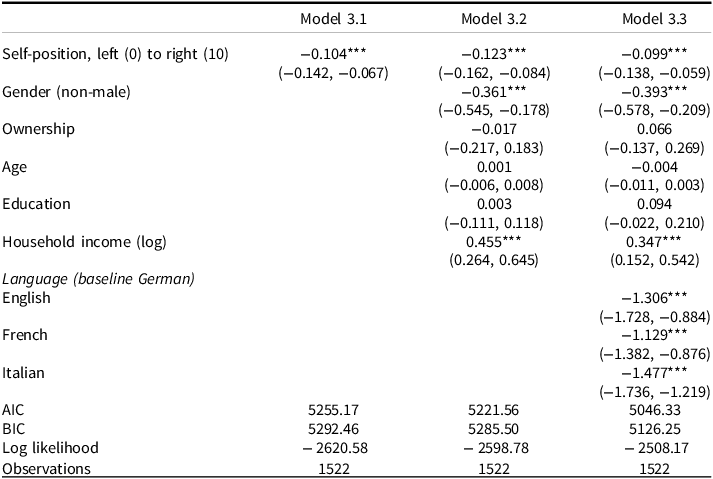

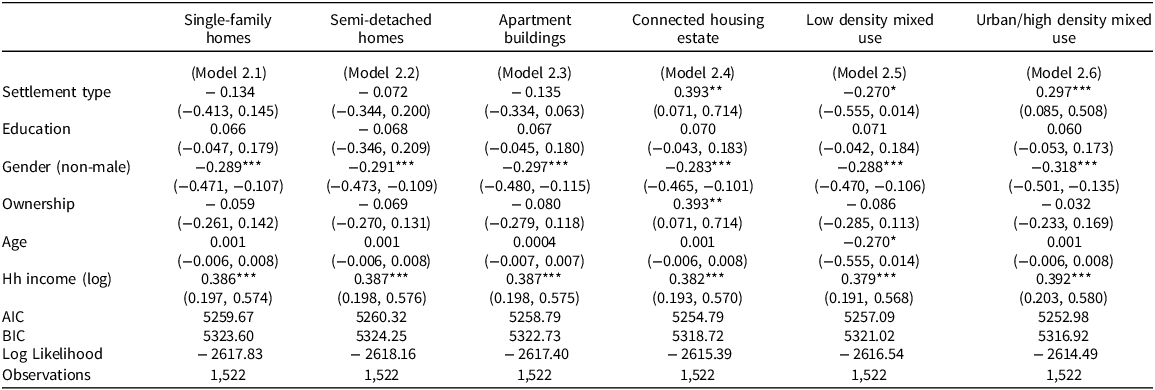

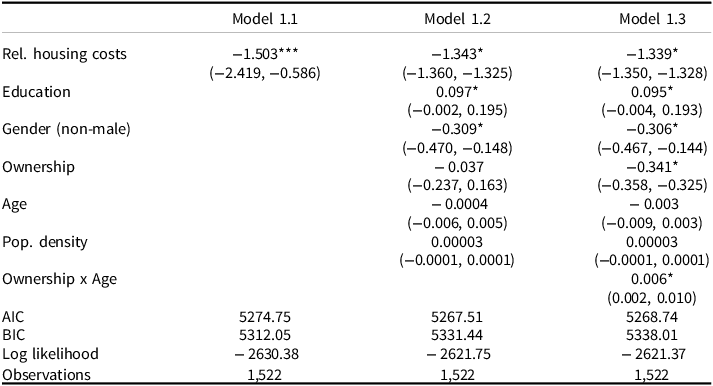

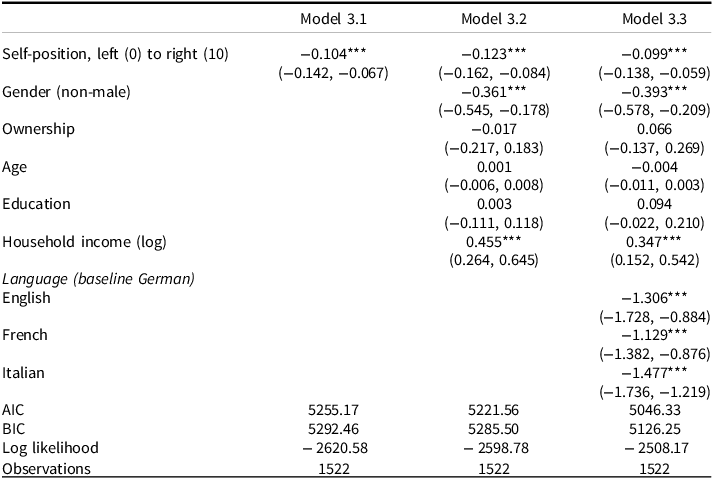

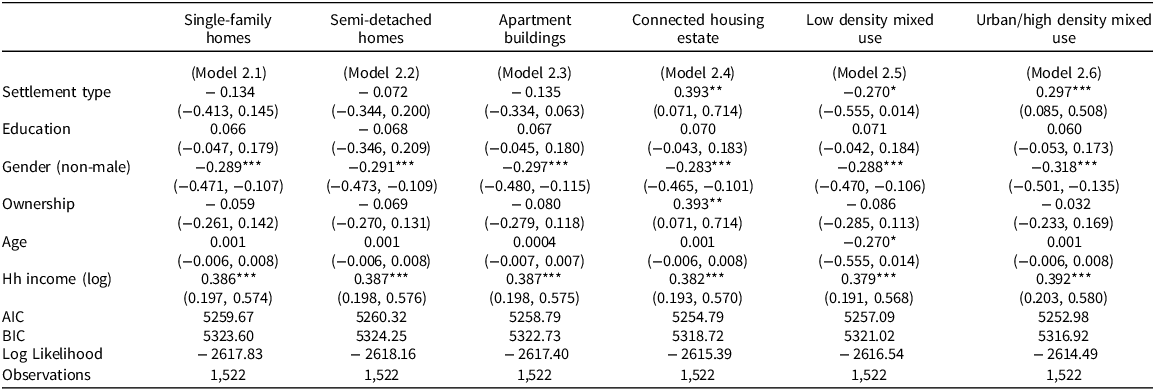

Tables 3, 4, and 5 display iterative ordinal logistic regression models of the acceptance item, with coefficients on the logarithmic odds scale. In each table, the first model of each iteration presents a baseline model with the respective key parameters of interest, before adding further covariates to improve model fit. All presented models successfully passed Brant tests for the parallel or proportional regression assumption (Brant Reference Brant1990; Schlegel and Steenbergen Reference Schlegel and Steenbergen.2020).

Table 3. Ordinal logistic regression output for relative housing costs on acceptance

Note: Log. odds displayed with 2.5% and 97.5% CIs in parentheses *p<0.1; **p<0.05; ***p<0.01 Iterative ordinal logistic regression models examining the effect of relative housing costs on the acceptance of housing densification. The findings highlight that individuals facing higher housing costs relative to their household income exhibit lower support for densification policies, aligning with the article’s theoretic expectation.

Table 4. Ordinal logistic regression output for left-right self-position on acceptance

Note: Log. odds displayed with 2.5% and 97.5% CIs in parentheses *p < 0.1; **p <0.05; ***p < 0.01 Iterative ordinal logistic regression models examining the effect of political left-right self-position on the acceptance of housing densification. The findings highlight that individuals self-identifying with the political right exhibit lower support for densification policies, aligning with theoretical expectations of ideological divides in housing preferences.

Table 5. Ordinal logistic regression output for settlement type on acceptance

Note: Log. odds displayed with 2.5% and 97.5% CIs in parentheses *p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01 Ordinal logistic regression models using dummy-variables for each settlement type and examining the effect of perceived neighborhood density on the acceptance of housing densification. The findings suggest that individuals who perceive their neighborhood as less dense are less likely to accept housing densification, suggesting an association between settlement structure and individual preferences.

Table 3 presents results for the first theoretical expectation, which examines whether acceptance of housing densification is less likely among individuals facing higher housing costs. Consistent with this expectation, we find that housing costs relative to monthly gross household income are negatively associated with acceptance across all model specifications. This relationship remains robust through two additional model iterations: the first introduces control variables typically associated with housing costs (Model 1.2) and the second further controls for the interaction between age and homeownership, as homeownership often correlates with age (Model 1.3). In this latter model, the fit improves marginally according to the log-likelihood measure, while both AIC and BIC decrease. Overall, the results indicate that the likelihood of acceptance is lower among individuals who face higher relative housing costs.Footnote 6

To investigate the second theoretical expectation – whether acceptance of housing densification corresponds with the geo-spatial ordering of individuals into settlement types – Table 4 displays separate regression results for settlement type, which have been collapsed into dummy variables for each category. The results indicate positive associations for connected housing estates (e.g. housing cooperatives) and urban high-density mixed-use developments, while all other categories exhibit negative associations. This indicates that individuals who perceive their living environment as denser are more likely to accept housing densification, suggesting an association between settlement structure and individual preferences.Footnote 7 By replicating the model and substituting settlement type with an index measuring neighborhood attachment, the results presented in Table A5 in the Appendix indicate that respondents who feel a stronger attachment to their neighborhoods are more likely to accept housing densification. This finding contrasts with the prevailing literature, which typically suggests that the effect is in the opposite direction.Footnote 8

The regression results for the third theoretical expectation – acceptance of housing densification is less likely among right-leaning individuals – are presented in Table 4. The negative coefficients associated with self-positioning on housing densification acceptance indicate that the likelihood of acceptance diminishes as individuals align themselves further to the political right, thus supporting our theoretical expectation. Table A3 in the Appendix illustrates that this relationship remains robust when alternative measures, such as self-positions on redistribution, climate change, migration, and regulation, are used instead of the left-right dimension. Across all specifications, the probability of accepting housing densification decreases as individuals adopt positions typically associated with the political right.Footnote 9

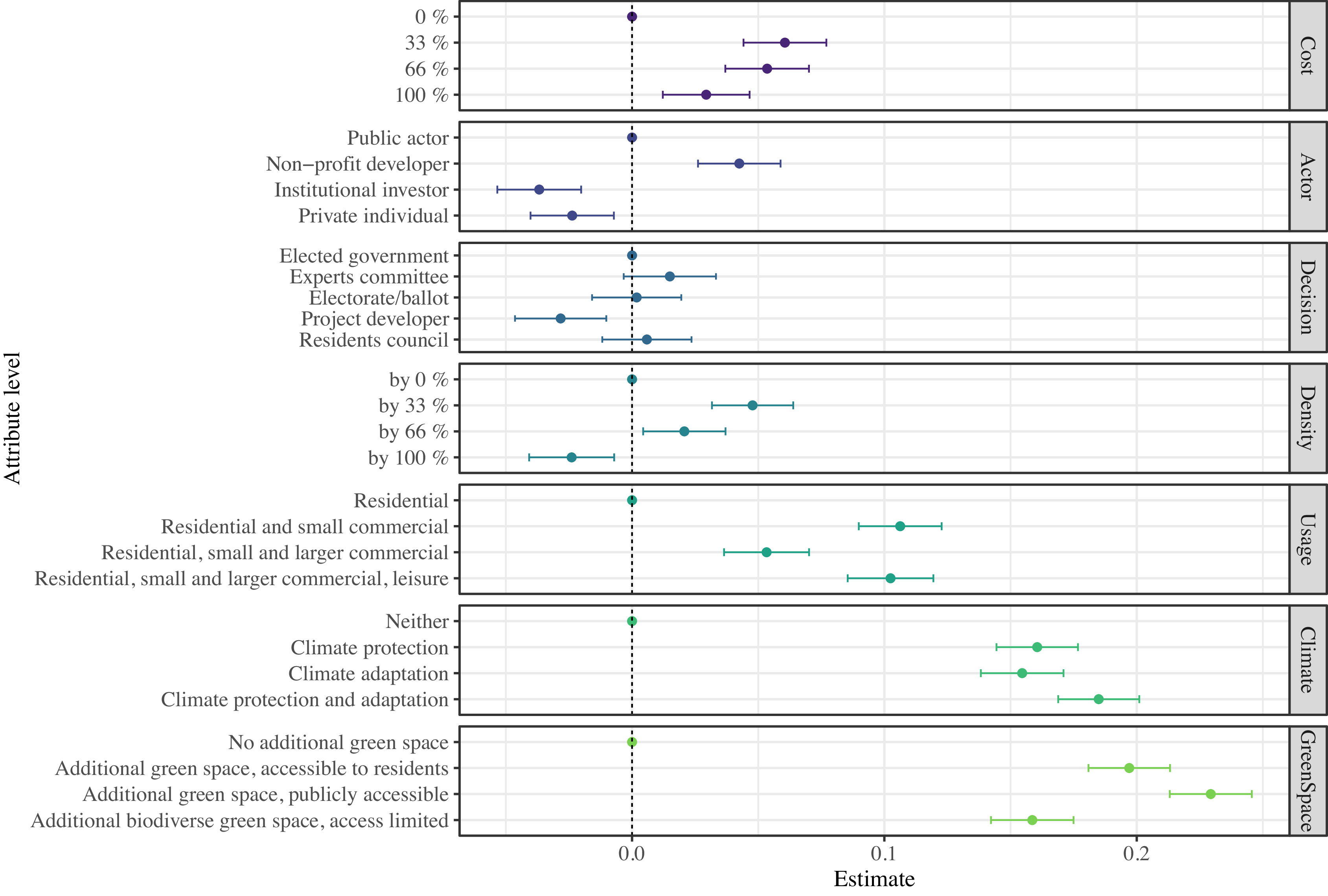

Analyzing experimental behavior

To interpret the experimental data, Figure 2 presents the AMCEs for our full survey sample across all attribute levels, displaying 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using the first mentioned attribute level as the baseline. Our outcome measure is based on a choice item that asks respondents to indicate their preference between two proposals. Averaged across the entire sample, the AMCEs indicate significant preferences for all levels of cost rent compared to no cost rent, non-profit developers over institutional investors and private individuals, as well as public actors, decision-making by the project developer, moderate increases in population density, mixed usages over residential usage only, any climate measure, and more accessible green space.

Figure 2. Average marginal component effects with 95% CIs, first attribute set as baseline.

Interestingly, the attributes related to the environment demonstrate the largest effects across the sample. The results for cost rent, actors, and decision-making indicate a preference against market-oriented housing development. There are significant positive effects associated with the provision of cost-rent housing and non-profit actors, while decision-making by project developers is disfavored.

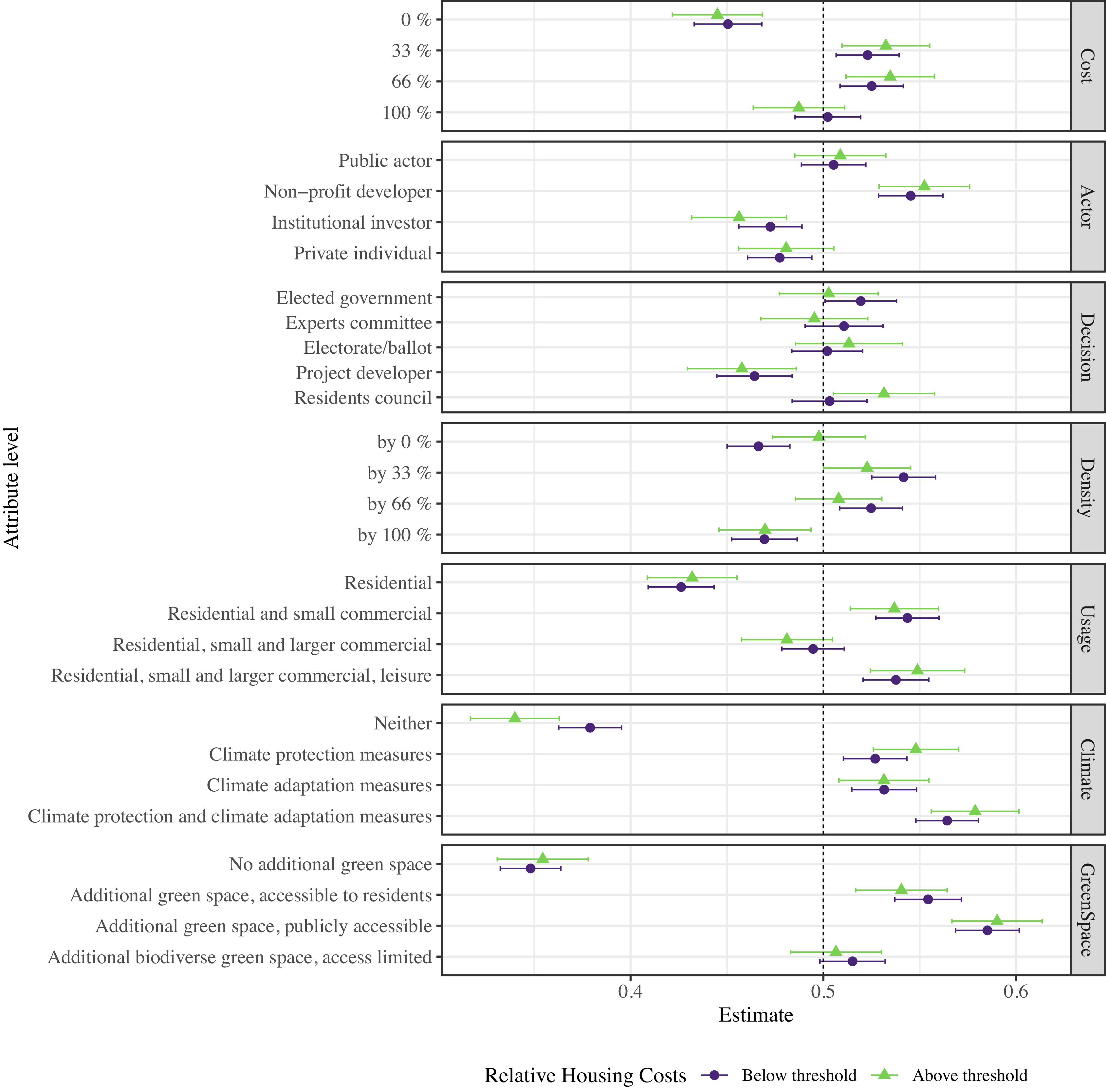

Bringing stated and experimental behavior together

By presenting marginal means, we illustrate the average choice or preference of respondents across attribute levels. A critical observation is the overlap of confidence intervals within these attribute levels. When these confidence intervals overlap horizontally, it indicates that there is no statistically significant variation in preferences among the considered subgroups. Such overlaps can offer valuable insights into the robustness and generalizability of our findings across different respondent profiles.

When the sample is divided into two groups based on the affordability cut-off for relative housing costs, Figure 3 reveals no meaningful differences between the groups, except for the attribute level that proposes no climate measures.Footnote 10 Thus, the preferences identified in Figure 2 are not driven by underlying economic motivations but are relatively homogeneously distributed among Swiss urban residents.Footnote 11

Figure 3. Marginal means for two housing costs based on housing affordability groups on the probability of proposal choice with 95% CIs. Those above the threshold face housing costs considered unaffordable in relation to their gross household income.

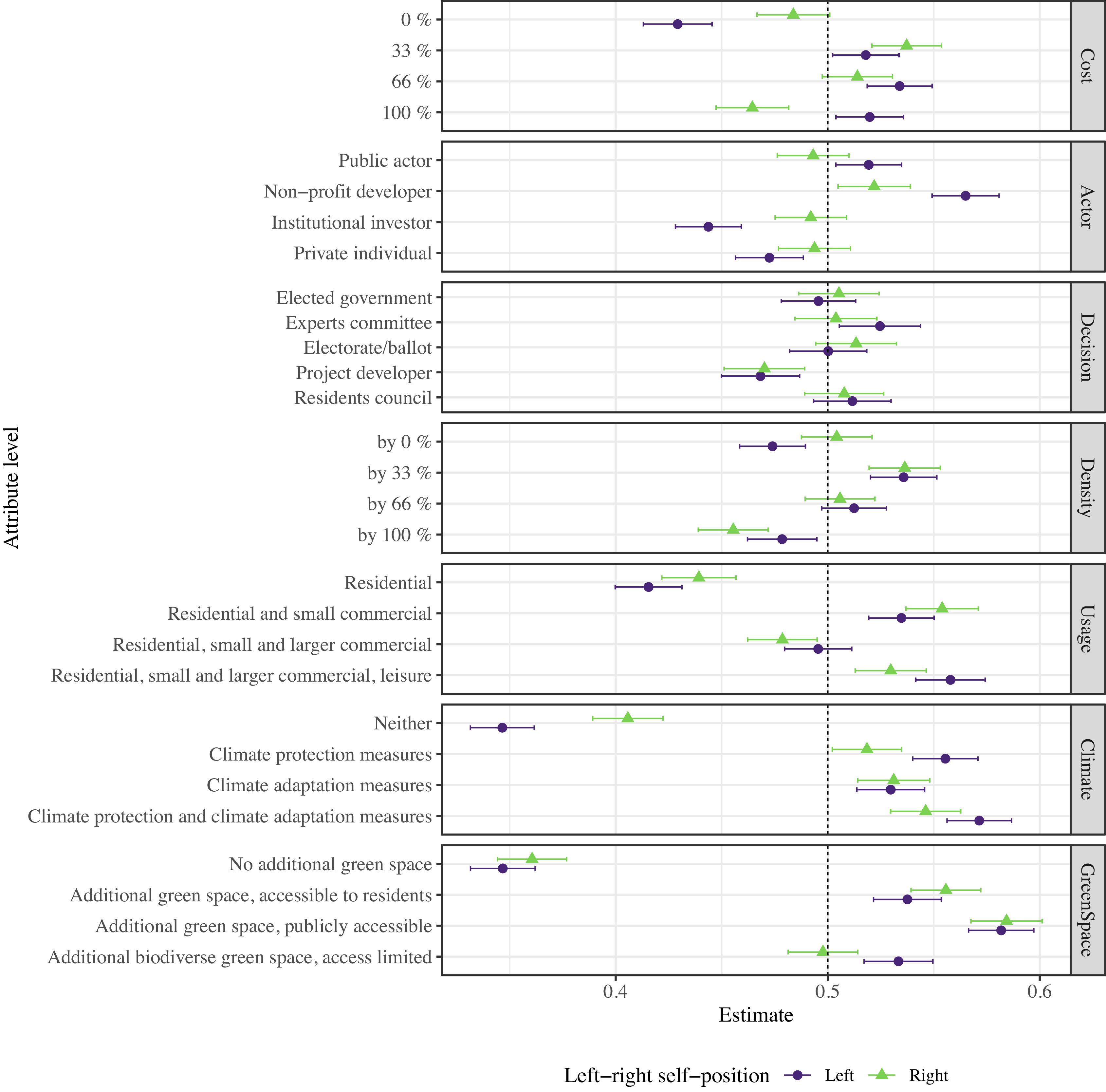

While dividing the sample based on low and high self-perceived neighborhood density reveals no significant differences between the groups (see Figure A1 in the Appendix), a split along the median of the 11-point left-right self-positioning scale provides more insightful results. Figure 4 illustrates that acceptance of housing development aligns more closely with broader ideological patterns. Here, left-leaning individuals penalize the absence of cost-rent housing, while right-leaning individuals exhibit near indifference. This trend reverses when only cost-rent housing units are provided, as right-leaning individuals tend to reject this measure, whereas left-leaning individuals express support for it. Furthermore, the preferences for non-profit developers and against institutional investors, as shown in Figure 3, are influenced by this partisan divide, with the effects being more pronounced among left-leaning individuals compared to their right-leaning counterparts. In contrast, preferences regarding decision-making, density, and usage attributes are relatively consistent across both groups.

Figure 4. Marginal means for two ideological groups on probability of proposal choice with 95% CIs.

On the ecological dimension, group differences become apparent once more. Regarding the climate protection/adaptation attribute, both groups reject the absence of climate measures; however, right-leaning individuals are less likely to reject this option than their left-leaning counterparts. For the climate adaptation attribute, we connected the level description to the environmental impact within the local context (the neighborhood), while the protection measure emphasized emission compensation, reflecting a more global perspective on anthropogenic climate change. As expected, we observe statistically significant differences between left-leaning and right-leaning individuals concerning climate protection issues, while the MMs for climate adaptation do not differ between the two groups. When both measures are presented together, group differences re-emerge, although they do so at statistically insignificant levels. A second measure related to ecological concerns is the green space attribute. Here, we observe no significant differences between the groups, except for the level that describes additional green space designated for non-human use, framed as a biodiversity measure. Here, right-leaning individuals demonstrate a lower probability of accepting this measure compared to their left-leaning counterparts.

Discussion of main findings

To better understand opposition to housing densification in Swiss cities and towns, we undertook a three-step analytical approach, combining and integrating the results of two separate analyses into a third step. The following section discusses the results of the analyses, reflecting on their implications for urban planning and policymaking in the Swiss context.

A reoccurring pattern in the findings is the association between redistributive, cost-related factors, and acceptance of housing densification. For instance, the probability of accepting densification projects is lower among individuals facing high relative housing costs. Furthermore, the experimental evidence reveals a clear preference among all respondents for the provision of cost-rent housing and for non-profit developers. This may reflect a broader public demand for affordable housing and a perception that non-profit developers are more closely aligned with community interests. Furthermore, preferences regarding decision-making in housing projects favor democratic processes over those led by project developers across all differentiated groups, a finding consistent with other research (Monkkonen and Manville Reference Monkkonen and Manville.2019). This identified pattern remains robust regardless of respondents’ experience with housing unaffordability and their self-perceived neighborhood density. Hence, the evidence suggests that a broad coalition, sensitive to the redistributional effects of housing policy, accepts and supports densification when intended as a measure to combat housing unaffordability. This suggests that public opposition often targets how densification is implemented, particularly when it is perceived as profit-driven or exclusionary, rather than rejecting densification as a principle (Debrunner Reference Debrunner2024; Debrunner and Kaufmann Reference Debrunner and Kaufmann.2023; Kaufmann et al. Reference Kaufmann2023).

The findings further underscore the ongoing politicization of urban development, with housing densification emerging as a central issue in urban politics. Our results demonstrate that political orientation has a significant and robust effect on the acceptance of housing densification, as anticipated. The initial analysis indicates that right-leaning individuals are generally less likely to accept densification. However, Figure 4 reveals that this partisan divide is more pronounced for some policy characteristics while being negligible for others. Preferences regarding decision-making, density increases, usage types and the provision of additional green space are relatively evenly distributed. In contrast, measures that are more closely related to cost considerations, market externalities, or profit orientation (e.g., cost-rent housing, involved actors) exhibit significant differences between the two groups. While we initially expected these differences to be primarily driven by exposure to housing unaffordability, the empirical evidence indicates that the ideological dimension significantly influences preferences regarding housing policy characteristics, likely driven by general preferences for redistribution and governmental intervention.

A second pattern emerges in the environmental dimension of urban development. The experimental data not only demonstrates the largest effects on attributes related to climate measures and green space but also reveals the most significant differences between groups. We find that climate protection or mitigation measures have varying effects on left-leaning and right-leaning individuals, consistent with our theoretical expectations and likely a politicization effect. Right-leaning individuals appear to penalize measures framed as climate mitigation at the global level, particularly those that use the term “biodiversity.” This observation aligns with other research indicating that conservatives are more likely to support environmental protection measures when they are framed as local issues or when they yield positive outcomes at the local level, rather than on a broader or global scale, as suggested by the term “biodiversity” (Bayes and Druckman Reference Bayes and Druckman.2021; Druckman and McGrath Reference Druckman and McGrath.2019; Deslatte Reference Deslatte2023). Interestingly, the relatively straightforward design of the experiment allowed us to highlight these differences in preferences for certain measures and to examine group differences based on the contestation of climate change.

Despite these differences, the overall trend we observe is a widespread acceptance of densification. Increases in population density are almost unanimously approved, suggesting a public willingness to accommodate urban growth. Concurrently, there is a clear demand for developments that incorporate recreational, communal, and green spaces aimed at enhancing the quality of urban life and community well-being. This raises an important and broader question: how can we effectively densify urban areas?

Conclusion

In this article, we examined urban residents’ attitudes and behaviors towards housing densification in a direct democratic and renter-dominated urban context. Drawing on new experimental survey data from a diverse range of urban environments, including small and medium-sized towns as well as larger globalized cities, we found that acceptance of housing densification is lower among individuals facing high housing costs, those who perceive their neighborhoods as low-density, and individuals who self-identify as politically right-leaning. The article highlights clear preferences in policymaking for cost-rent models, non-profit developers, moderate increases in population density, mixed-use developments, climate measures and additional green space. However, these patterns are not uniformly distributed and reveal important group differences. Overall, the article emphasizes the socio-economic and environmental implications of urban development and the considerable influence of planning and policymaking in shaping the behavioral patterns associated with housing policy.

The findings of this study contribute to the re-emerging research on housing politics. Contrary to our theoretical expectations, we observe that respondents behave relatively uniformly in the experiment, regardless of their exposure to housing unaffordability, suggesting a broad public consensus on the need for affordable housing. In contrast to the Anglo-Saxon “ownership society” (Ansell et al. Reference Ansell2022), the Swiss renters’ society – characterized by high financial stability, elevated income levels, a strong social welfare state, and high-quality rental stock – results in a diminished need for individuals to protect themselves individually against financial and other risks considered mitigated by homeownership. Thus, the observed consensus could reflect a shared understanding of solving housing issues collectively, even or especially in times of affordability crises, usually making individuals less supportive of collective action on housing policy (Cansunar and Ansell Reference Cansunar and Ansell.2021). The remaining differences we observe among various subgroups of urban residents could then rather be artifacts from the politicization of housing densification, particularly in relation to political conflict on the environmental and socio-economic dimensions.

On epistemological grounds, the research design allowed us to uncover a potential fallacy in public opinion regarding housing policies. While we find residents of single-family homes to state a lower likelihood of accepting housing densification compared to resident of urban high density mixed-use areas, the differences disappear in the experimental behavior of both groups. This finding aligns with scholarly discourse indicating that behaviors do not always reflect corresponding opinions, as observed in other policy fields (Bastian and Loughnan Reference Bastian and Loughnan.2017). Thus, simple opinion polls based on stated opinions are likely to underestimate acceptance of housing densification, to disguise a generally higher level of policy acceptance, or even introduce sampling bias. This would then become problematic where stated public opinion is introduced as an argument against the feasibility of policy proposals to public and policy discourses.

These results have important practical implications. Currently, political and market actors in Switzerland tend to view the housing crises as a problem stemming from overly strict regulations that hinder the housing market’s ability to supply adequate housing. However, the article’s empirical evidence reveals significant preferences among Swiss urban residents for measures that address housing unaffordability including preferences for more governmental intervention and market regulation based on a nuanced understanding of both the socio-economic and ecological dimensions of housing development. This links the article’s findings to a more critical perspective on housing densification and exemplifies “[…] the shallow idea that the housing question comes down to determining the right balance between state and market. […] State action can be used to democratize and redistribute housing, or it can function to preserve inequality and support private profitmaking [sic].” (Marcuse and Madden Reference Marcuse and Madden.2016, p. 144).

Nonetheless, the results face limitations. Methodologically, the use of different scales for our key parameters at the individual level prevents us from quantifying which strand of literature most effectively explains opposition to housing densification. Additionally, the experimental design imposes narrow boundaries on the expression of preferences, reflecting the status quo of the Swiss housing market. As markets often conflate true preferences, respondents may be making choices within current market practices based on a lesser-evil approach. Beyond these limitations, and to address the contingency of single cases, we emphasize that future research could adopt a comparative approach to account for heterogeneity across different contexts and develop a coherent typology for situating cases within the “varieties of housing capitalism” (Ansell Reference Ansell2019, p. 171). By considering institutional influences on housing policy and regulation, or policy styles, researchers could enhance the robustness of theory development and improve the overall understanding of attitudes and behaviors stemming from these varieties. This approach could also increase the accountability and responsiveness of decision-makers involved in urban development.

Overall, the re-emergence of the housing issue in public, policymaking, and scholarly discourses is significant. Similar to many other European cities, social movements advocating for affordable housing are gaining momentum in Swiss cities. For policy-makers concerned about social cohesion, this represents a critical juncture. Additionally, Switzerland’s direct-democratic system offers a unique perspective, as citizens have the ability to directly influence housing policy, providing valuable insights into how democratic participation can shape urban planning in more responsive and inclusive ways. The empirical evidence presented in this study indicates potential pathways for policymaking while highlighting the place-based specifics of heterogeneous urban spaces, particularly in smaller communities (Kumar and Stenberg Reference Kumar and Stenberg.2023). It also underscores the distributional and social consequences of housing densification and, although not explicitly testing for it, points in the direction that NIMBYism – often referred to as main explanation for opposition to housing densification – might mask residents’ broader considerations of housing equality during times of housing unaffordability and rising ecological concern. Our findings suggest that to effectively implement urban densification, future housing policy should align stronger with the needs of local residents and prioritize affordable housing and ecological measures.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X25100883.

Data availability statement

Replication materials are available in the Journal of Public Policy Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/I40Q2E. Replication materials (including the survey and conjoint data, full R-files to replicate all analyses presented in the article and supplementary materials) will be made available in the Journal of Public Policy Dataverse upon acceptance.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Martin Vinæs Larsen, Gracia Brückmann, Jake Stephan, Stefan Wehrli, Patricia Wäger, and Manuel Widmer, participants at presentations at the Swiss Political Science Annual Congress 2023 and the 2023 D-A-CH-Congress, as well as members and students of IRL at ETH Zurich for survey pretests and early-stage presentations. The authors thank Cambridge Proofreading LLC for providing proofreading support preparing the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Funding statements

This research was supported by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation under grant number 200499.