Introduction

Over the past decades, the world’s seabird populations have declined drastically due to multiple threats, such as the introduction of exotic species into breeding sites, incidental mortality in fishing gear, pollution and the loss of nesting habitats (Croxall et al. Reference Croxall, Butchart, Lascelles, Stattersfield, Sullivan, Symes and Taylor2012). Actions to protect seabirds include best-practice guidelines to reduce incidental mortality in fisheries, and eradication of invasive species at nesting sites (Donlan and Wilcox Reference Donlan and Wilcox2008, Melvin et al. Reference Melvin, Guy and Read2013). The protection of breeding sites is a priority action, as well as studies on population trend for analysing population dynamics (Croxall et al. Reference Croxall, Butchart, Lascelles, Stattersfield, Sullivan, Symes and Taylor2012).

Herein, we report the current population status of a seabird nesting on several islands with different levels of protection, the Peruvian Diving-petrel, Pelecanoides garnotii. This species is endemic to the cold, nutrient-rich waters of the Humboldt Current System, distributed between 5°S and 37°S (Warham Reference Warham1990, Luna-Jorquera et al. Reference Luna-Jorquera, Simeone, Aguilar and Bozinovic2003), and thus breeding colonies are found only in Chile and Peru. The Peruvian Diving-petrel was one of the most abundant and widely distributed seabirds of the Humboldt Current System during the early 1900s (Murphy Reference Murphy1936). Perhaps the largest colony was that of Chañaral Island estimated in 1944 as ∼200,000 individuals and presumably extirpated due to the introduction of foxes (Araya and Duffy Reference Araya and Duffy1987). Since 1994, the species has been globally categorised as ‘Endangered’ because its breeding range is limited to six islands, and its subpopulations are declining (BirdLife International 2019). The major current threats are illegal guano extraction, bycatch, introduced species, and poor conservation of breeding sites (Simeone et al. Reference Simeone, Luna-Jorquera, Bernal, Garthe, Sepúlveda, Villablanca, Ellenberg, Contreras, Muñoz and Ponce2003, Luna-Jorquera et al. Reference Luna-Jorquera, Fernández and Rivadeneira2012). However, current and reliable estimates of the breeding population size in Chile are not available, hindering the implementation of protection measures for the existing colonies. Our aim here was to estimate the current breeding population of the Peruvian Diving-petrel in Chile. We surveyed all the existing Chilean colonies and collected past historical estimates that, in combination with our data, were used to analyse both the current Chilean number of breeding pairs and the population trend of the adult breeding on the main Chilean colony.

Methods

Study area

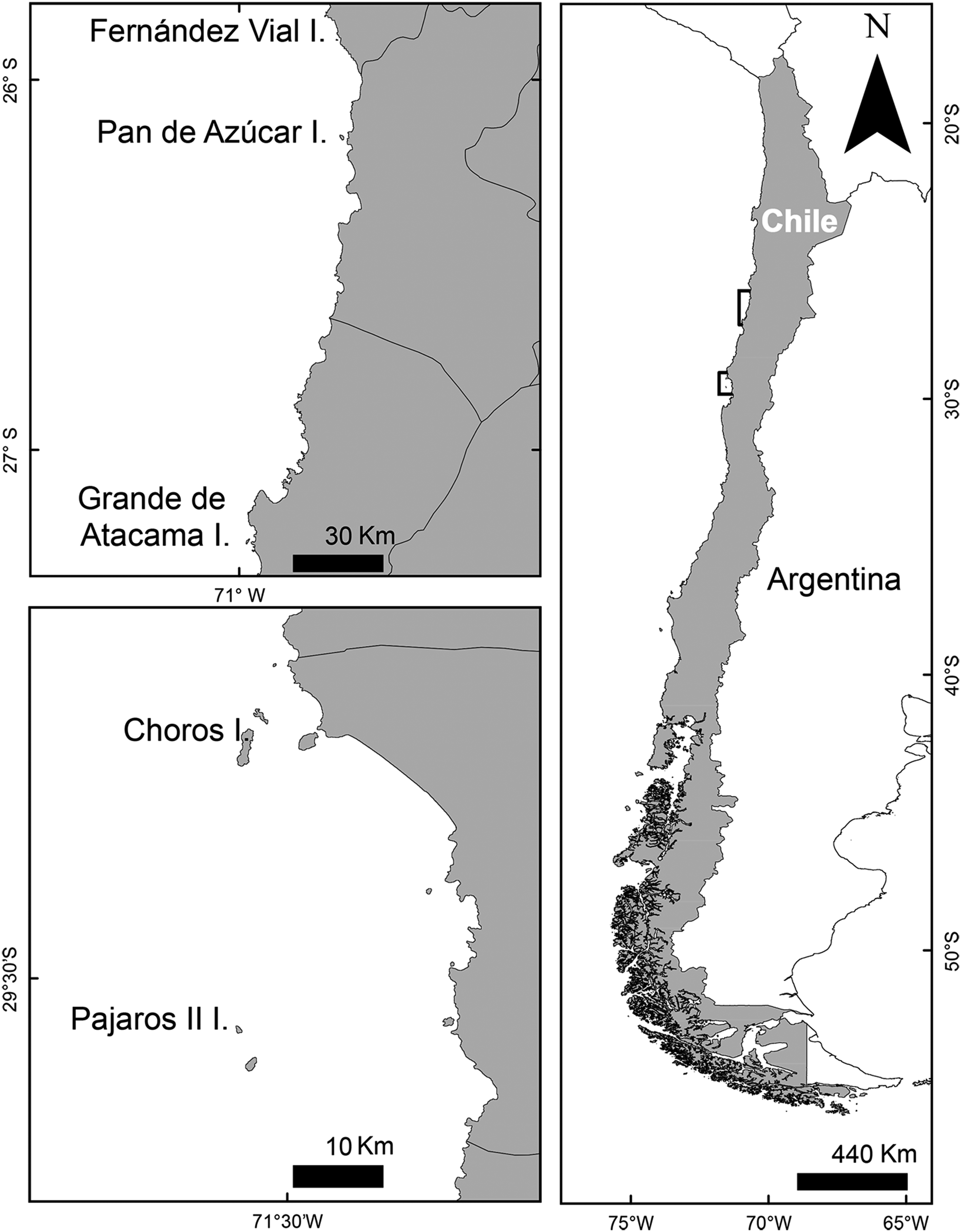

There are four main diving petrel colonies in Chile, located between Pan de Azúcar Island in the Atacama region, to Pájaros II Island, in the region of Coquimbo (Figure 1, Table 1). Two islands are located in the Atacama region where a desert climate prevails (Di Castri and Hajek Reference Di Castri and Hajek1976), while the other two islands in Coquimbo have an arid to semiarid Mediterranean climate (Novoa and López Reference Novoa, López, Squeo, Arancio and Gutiérrez2001). Pájaros II Island is the southernmost reproductive colony of the Peruvian Diving-petrel, but unlike other islands is not legally protected (Simeone et al. Reference Simeone, Luna-Jorquera, Bernal, Garthe, Sepúlveda, Villablanca, Ellenberg, Contreras, Muñoz and Ponce2003). In 1985, Pan de Azúcar Island became part of a national park. In 1990 and 2004, Choros Island and Grande de Atacama Island, respectively, were legally protected (Vilina et al. Reference Vilina, Capella, González and Gibbons1995, Simeone Reference Simeone1996, Squeo et al. Reference Squeo, Arancio and Gutiérrez2008). A fifth breeding site, not included in the surveys, is Fernández Vial Islet that holds eight breeding pairs (Guerra-Correa et al. Reference Guerra-Correa, Guerra-Castro and Paez2011).

Figure 1. Distribution map of coastal islands with confirmed breeding colonies of Peruvian Diving-petrel.

Table 1. Coastal Island of Northern Chile with confirmed colonies of Peruvian Diving-petrel. Protection category (PC), management plan (MP) and accessibility to the island are given. DM is the distance to the mainland.

Population estimates of Peruvian Diving-petrels

The data obtained in this study came from surveys conducted between 2010 and 2014 (Table S1 on the online Supplementary material). To estimate the number of breeders, we obtained data on the size of breeding patches (hereafter called “patches”), nest density, and occupancy rates from each patch. The patches on all islands were identified and georeferenced with a GPS (Garmin). On Choros Island, notably, a few patches of small size located mainly in the northern part of the island were not included in the study because they were on a slope and accessing them would have put the nests at risk. Patches with more than 10 burrows were georeferenced by walking around the perimeter to estimate the patch size. For all the islands, the patch sizes ranged from 3 to 5,752 m2 (Table 2 and Table S1). In patches of ≤ 59 m2 (n = 30), the number of nests was determined by direct counts carried out independently by two observers. The final value was the mean value of the observers when the differences between the two counts were equal or lower than 5%.

Table 2. Estimated reproductive pairs of Pelecanoides garnotii Diving-petrels in Chile.

In patches greater than 59 m2, a circular plot of 0.44 m2 was used to subsample. The use of a plot allows us to reduce errors stemming from double counting, and to calculate the 95% confidence interval, to determine how much variation in results to expect from sample to sample, and the accuracy of population estimates. After the patch area was measured, circular plots were placed in the centre and the periphery of each patch. In every patch, count points were systematically established by alternating centre/periphery every 20 steps to complete all the patch perimeter. At every count point, the circular plot attached to a rope was randomly thrown using 3 m length of rope for the periphery, and 10 m for the centre. A nest was included in the count when their entrance was entirely within the sampling plot. To obtain the sampling area for each patch, the area of the circular plot was multiplied by the number of times that was applied. The number of nests in the sampled area of every patch was calculated by summing the counts of nests registered every time the plot was applied. To estimate nest density, the total number of nests was divided by the total sampled area. The mean nest density and the 95% confidence interval were obtained from the sampled patches on each island.

Peruvian Diving-petrels build their nests in burrows and visit the colonies at night (Warham Reference Warham1990). Proper counts of nocturnal burrowing seabirds are difficult to obtain (e.g. Kennedy and Pachlatko Reference Kennedy and Pachlatko2012). Researcher access to burrowing petrel colonies is restricted to the periphery because nests are highly susceptible to collapse. Thus, burrow densities have been usually estimated by counting burrow entrance numbers in a delimited area of known size, and then multiplying the densities by the total area of the colony to obtain the estimated total number of nests (Warham and Wilson Reference Warham and Wilson1982). Our study is based on a similar principle, but we used an endoscopic camera to determine the occupation rate, and also to estimate the number of nests with more than one entrance to correct the occupation rate. The endoscopic camera with LED light (Sandpiper Technologies, Inc.) was used to determine the occupancy rate of 10 randomly selected nests per patch. Each nest was defined as one of five categories: (1) chick present, (2) adult present, (3) adult with egg, (4) adult with the chick, or (5) empty nest. The incubation chambers of the Peruvian Diving-petrel were not connected with other nests; thus, each nest was independent of all others. However, we determined that some nests had two or three entrances. The number of active nests (categories 1–4) of every patch were both corrected for the ratio between active/inactive nests, and the percentage of the nests with a double entrance. The ratio of the active/inactive nests was determined as the number of occupied nests among the total number of examined nests.

Trends of the breeding population of Peruvian Diving-petrels in Chile

Historical numbers of breeding pairs of Peruvian Diving-petrels in Chile were obtained from published and unpublished sources available from 1980 to 2009 (Table 3). In order to estimate the trends of breeding pairs, we performed a generalised additive mixed models (GAMM) using the poptrend function (Knape Reference Knape2016) available in R (R Core Team 2017). This function allows changes in the number of breeders to be expressed in a long-term nonlinear smooth component representing the prevailing trend for the colony (Knape Reference Knape2016). This analysis was conducted only for the birds breeding on Choros Island, for which it was possible to gather information for at least 10 years. We collated our data with those reported in several studies reporting the number of breeding pairs (see Table 3). The trend of breeding pairs was estimated using the function smooth and a quasi-Poisson distributional family of the response variable (i.e. the number of breeding pairs) with automatic selection of the degree of freedom. In fitting the smooth trend, the time was considered as random effects. A binary variable was included to indicate whether the counting of the reproductive pairs was obtained using our methodology or correspond to published data obtained with other methods. Visual inspection of residual plots did not reveal any apparent deviations from homoscedasticity or normality.

Table 3. Historical and present records of breeding pairs of Peruvian Diving-petrels Pelecanoides garnotii in Chile in several coastal islands in Northern Chile.

Results

Estimation of the reproductive population of Peruvian Diving-petrels

The size of the current reproductive population of the Peruvian Diving-petrel in Chile was estimated to be ∼12,500 breeding pairs (95% CI = 10,613–14,676). The greatest number of breeding pairs was on Choros Island, ∼95% of the Chilean breeding population, followed by Pan de Azúcar, and Grande de Atacama islands (Table 2). On Grande de Atacama there were only two patches of diving petrels, and both were < 59 m2. A high number of empty nests were found on Pan de Azúcar Island, many of them were collapsed or with cobwebs at the entrance. The highest nest densities were found on Choros and Pan de Azúcar islands (Table 2 and Table S1).

From 2010 to 2014, a total of 61 breeding patches of diving petrels on Choros Island were measured, mainly in the south-western part of the island. Patch size ranged from 3 to 5,752 m2. The estimated nest density during the study period ranged from 0.47 to 1.50 nests m-2 with a mean density of 0.89 nests m-2.

According to our study, at Choros Island the reproductive period began in early September and markedly decreased in February and March, although breeding adults were recorded between April and August during 2014. The reproductive peak occurred during spring (Figure 2). In general, a nest entrance corresponded to one incubation chamber (∼96%; 1,459 nests surveyed), and only ∼4% presented two or three nest entrances. During the reproductive peak, ∼60% of all nests per patch were found to be active. Towards the end of the breeding season, the occupancy rate was about 4% of active nests.

Figure 2. Inactive and active nest occupancy of Peruvian Diving-petrels during spring, summer, autumn, and winter in patches on Choros Island.

Historical trends of the breeding population of Peruvian Diving-petrels in Chile

The overall breeding population trend of Peruvian Diving-petrels had gradually increased over time since 2008 (Table 3 and Figure 3). The total number of breeding pairs recorded by year ranged from 75 (2001) to 12,031 (2013) (Figure 3). Pájaros II and Fernández Vial islands presented the lowest numbers of breeding pairs (Table 3). On Pan de Azúcar Island, the number of breeding pairs ranged from 220 to 520, except during 2009 when 3,317 breeding pairs were reported (Table 3). Grande de Atacama Island showed a range of 75 to 204 breeding pairs throughout the time.

Figure 3. The historical breeding population of Peruvian Diving-petrels for Chile during the spring reproductive peak. Estimates of total breeding pairs (numbers above each bar) for Chile are indicated by year and by island according to historical and present records. The islands considered are Choros, Pan de Azúcar, Grande de Atacama, Pájaros II and Fernández Vial islands.

Choros Island showed the highest number of breeding pairs over time, and its overall population trend displayed a rapid increase, reaching a maximum of 11,934 breeding pairs by 2013 (Figure 3). This tendency is confirmed by the modelling using GAMM (Figure 4). The estimated change in the number of breeding pairs shows a steady and significant (P < 0.001) increase from 1980 to 2014. The increase in the long-term component for the entire analysed period in Choros Island coincides with the tendency observed for the other colonies considered as a whole (see Figure 3). Between 2010 and 2014 the increase in breeding pairs on Choros Island was 43% (2.5%, 93% range of the 95% CI).

Figure 4. The estimated trend for the number of breeding pairs of the Peruvian Diving-petrel on Choros Island. The solid line is the estimated long-term component of the trend, and the points are estimates of the trend with estimates of the random year effects. Confidence intervals (shaded area and vertical lines) are computed from the 2.5% and 97.5% quantiles of the bootstrap distribution. The green colour of the solid line shows a significant increase in the trend at the 5% level. The green bottom rectangle shows that for the entire period, the curvature of the line trend is significantly positive

Discussion

Size and trend of the breeding population of Peruvian Diving-petrels in Chile

The total breeding population of Peruvian Diving-petrels in Chile had not previously been estimated. Breeding individuals can be found throughout the year, with only one reproductive peak that occurs during spring, contrasting with the colonies in Peru, where two reproductive peaks occurred during the year, from December to March and from May to September (Jahncke and Goya Reference Jahncke and Goya1998). Overall, during months of higher occupancy, ∼60% of all nests per patch were active. This is consistent with the occupancy rate of 58% estimated by Simeone et al. (Reference Simeone, Luna-Jorquera, Bernal, Garthe, Sepúlveda, Villablanca, Ellenberg, Contreras, Muñoz and Ponce2003) for the same main colonies of Choros Island.

Historical records of the breeding population of Peruvian Diving-petrel in Chile are scarce and scattered. For instance, for the protected Choros and Pan de Azúcar islands records date back to the 1980s (BirdLife International 1992), but between 1981 and 1998 no new estimations were made. Except for recent estimates made at Choros Island, there is no regular monitoring of the Peruvian Diving-petrel colonies, which makes it difficult to determine the general trend for the species in Chile. Here we estimated the trend for the number of breeding pairs nesting on Choros Island that increased from 300 in 1980 to 10,789 in 2014, with a maximum of 11,934 pairs in 2013. The growth of the colony is evidenced by the appearance of new small patches at new sites on the island. Thus, Choros Island holds ∼95% of the total breeding pairs in Chile.

At Pan de Azúcar Island, the number of breeding pairs seems to have increased from 220 in 1980 to 520 in 2004, but in 2009, 3,317 pairs were reported (Table 3). These estimates were based on a similar methodology; however, there is no explanation for this vast increase. Our estimate of 432 breeding pairs may reflect the actual condition of the colony, as many nests were collapsed, or cobwebs were present, conditions not observed at the colonies of other islands. A more exhaustive monitoring programme would reveal how demographic factors (e.g. chick rates of births and deaths) are mediating the net effects of the environmental factors (e.g. oceanographic conditions and food availability), and ultimately determining the abundance in this colony (Newton Reference Newton1998).

At Pájaros II Island, contrary to expectations, there was a high number of patches (n = 29), but it was possible to determine nest density and burrow occupancy at nine patches. Although Pájaros II is a small, not legally protected island, anthropogenic intervention has likely been attenuated because of the difficult access and distance from the mainland (21.4 km). Because this island was sampled before the reproductive peak, our survey may be an underestimate. Considering that during the reproductive peak the nest occupancy is 60% of active nests (data for Choros Island, see above), we project that ∼340 active nests could be found during the peak of the reproductive period.

Likely, the adequate protection of nesting habitats of the Peruvian Diving-petrel is leading to an increase of their population, particularly on Choros Island that holds the largest number of breeding pairs. However, the population trend should be interpreted carefully, and should not lead us to reconsider the species’ status until reliable time-series from the other main colonies are available.

Overall remarks about the conservation of the Peruvian Diving-petrel in Chile

In this study, we estimated that the Chilean breeding population consisted of ∼12,503 pairs, representing an increase compared to the 1,920 pairs reported in 2002–2003. However, the current Chilean number of breeding pairs is ∼34% of the 36,450 pairs reported for Peru in 2010 (BirdLife International 2019). The smaller size of the current Chilean population probably reflects the precarious conservation state of the species. Several threats (e.g. invasive mammals and unregulated guano extraction; Simeone et al. Reference Simeone, Luna-Jorquera, Bernal, Garthe, Sepúlveda, Villablanca, Ellenberg, Contreras, Muñoz and Ponce2003), and habitat fragmentation due to colony extirpation (e.g. on Pájaros I and Chañaral islands; Luna-Jorquera et al. Reference Luna-Jorquera, Fernández and Rivadeneira2012) are probably preventing the species from recovering to its former abundance. Besides, a genetic study that included five islands (three in Chile and two in Peru) representing their wide-range distribution revealed that the Peruvian Diving-petrel is facing a low migration rate, and significant genetic isolation between colonies, even at very short distances, because of its highly philopatric behaviour (Cristofari et al. Reference Cristofari, Plaza, Fernández, Trucchi, Gouin, Le Bohec, Zavalaga, Alfaro-Shigueto and Luna-Jorquera2019). As a consequence, the overall Peruvian Diving-petrel population is highly fragmented, which implies that the loss of a breeding island will lead to local extinction and the irremediable loss of genetic diversity (Cristofari et al. Reference Cristofari, Plaza, Fernández, Trucchi, Gouin, Le Bohec, Zavalaga, Alfaro-Shigueto and Luna-Jorquera2019). However, few islands in Northern Chile are legally protected, and unprotected islands also hold seabirds that are facing several threats. For instance, invasive rats and guano exploitations are threating Humboldt Penguin Spheniscus humboldti and Peruvian Booby Sula variegata colonies on Pájaros I and Peruvian Booby on Pájaros II islands, respectively (Simeone and Luna-Jorquera Reference Simeone and Luna-Jorquera2012, and Luna-Jorquera et al. Reference Luna-Jorquera, Fernández and Rivadeneira2012). Thus, urgent actions are required to protect existing and to restore former nesting colonies.

Nevertheless, sound conservation plans for the islands containing Peruvian Diving-petrel colonies should include the marine areas around the islands as one conservation unit. For seabirds, the protection of the nesting grounds is as essential as the protection of foraging and resting places at sea. However, there are mining project plans that include the construction of two large ports (http://www.conocedominga.cl, and http://www.capmineria.cl/proyecto-puerto-cruz-grande/) near Choros Island, the most critical breeding location of the species. The existence of these ports could affect the foraging and at-sea resting areas through an increase in maritime traffic, and the lights from ports and human activities could increase the mortality induced by lights (Rodríguez et al. Reference Rodríguez, Holmes, Ryan, Wilson, Faulquier, Murillo, Raine, Penniman, Neves, Rodríguez and Negro2017). By itself, the legal protection of the islands is insufficient to counteract the adverse effects that occur at accelerated rates preventing the recovery of seabird populations. Thus, genuinely effective protection of the islands including both the terrestrial and marine habitats of the Peruvian Diving-petrel can lead, in the long term, to the population recovery of this species that used to be very abundant and is now globally ‘Endangered’.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S095927091900039X

Acknowledgements

We thank CONAF for permission to conduct fieldwork and all volunteers for its participation. Financial support was received from CREOi grants, Proyecto VRIDT 2012-UCN and CONICYT grant No. 21130662 supported the research of CEF.