West Africans and West-Central Africans and their descendants in the Spanish empire were forced to grapple with laws and theological discourses in European empires that sought to legitimize the enslavement of Black people. Enslaved people who disembarked in chains in the port towns of the Atlantic world after surviving the horrors of the Middle Passage often learned about the laws that governed slavery and freedom in European imperial realms and their American colonies through their discussions with other enslaved people in West Africa and West-Central Africa, on slave ships crossing the Middle Passage, and during punishing labor regimes in nascent American slave societies. These ephemeral conversations between enslaved people about the laws of slavery and freedom constituted an exchange of precious knowledge and legal know-how that shaped Black life and thought in the early Atlantic world. In the Spanish empire in particular, enslaved people soon learned that their status was governed by Castilian legal codes of slavery and freedom that outlined limited rights for enslaved people, namely to participate in Christian sacraments of baptism and marriage, and the obligations of a slave-owner to provide sustenance and to refrain from exerting excessive violence and cruelty or abandoning their slaves.Footnote 1 Despite enslaved people’s acute awareness that plotting for their liberty or for elements of freedom through litigation could have violent and fatal consequences for them at the hands of irate enslavers, such conversations sometimes spurred calculated decisions to take the risk and press for their liberty in courts. Historians have documented how enslaved litigants across the Spanish Americas deployed diverse legal strategies to argue for their liberty in royal and ecclesiastical courts.Footnote 2 Some sought to reclaim the liberty that enslavers had illegitimately stolen from them. They drew on Castilian laws of slavery to argue that their enslavement was illegitimate because legal customs prohibited Christians from enslaving other Christians, or that they had been born as free people and therefore could not be enslaved without a just cause that was dictated by the rule of law in their regions of origin, or that they had already been liberated from slavery under Castilian laws and could not be reenslaved.Footnote 3

Ephemeral conversations among enslaved people about the laws of freedom and slavery shaped Black legal consciousness, and also propelled some people to petition royal courts for their liberty on the basis of their illegitimate enslavement. This chapter charts a history of conversations among enslaved Black people about Castilian laws of slavery and freedom, analyzing the discourses of illegitimate enslavement that were deployed by enslaved litigants and their witnesses across three freedom suits in Castilian royal courts in 1536, 1547, and 1614 (Figure 5.1).Footnote 4 These litigants argued for their freedom on the basis that they had been illegitimately enslaved and that their freedom had been stolen from them. Pedro de Carmona, for example, protested in his petition in 1547 about the “great injury and disturbances (agravios y turbación) that have been done to my liberty.”Footnote 5 These rare instances when enslaved people managed to plead their cases in royal courts for freedom from illegitimate enslavement reveal hushed whispers among enslaved and free people about the laws of slavery and freedom and the illegitimacy of certain types of enslavement. Each of the litigators participated in conversations with others about their illegitimate enslavement and shared strategies and experiences with other enslaved, liberated, and freeborn Black people whom they encountered in different sites across the Atlantic world. Discussions about the illegitimacy of certain types of enslavements moved from place to place through diverse exchanges of information, fractured memories, and knowledge, often being spearheaded by enslaved people seeking to reclaim their stolen freedom. Black litigants often accrued their knowledge through discussions with other enslaved and free Black people during desperate attempts to reclaim the freedom that had been stolen from them. This is most evident in my assessment of the role of the famed Dominican friar Bartolomé de Las Casas in Pedro de Carmona’s litigation for freedom in the Council of Indies in 1547. While Carmona enlisted the help of the friar in his desperate pursuit of his looted liberty, the chapter concludes that Casas’ shaping of Carmona’s legal knowledge was likely minimal, as Carmona had already spent years pursuing his case for freedom from illegitimate enslavement in local royal courts before meeting the friar. Instead, perhaps Carmona influenced Casas’ shifting views; the friar began to regard the enslavement of Black Africans as illegitimate soon after meeting Carmona, an idea that he elaborated in Brevísima relación de la destrucción de África in the mid sixteenth century.Footnote 6

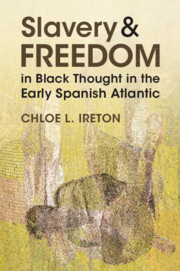

Figure 5.1 Map of the Southern Atlantic, with lines showing the enslavement and forcible displacements across the Atlantic of Domingo de Gelofe, Pedro de Carmona, and Francisco Martín.

Domingo gelofe

In 1536, Domingo Gelofe submitted a petition for his liberty to a fiscal (official) of the Council of the Indies who was stationed in Sevilla.Footnote 7 In his petition, Domingo pleaded that judges should liberate him from slavery and declare him a free man because he had been born as a free person in West Africa, and had been illegitimately enslaved by a Portuguese ship captain, being forcibly displaced to the Americas and then to Castilla.Footnote 8 According to Domingo’s petition, he was born a free Christian and his father was an “honorable man” (hombre principal) in West Africa, likely in the Jolof empire, where he had learned how to speak Portuguese.Footnote 9 Domingo positioned his initial departure from his native land as a voluntary act,Footnote 10 relaying that he had developed relationships through trade and friendship with Portuguese traders in Gelofe and had decided to leave with a Portuguese trader in order to learn more about Christianity and to become fluent in the language of the Christians. Domingo and his Portuguese party reportedly departed Gelofe and arrived at the island of Tenerife in approximately 1529/30.

Domingo explained that a captain in a Spanish armada had illegitimately enslaved him in Tenerife. He soon found himself aboard a ship in the fleet of an early sixteenth-century conquistador named Diego de Ordás, who was crossing the Atlantic in search of El Dorado.Footnote 11 Ordás had left the town of San Lucar de Barrameda, located at the mouth of the Guadalquivir River in southern Castilla, on October 20, 1530 with 500 men and thirty horses, and at least one Indigenous American interpreter.Footnote 12 The fleets docked in Tenerife, where Ordás possessed a royal license to source an extra 100 men and horses for his armada, and where the fleet would also collect provisions for the journey.Footnote 13 Domingo’s forced Atlantic journey from Tenerife to the Americas lasted two years, with the armada reaching the Gulf of Paría (present-day coastal Venezuela) and returning to Castilla in 1532; Ordás perished at sea.Footnote 14 During the two-year Atlantic odyssey, ownership of Domingo transferred from the captain who had reportedly snatched him in Tenerife to Diego de Ordás, suggesting that perhaps Domingo became the personal slave to the conquistador who was at the helm of the armada.Footnote 15 After the surviving members of the armada returned to Castilla in 1532, judges at the House of Trade in Sevilla considered Domingo as part of the late Ordás’ estate when adjudicating between competing heirs in the probate case.Footnote 16

Domingo’s petition to the Castilian monarch for his liberty reflects a history of ideas and legal customs about slavery and freedom in his native tierra Gelofe. Domingo engaged in a conversation, through his 1536 petition, with Castilian rulers who were well acquainted with his place of origin. Since at least the early fifteenth century, Portuguese and Castilian monarchs had been aware of the kingdoms and polities that constituted Western Africa, in particular of the Jolof “expansionist kingdoms” and the subsequent political fragmentation of the Jolof empire in the fifteenth century.Footnote 17 These political pressures had led to Jolofs being the majority of enslaved Black people who were exported to the Atlantic world in the first two decades of the sixteenth century.Footnote 18 An uprising led by enslaved Jolof people in 1522 in Isla Hispaniola led to a decade-long attempt by the Spanish crown to prohibit slave traders from exporting enslaved Gelofes to the Spanish Indies.Footnote 19

Domingo’s argument that the illegitimacy of his enslavement rested on his voluntary departure from tierra Gelofe may relate to ideas about just war in the Jolof empire. The custom in Jolof kingdoms (and Senegambia more broadly) was that war between major political foes was a legitimate reason for enslavement, but intralineage and village raids were not; these reasons were common in Upper Guinea, for example.Footnote 20 Consequently, as Toby Green has argued, most of those taken from Jolof were “war captives procured through attacks from Cajor and the Sereer.”Footnote 21 Domingo’s legal strategy of identifying as a Christian in order to argue for the illegitimacy of his enslavement may also have been the result of his exposure to ongoing inter-African creolization processes in the Jolof kingdoms or syncretic New Christian–Sephardic–Senegambian communities that emerged in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries on the Petite Côte in Senegambia, following the settlement of exiled New Christian communities from Iberia and Amsterdam.Footnote 22 Descendants of New Christian–Sephardic–Senegambian communities formed part of extensive trading networks and possessed a deep knowledge of Iberian laws and Catholicism.

Displaced into early sixteenth-century Sevilla, Domingo navigated various avenues of royal justice to pursue his case for freedom, culminating in his petition to the Council of the Indies in 1536. This appeal to the crown also suggests an engagement with broader discussions about just war and the illegitimacy of enslaving non-Christians that were ongoing in Sevilla, the city where he languished for four years as a slave owned by Ordás heirs prior to submitting his petition for freedom. As Nancy Van Deusen has noted, intense debates about the legitimacy of the enslavement of Indigenous Americans took place in early sixteenth-century Sevilla, following the enslavement and forcible displacement of more than 650,000 Indigenous Americans across the Indies. Over 2,000 Indigenous Americans were displaced to Castilla, mostly to Sevilla, as slaves.Footnote 23 During this period, Dominican friar Bartolomé de Las Casas was involved in a protracted effort to outlaw the enslavement of Indigenous Americans in the New World on the basis that such enslavements occurred as a result of just wars.Footnote 24 The debates resulted in what Van Deusen describes as the passing and rescinding of “contradictory and piecemeal” legislation in Castilla that “excluded slavery only in some areas, temporarily prohibited slavery (1530), and later reestablished slavery under conditions of just war and ransom (1534, 1550), and granted exceptions to individual merchants and families making transatlantic journeys to Castilla by ignoring laws that prohibited the transportation of slaves away from their places of origin.”Footnote 25 Finally, the crown introduced the New Laws in 1542, prohibiting Indigenous slavery. As Van Deusen has explored, the New Laws were followed by two royal inspections in Sevilla in 1543 and 1549, to investigate whether any Indigenous Americans continued to be illegitimately enslaved in that city and its environs; this resulted in the liberation from slavery of 100 Indigenous people.

A thriving discourse therefore existed in Castilla, and particularly in Sevilla, in the 1530s regarding the legitimacy of enslaving Indigenous Americans. This discourse was not limited to theological and royal spheres, as neighbors and friends on street corners in Sevilla and neighboring towns also discussed and debated the laws with regard to just war and Indigenous slavery. As Van Deusen shows, hundreds of enslaved Indigenous Americans who litigated to secure their freedom between 1530 and 1585 shaped discourses of slavery in Sevilla by seeking witness testimonies from their friends and neighbors.Footnote 26 City dwellers also heard about broader discussions concerning the illegitimate enslavement of Indigenous Americans through town criers at Gradas and other prominent sites in Sevilla, who sung royal decrees that announced the prohibition of Indigenous slavery.Footnote 27

Domingo’s petition is indicative of how debates about illegitimate slavery in Sevilla also extended to the enslavement of Black Africans. Such a development is not surprising given that free Black individuals from Sevilla and the nearby town of Carmona often served as witnesses in cases involving Indigenous litigators’ American naturaleza.Footnote 28 In so doing, they played a role in shaping discourses of just war and the illegitimacy of Indigenous Americans’ enslavement in the city’s courts. One might surmise that Black dwellers of Sevilla who provided witness testimonies in this way might also have questioned the legitimacy of their own enslavement. Familial and commercial ties between Black witnesses living in Carmona and Sevilla, as documented by Van Deusen, also highlight that ideas and knowledge about Indigenous people’s freedom trials were exchanged between Black residents in neighboring towns in southern Castilla. However, ties between free and enslaved Black people living in Sevilla and Carmona were only a fraction of the webs that connected Black communities in Sevilla and towns dotted across southern Castilla and the Spanish Atlantic more broadly. Early sixteenth-century Sevilla had a significant Black population of free and enslaved people who had ties with the broader Atlantic world.Footnote 29 In the city, Domingo would have encountered Black individuals from the Jolof empire, in addition to enslaved Black people from Cabo Verde, Upper Guinea, as well as those born in Spain, Portugal, and the Americas.

Domingo’s argument for freedom differed in important ways from the arguments put forward by Indigenous litigants in the same period. Indigenous people argued that their illegitimate enslavement stemmed from the fact that they were not Christians at the time of their capture.Footnote 30 This was the opposite to enslaved Black litigants, such as Domingo, who argued that he was a freeborn Christian and that his Christianity predated contact with the Portuguese. Domingo’s argument for the illegitimacy of his enslavement rested on two key ideas: (1) the illegitimacy of enslaving someone who was born free and who had not been subject to enslavement as a result of a just war, and (2) the Castilian rule of law, derived from the Siete Partidas, that Christians could not legitimately enslave other Christians, regardless of their skin color. In other words, Domingo did not propose that the enslavement of Black people per se was illegitimate. Instead, he implicitly argued that it was the enslavement of freeborn Black Christians that was illegitimate. Domingo played on four issues in his petition: (1) his father being a man of honor; (2) his being a freeborn Christian prior to meeting the Portuguese; (3) his desire to voluntarily travel with Portuguese traders in order to learn more about the Christian faith and Christian languages; and (4) the conquistador, Diego Ordás, recognizing that Domingo was a free man who had been illegitimately enslaved, and subsequently freeing him. Domingo’s legal argument of illegitimate enslavement thus relied on the notion that he was already in possession of his liberty and that he was a Christian in Gelofe, which rendered any enslavement illegitimate.

Strikingly, the monarch’s response to Domingo’s petition highlights an element of doubt in the official mind of the Spanish empire (in this case, the Council of the Indies) regarding the legitimacy of enslaving free Black Christians. In March 1537, four months after launching his petition, Domingo obtained a royal decree that guaranteed his status as a free man.Footnote 31 The royal decree stated unequivocally that Domingo, “of Black color,” was – and always had been – free and should be treated as a free man in all the kingdoms of Castilla, the Indies, and Tierra Firme. The decree reasoned that not only had the conquistador Diego de Ordás freed Domingo in his testament, but also that Domingo’s freedom was guaranteed because he “came with them [the Portuguese] to be a Christian, as he is,” suggesting that the crown agreed with Domingo as to the illegitimacy of his entire ordeal in captivity because of his status as a freeborn Christian in tierra Gelofe. The existence of the royal decree suggests that the crown’s view on the legitimacy of the enslavement of Black people in West Africa – especially Christians – was sometimes piecemeal and reactive to individual petitions.Footnote 32 Domingo’s petition of 1536, and the royal response in 1537, demonstrate the existence of a discussion between rulers and enslaved subjects about the conditions that rendered slavery legitimate in the early decades of the sixteenth century, especially in relation to free Black Christians.

The available evidence suggests that the royal decree stipulating Domingo’s freedom in 1537 resulted in his obtaining the status of a free man in the Castilian realms, as he was recorded as a passenger on a ship in Sevilla the following year, poised to travel to Peru using the 1537 royal decree as evidence of his freedom.Footnote 33 House of Trade officials recorded Domingo as a free Black man and noted the 1537 royal decree that established his freedom.Footnote 34 Domingo’s travel record specified that he left Sevilla for Peru employed as a wage-earning servant (criado); he may well have taken this job for a specified time period in order to pay for his Atlantic crossing, or he may have found himself in a state of forced servitude even though he was legally free.Footnote 35 Over the course of his life, Domingo likely discussed his litigation for freedom with others he encountered in Castilla, on the ship that sailed across the Atlantic, and in Peru.

Judges at the Council of the Indies continued to receive other information about the illegitimate enslavement of Black people in the crown’s realms during this period, and issued royal decrees that attempted to ensure that structures of royal justice were available to those who claimed that they had been illegitimately enslaved. For example, in 1537, the Council of the Indies adjudicated on a case of appeal pertaining to the freedom from illegitimate enslavement of a Black horro named Rodrigo López who had been snatched from Cabo Verde and displaced to the Caribbean as a slave.Footnote 36 After many frustrated attempts to access royal justice, López managed to prove his freedom in the Real Audiencia of Santo Domingo after his liberated Black sister heard news of his whereabouts and sent copies of his freedom papers from Cabo Verde to Santo Domingo via a relay of merchants and messengers.Footnote 37 Such complaints of illegitimate enslavement continued to reach judges at the Council of the Indies. In 1540, the monarch issued a royal decree noting that the royal court had received complaints from enslaved Black people in the Spanish Caribbean, who described how slave owners in the Tierra Firme region routinely enslaved many free Black Africans and prevented them from accessing the courts to prove their freedom.Footnote 38 The decree ordered officials in Tierra Firme to ensure that any Black people who sought to reclaim their freedom after being illegitimately enslaved could access local courts to prove their cases for liberty.

Pedro De Carmona

In August 1547, an enslaved Black man named Pedro de Carmona appeared in person at the Council of the Indies and presented a petition that described his history of violent enslavement, dispossession, and displacement across various sites in the Atlantic world.Footnote 39 In his 1547 petition, Carmona described that he was a Black man born in West Africa, who had been “stolen and brought from my land [West Africa] from the breasts of my mother,” and forcibly displaced to Castilla as a child.Footnote 40 By the age of thirteen or fourteen, Pedro de Carmona’s owner, Juan de Almodóvar, had taken him from Castilla to Puerto Rico.Footnote 41 Carmona relayed that he enjoyed a close relationship with his owner, describing how Almodóvar had entrusted him to look after his mines on a nearby island in the Spanish Caribbean. He also reported that Almodóvar had permitted him to save some money to purchase an enslaved Black woman named Isabel Hernández, whom Carmona had subsequently married in 1533; the pair had lived as husband and wife while enslaved to Almodóvar.Footnote 42 Carmona reported that his owner had promised to liberate himself and his wife upon his death in gratitude for his service, and had written a liberation clause in his testament. He explained that “to discharge his conscience and for the good services that I gave him and the profit that my labor brought to his estate, in the testament that he made before he died, he left me in absolute freedom and without imposing any condition or limitation on my freedom.”Footnote 43

Carmona’s 1547 petition for freedom owing to his illegitimate enslavement rested on the fact that he had been illegitimately sold into slavery after his liberation on Almodóvar’s death. Despite the liberation clause, Carmona reported that he did not receive his liberty after his owner’s death.Footnote 44 He described how he had heard news of Almodóvar’s death while overseeing his owner’s mines and estate on a nearby island. Carmona reported that after this he had returned to San Juan in Puerto Rico to retrieve Almodóvar’s testament, with the intention of obtaining his freedom.Footnote 45 In San Juan, the notary refused to show Carmona the testament, thereby denying him the opportunity to claim his liberty. Instead, the notary secretly sold Carmona’s wife, Isabel Hernández, to religious clerics, and then sold Carmona to a merchant named Hernando Alegre. Carmona described how he had fled from the city of San Juan to his late owner’s estate after learning that his wife had been sold into slavery and that his new owner had sought to imprison him in chains. Having approached the archbishop of Puerto Rico to seek justice for his case within a few days of fleeing, Carmona reported that the archbishop had been unwilling to intervene. Thereafter, he learned that his wife had been displaced to the city of Santo Domingo in Isla Hispaniola. He subsequently obtained permission from his new owner, Alegre, to travel there to search for her. Alegre, however, had surreptitiously instructed his son, Francisco, who was living in Santo Domingo, to sell Carmona – who detailed how Alegre junior sold him secretly when he arrived in Santo Domingo to a merchant named Melchor de Torres, who resided there.

Although Carmona had been reenslaved twice since his owner’s death, the city of Santo Domingo proved to be a place where he had a greater chance of accessing the ear of the king through royal courts than he had in Puerto Rico: Santo Domingo was the seat of the Real Audiencia for the region. While enslaved there, Carmona pursued a litigation-for-freedom suit in the Real Audiencia.Footnote 46 However, the centrality of paperwork for evidentiary thresholds in royal courts of justice thwarted his initial efforts. Carmona did not have a copy of Almodóvar’s testament, as the notary in Puerto Rico had refused to share a copy with him. As he lacked any proof of his liberation from slavery, the judges in the Real Audiencia declared that he had not proved that he was free and pronounced in favor of his owner, Melchor de Torres.Footnote 47 In his later petition to the Council of the Indies, Carmona described how the judicial process in Santo Domingo’s Real Audiencia was beset with corruption, the courts acting in favor of the powerful mercantile interests of his new owner rather than himself. He complained that those who had promised to defend his interests had done so insincerely, likely referring to his court-appointed procurator.Footnote 48

Despite the ruling, Carmona managed to launch an appeal at the Real Audiencia. The judges ruled in his favor, granting the litigant a two-year period to travel to Puerto Rico, gather the necessary paperwork, namely his previous owner’s testament, then return to the court and prove his freedom.Footnote 49 As far as Carmona was concerned, this judgment granted him temporary reprieve from his illegitimate enslavement, and the freedom and protection to travel to Puerto Rico to seek proof of his liberty before returning to the court. Melchor de Torres took a different view, and sold Carmona within four or five days of the judgment to an unsuspecting new owner. According to Carmona, Melchor de Torres imprisoned both him and his wife in chains and forced them to board a ship that departed from Santo Domingo to Honduras.Footnote 50 Carmona’s efforts to seek royal justice through the local royal courts and religious authorities in Puerto Rico and Santo Domingo were therefore frustrated by corruption in the local courts, uninterested judges, and unscrupulous and powerful slave-owners who disregarded the rule of law and rulings issued by the Real Audiencia.

The series of events that led Carmona to cross the Atlantic to the Council of the Indies in Castilla highlights his indefatigable quest for royal justice, and how he shared and exchanged information about his legal strategies to recover his stolen freedom across various sites in the Spanish Caribbean. Although Melchor de Torres displaced Carmona from Santo Domingo, the city where the royal court had finally ruled in his favor, Carmona did not abandon his quest for justice. Reportedly, he voiced concerns about his illegitimate enslavement with those he met along the way, and also after arriving in San Juan de Puerto de Caballos (present-day Puerto Cortés), where he and his wife were resold by one of Torres’ agents. In San Juan de Puerto de Caballos, Carmona may have been advised by passers-by to travel to the city of Gracias a Dios, where the Real Audiencia for Guatemala had recently been established, in 1544, or he may have been sent by Torres to be sold in that city, which was 225 km from the port.Footnote 51 Carmona later reported that the power and influence of his previous owner, Torres, had thwarted his attempt to have his case for justice heard in that court.Footnote 52

In Gracias a Dios, Carmona continued to discuss his litigation to reclaim his liberty. These conversations resulted in his receiving advice to seek the counsel of some priests who had arrived in Cabo de Gracias a Dios and were also petitioning the Real Audiencia.Footnote 53 This was when Carmona first encountered Bartolomé de Las Casas, the famed bishop of Chiapas and Dominican friar who had been engaged in a protracted political effort to outlaw the enslavement of Indigenous Americans and was stationed at the Real Audiencia between July 21 and November 10, 1545, to submit petitions to ensure the proper implementation of the New Laws in the region.Footnote 54 Among Casas’ entourage was a Black man named Juanillo, who may have been the person who Carmona first spoke with about his case.Footnote 55 After Carmona had established contact with the priests, Casas took an interest in his plight and convinced him to cross the Atlantic to Castilla to present his case for freedom from illegitimate enslavement to the highest royal court for issues pertaining to the Spanish Americas, the Council of the Indies.Footnote 56

This transatlantic history of a Black man’s quest for justice and freedom from illegitimate enslavement in the mid sixteenth century reflects the importance of paying attention to how ideas moved across different sites. Carmona spoke about his litigation to recover his stolen freedom after his illegitimate enslavement with people he encountered in the four sites of the Caribbean to which he was displaced (Puerto Rico, Santo Domingo, San Juan de Puerto de Caballos, and Gracias a Dios), while also instigating litigation and appeal suits in the highest royal court in the Spanish Caribbean, namely the Real Audiencia in Santo Domingo. His petition for freedom there forced judges, procurators, and owners to deliberate on his case; but he also discussed his case informally with passersby, other enslaved people, and free people as he desperately sought anyone who might be able to help him to find justice. For example, when Carmona and his wife arrived in San Juan de Puerto de Caballos, in chains on board a ship, he spoke with enough people about the injuries to his liberty and his illegitimate enslavement to eventually receive the advice to go to the Real Audiencia of Guatemala in Gracias a Dios and to seek the counsel of some priests stationed there who might help him. Through those conversations, Carmona spearheaded the exchange of knowledge and ideas about litigation for freedom in royal courts, legal strategies, and questions about the Castilian laws of legitimate enslavement and how to reclaim stolen freedom, while also informing other enslaved and free Black people about his fight for freedom and the arguments that he deployed in the courts.

Although it might be tempting to attribute Carmona’s crossing of the Atlantic to the Council of the Indies in 1547 to Bartolomé de Las Casas’ support and patronage, this would be paying a disservice to Carmona and his bid for freedom using the royal courts prior to encountering the friar. Carmona was a knowledgeable imperial subject who understood Castilian laws of slavery and freedom, and how to present his arguments forcefully and convincingly. Before meeting Casas, Carmona had already appealed to ecclesiastical justices in Puerto Rico, then fled, taken his case to be heard at the Real Audiencia in Santo Domingo, and mounted his own appeal, which he partially won. And when his owner did not respect the judgment, Carmona once again sought the ear of another court of justice, the Real Audiencia in Guatemala, and only then finding his way into the path of Casas. When Casas suggested that he submit a petition to the Council of the Indies regarding the theft of his liberty, it is likely that Carmona was already aware that this court existed.Footnote 57 The historian Pérez Fernández has suggested that Casas provided Carmona with a vale (certificate) to travel from Gracias a Dios to Havana, where the pair met again, traveling together to Castilla via Lisbon.Footnote 58 While this is plausible, Carmona’s multiple litigations and conversations across different sites also reveal his acute awareness of the law, structures of justice, and how to move across vast spaces in the Spanish Atlantic. Lacking a freedom certificate, however, would have made any Atlantic journey more difficult and dangerous without the help of Casas.

Through a series of well-presented written petitions dated between August and September 1547, most likely guided by Casas, Carmona described how he had crossed the Atlantic in pursuit of his liberty: “Pedro de Carmona, of moreno color, I say that having come from the Indies to your Royal Council of the Indies to ask for justice for the great injury and disturbances (agravios y turbación) that have been done to my liberty.”Footnote 59 He described this transatlantic journey to pursue his liberty as his final chance for justice after his owner had imprisoned him and his wife in chains on a ship to be sold in Honduras. Carmona described the injustice that he and his wife faced with the following lines:

as disfavored and scorned and despised people, we could not find justice for these mistreatments and injustices. And seeing that I had no other remedy but to request that your majesty order that justice be served. Of which, I humbly supplicate that your majesty order in such a way that I obtain my rightful/owed liberty and that of my wife too.Footnote 60

Carmona was well aware of the Castilian laws of slavery that prevented the reenslavement of liberated people. He presented himself as a Christian who deserved access to justice, while describing how his former owners, the notary in Puerto Rico, and royal judges in Santo Domingo had behaved in an un-Christian manner as they had looted his liberty.Footnote 61 This notion of the illegitimacy of a third party disturbing or looting someone’s liberty in Castilian law is summed up by a procurator in another petition for freedom half a century later, this time in royal jurisdiction of the property court (camara y fisco real) within the Holy Office of the Inquisition of Sevilla in 1594. The litigant, a Black man named Juan Rodríguez, who resided in Cádiz and found himself listed as the property within his previous owner’s estate, argued that Castilian laws spelled that his enslavement was illegitimate because he was a Catholic owned by an enslaver who the Inquisition had condemned as a “Judaisizer.” In doing so, he drew on the Castilian laws of slavery as outlined in the Siete Partidas that specified that people of Jewish and Muslim faith could not own Christian slaves.Footnote 62 Juan Rodríguez’s procurator explained that once someone obtained liberty – as Juan Rodríguez had – such a person could not be “returned to captivity,” arguing that “Juan Rodrigues obtained his liberty … and having obtained liberty one time, he who obtained liberty cannot be returned to slavery except if there is a new cause and there has not been a new cause.”Footnote 63 Here, the procurator was referring to another stipulation within the Las Siete Partidas that detailed how a liberated person could not be returned to slavery unless a new legitimate cause for enslavement emerged, such as becoming a captive in a just war. In his petition half a century earlier, Carmona was drawing on similar knowledge of these legal codes that prohibited the reenslavement of someone who had been liberated from slavery without a just cause. In particular, he also positioned his latest owner, Melchor de Torres, as a corrupt figure who had disregarded the rule of law by selling him after the Real Audiencia in Santo Domingo had issued a judgment that permitted Carmona to travel to Puerto Rico to search for his freedom papers.

Casas accompanied Carmona to the Council of the Indies, which prior to 1561 was an itinerant court and was at this time located in the town of Aranda. He offered Carmona unwavering support and patronage throughout his petition to the Council of the Indies in 1547. In the first instance, various witnesses in Casas’ retinue testified on Carmona’s behalf, explaining that he had met Casas in Cabo de Gracias a Dios near Honduras and describing how he had become Casas’ criado after that interaction.Footnote 64 In the second instance, Casas offered to pay a bond to the court of the Council of the Indies as an assurance of Carmona’s integrity.Footnote 65 This is because de Torres had alerted officials across the Atlantic that Carmona was a fugitive slave after he left Honduras, and requested that they detain him. As a result, upon arriving in Aranda, Carmona was arrested and imprisoned. During the judges’ deliberations, Casas agreed to pay a bond to the court – staking his worldly possessions – for Carmona to be freed from jail.Footnote 66 This document bears Casas’ signature and those of others in his retinue who witnessed the agreement.

It is possible that Carmona’s story of illegitimate enslavement contributed to Casas’ shift in perspective about the illegitimacy of the enslavement of Black Africans, as Casas came to view African slavery as similarly illegitimate to indigenous slavery by the mid sixteenth century.Footnote 67 In 1552, Casas wrote a scathing attack of the enslavement of Africans in Brevisima Relacion de la Destruccion de Africa, describing how “of more than 100,000 [Black slaves], it is not believed that more than ten had legitimately been enslaved.”Footnote 68 Casas argued that only three acceptable causes existed for a just war against infidels and their enslavement, and that no such conditions existed for the legitimate enslavement of Black Africans anywhere in Atlantic Africa between the Canary Islands and the Cape of Good Hope.Footnote 69 The first cause related to contexts where infidels waged war against Christians and attempted to destroy Christianity. Only the Turks of Barbary and the Orient counted in this claim, he argued, because they waged war against Christians every day and had a long history of showing intent to harm them. There was thus no doubt that the Christians were engaged in a just war against Turks. In fact, to Casas, Christians should not describe such a situation as a just war, but rather as legitimate and natural defense. The second cause related to infidels persecuting or maliciously impeding the Christian faith, for example by killing its devotees and preachers without any legitimate cause, or by forcing Christians to renege on their faith. Such acts hindered the practice of the Christian faith and were grounds for just war and enslavement. The third and final reason that would allow for a just war in Africa applied when infidels attempted to destroy or conquer Christian kingdoms. Casas added that under no circumstances could an individual’s infidel status alone serve as a just cause for his or her enslavement. In short, by the mid sixteenth century, Casas had rejected the enslavement of Black Africans as illegitimate; the practice was as abhorrent and illegal as the enslavement of Indigenous people in the Americas. He posited that King João III of Portugal (King of Portugal and the Algarves 1521–1557) had realized the legal error of trading slaves with Muslims and had prohibited the practice, but noted that the monarch had failed to realize the widespread sin of stealing Black individuals from their lands. Casas wrote, “but he [João III] did not prevent the rescate [purchase of enslaved people] and the one thousand mortal sins that are committed in it, swelling the world of Black slaves, at least in Spain, and even making our Indies overflow with them.”Footnote 70 While such critiques did not spark a ferocious debate, such as those about the legitimacy of the enslavement of Indigenous Americans that had taken place mere decades earlier in Castilla and had led to legislation outlawing their enslavement, Casas’ refutation of the legality of the enslavement of Black Africans demonstrates that these debates were taking place in the sixteenth century.Footnote 71

Judges at the Council of the Indies ruled in 1547 that Carmona should be given a two-year license to travel to Puerto Rico in order to retrieve the documentation that would prove his freedom and then to pursue his case for freedom from illegitimate enslavement in the courts in the Spanish Caribbean.Footnote 72 They then issued three royal decrees in the year following their initial pronouncement, these serving as temporary freedom papers for Carmona.Footnote 73 The decrees sought to compel royal officials to ensure Carmona’s safe passage to Puerto Rico and access to royal justice for his case. In the first instance, Carmona’s initial departure from Castilla was delayed because judges at Sevilla’s House of Trade refused to grant him an embarkation license. On April 17, 1548, one year after the courts’ initial pronouncements, the crown sent a royal decree to the House of Trade in Sevilla instructing judges to allow Carmona to travel to Puerto Rico, noting that the Council of the Indies had received information that judges had refused to grant him a license.Footnote 74 Another royal decree, dated February 21, 1548, instructed judges at the House of Trade and other ports to allow Carmona to travel freely to Puerto Rico and to present his case for freedom at the Real Audiencia in Santo Domingo.Footnote 75 The decree instructed royal officials not to harm or imprison him because he had paid a bond. This had been insured by Casas, who had staked his worldly possessions. A third royal decree compelled the public notary who had certified Carmona’s owner’s testament in Puerto Rico to make the document available to Carmona for his case.Footnote 76 The existence of these decrees suggest that Casas followed the case after the initial judgment and continued to lobby for Carmona over the following months. Perhaps he foresaw possible problems, such as Carmona’s ability to obtain an embarkation license at the House of the Trade in Sevilla, in compelling an unwilling notary in Puerto Rico to produce the testament, or that one of the slave-owners who claimed Carmona as their slave might attempt to recapture him. These royal decrees would have provided Carmona with some added security and protection during his quest for freedom.

These royal decrees reveal some of the conversations about slavery and freedom that Carmona participated in across the Atlantic world while he pursued his case for freedom, most notably during his residence in the city of Sevilla in 1547/8 while he awaited royal permission to cross the Atlantic to Puerto Rico. It is likely that he continued to discuss his ongoing legal fight for freedom with free and enslaved Black people in the city of Sevilla and on the ship destined to the Americas, if he did eventually embark on the voyage. Unfortunately, I have not been able to locate any further records to determine whether Pedro de Carmona crossed the ocean to Puerto Rico and whether he was able to retrieve his owner’s testament and prove his freedom in the courts in the Spanish Caribbean. Nor do I know whether he was ever reunited with his beloved wife, Isabel Hernández, whom he had last seen in chains in Honduras about to be sold and reenslaved.

Francisco Martín

Early seventeenth-century Cartagena de Indias became the highest-volume slave-trading port of the Hispanic Atlantic with at least 487 slave ships disembarking over 78,453 enslaved Africans between 1573 and 1640.Footnote 77 According to a procurator in early seventeenth-century Cartagena, it was widespread knowledge in the port town of Cartagena de Indias that slave traders often brought enslaved Africans to the port in “bad faith” as “[slave traders] trick free black people and take them from their lands and bring them here to be sold as slaves.”Footnote 78 So endemic was the problem of illegitimate enslavement in West Africa that illegitimately enslaved free Black Africans who had endured forced displacements on slave ships through the Middle Passage would arrive in Cartagena proclaiming their liberty “with loud voices (a voces)” when they were coming ashore. These proclamations are those made by a procurator named Francisco Gómez who defended an enslaved litigant seeking his freedom in the Cartagena court in 1614. Gómez explained how such Africans “arrive here shouting that they had been born free and that they are children of free parents and had come to a state of servitude.” That act of shouting and using their voices to proclaim their liberty, Gómez clarified, allowed Cartageneros to “know they are free” and that they had been illegitimately enslaved, for such Africans “know how to proclaim their liberty.” Noting legal precedent, Gómez referred to former legal cases in Cartagena courts in which illegitimately enslaved Black Africans had pursued justice, of which he noted, “there are a great number in which they have been liberated as free.” Gómez’s argument is revealing, suggesting that in Cartagena the illegitimate enslavement of free Africans might have been notorious, that some Africans may have disembarked in Cartagena loudly proclaiming their freedom in Spanish or Portuguese, and, more importantly, that similar litigations for illegitimate slavery had been heard and won in the past.

The Jesuit priest, Alonso de Sandoval, who was based in Cartagena and dedicated his missionary life to tending to enslaved Black Africans’ souls, also described the existence of these lawsuits. In his treatise titled Naturaleza, policia sagrada i profana, costumbres i ritos, disciplina i catechismo evangelico de todos Etiopes (The nature, sacred and profane government, customs and rites, and discipline and evangelical catechism of all Ethiopians), dated 1627, Sandoval dedicated an entire chapter to the question of the legitimacy of the enslavement of Black Africans and pointed to such litigations in Cartagena.Footnote 79 As he explained, “the debate among scholars on how to justify the arduous and difficult business of slavery has perplexed me for a long time.”Footnote 80 Sandoval described how different slave traders had approached him in Cartagena to seek his counsel on whether their slave trading was legitimate and moral, as they doubted whether the Africans that they had brought to the Indies had been legitimately enslaved. He recounted how “a captain who owned slave ships that made many voyages to those places [São Tomé],” and who had enriched himself, found that “his conscience was burdened with concern over how these slaves had fallen into his hands.” The captain reported to Sandoval his discomfort with how “one of their kings imprisoned anyone who angered the king in order to sell them as slaves to the Spaniards.” Another slave-ship captain confided in Sandoval:

Father, I go to buy Black people (as an example) to Angola, and along the way I endure a great amount of effort, costs, and many dangers. In the end, I leave with my cargo, some of the Black people legitimately enslaved and others not. I ask, do I satisfy the justification of this captivity with the efforts, costs, and dangers that I had to endure in going and coming until selling them in Christian lands, where they might continue to live as gentiles?

Sandoval’s concern for the legitimacy of the enslavement of Black Africans led him to conduct interviews with slave traders, captains, free and enslaved Africans, priests, and officials in Cartagena de Indias, while he also engaged in correspondence with Jesuits in Luanda and São Tomé to inquire about their views on the legitimacy of enslaving Africans. Importantly, he also reviewed legal cases from Cartagena courts in which Black people argued that they had been illegitimately enslaved in West Africa. Sandoval summarized the transcript of a legal case that he had consulted in which a Black man from Guinea was trying to prove that he was legally free in Cartagena courts. The enslaved man reported that he had been illegitimately enslaved and forcibly displaced to Cartagena, being considered and treated as a free man in Guinea, but Sandoval reported that the court ruled that “although it could be proved that he was legally a slave, he could not prove his freedom.”Footnote 81

Discussions about the legitimacy of enslavement in Cartagena among enslaved people are also evident in the litigation for freedom suit that was brought by a young enslaved Black man named Francisco Martín who hailed from the port of Cacheu in Upper Guinea. Martín disembarked from a slave ship in Cartagena on June 5, 1614.Footnote 82 According to the ship’s register, the captain named Antonio Rodríguez de Acosta had set sail with 359 enslaved people onboard, but only were 287 disembarked in Cartagena, meaning that 72 people likely perished during this treacherous journey through the Middle Passage.Footnote 83 Upon arrival, Martín litigated for his freedom on the basis that his enslavement had been illegitimate.Footnote 84 In Cartagena he was able to locate enslaved and free Black people who knew him from the port town of Cacheu and who agreed to testify, and their testimonies reveal extended discussions among enslaved people about the meanings and legitimacy of slavery across legal jurisdictions.

Martín’s first encounter in Cartagena de Indias – or, more likely, in a bay where the ship would have docked prior to arriving at the port – may have been with Alonso de Sandoval and his coterie of free and enslaved African interpreters. This is because Martín arrived into a spiritual world that was concerned with the ubiquitous practice by religious clerics in West and West-Central Africa and on slave ships of administering the sacrament of baptism without ensuring that those receiving the baptism understood or agreed to it, thereby rendering the sacrament null or false.Footnote 85 Sandoval, and later his disciple Pedro de Claver (1580–1654), who joined the Cartagena Jesuits in 1615, dedicated their missionary energies to tending to enslaved Africans’ souls.Footnote 86 Sandoval, in particular, became concerned, through his contact with enslaved Africans, that many baptisms that took place in “those lands [Africa], and ships” were “commonly null and at least doubtful.”Footnote 87 This concern strengthened his sense of the importance played by priests in the principal ports of disembarkation of African slaves – “Lisbon, Sevilla, the Baya, Pernambuco, Rio Geneyro, Buenosayres, San Iuan de Lua, Puertorico, Cartagena, Panama, and Lima, and wherever else boats arrived to sell captives” – who had the obligation to examine whether null baptisms had taken place, and to “examine, catechize, and baptize those Black people that bring Christian names, and ordinarily are not Christians.” Sandoval urged priests to meet ships as they arrived, before “[slave traders] commence to sell and distribute them [enslaved Africans] to different places.” This was necessary, he argued, because slave owners and priests in other regions of the Indies tended not to doubt the baptism of enslaved Black Africans, as they were persuaded that “having passed through the port they [enslaved people] will already have been baptized.” Sandoval stated that priests in ports should determine, as soon as ships arrived, whether enslaved Black Africans were “of Jesus Christ, and his church, and upon discovery that they are not, to ensure that they become so.” For such purposes, the Cartagena Jesuits trained a cadre of free and enslaved skilled African interpreters who aided in communicating with enslaved individuals of varied African linguistic backgrounds, noting that “if speaking to them through their languages and interpreters, we will judge by the responses that they give to the questions that we ask them.”Footnote 88

After experiencing the constant specter of death and brutality over the course of a forcible displacement through the Middle Passage, enslaved people on ships destined to Cartagena would then be forced to endure further torturous detentions when captains anchored their vessels for days or weeks in bays surrounding the port in an attempt to contain any infectious diseases onboard. That is when Sandoval and Claver or their African interpreters would row from Cartagena to the anchored ships to meet the captives and conduct extensive investigations into their religious knowledge that would determine their spiritual needs, principally whether or not they had been correctly baptized in African ports.Footnote 89 Upon reaching land, Claver would reportedly perform elaborate baptisms during which he was assured, through interpreters, that his enslaved flock understood the meaning of the baptism and wished to become Christians.Footnote 90 Had Francisco Martín encountered Sandoval and his African interpreters upon arriving in Cartagena – either while still on the ship or upon disembarking – Sandoval would have soon discovered that there was no need for an interpreter, for Martín spoke Spanish (and perhaps Portuguese too), and nor was there need for a baptism as Martín was well versed in the Christian faith. Martín may also have informed his Jesuit interlocutors that he was free and that his enslavement was illegitimate, because three months earlier, a Portuguese converso named Manuel Bautista Pérez had illegitimately purchased him from another Portuguese trader in the port of Cacheu in West Africa.Footnote 91 It is likely that Martín was listed as a Black ladino in an inventory compiled by Bautista Pérez that listed his trading activities in Cacheu in 1614.Footnote 92 However, he may well have been justifiably suspicious of priests in and around slave-trading ports, as he later recounted that his illegitimate enslavement had taken place at the hands of a priest named Manuel de Sossa on a beach in Sierra Leone.Footnote 93

Martín disembarked from the ship in June 1614 into what might ostensibly have been regarded as a Black city. Early seventeenth-century Cartagena de Indias served as the epicenter of the Atlantic trade in enslaved Black people who hailed from various regions of Upper Guinea and West-Central Africa. From there, merchants sold slaves for onward journeys to Lima, Panama, and New Spain, while other enslaved Africans remained in Cartagena or were displaced inland to New Granada.Footnote 94 The port city thus comprised a large, transient population of enslaved Black people. In addition, Cartagena’s urban landscape was composed of enslaved Black people laboring in private households, free Black vecinos, and increasingly large communities of Black fugitives in the hinterlands, who established palenques and maintained ties with enslaved and free Black populations in urban centers.Footnote 95 The large Black population of the port – especially the free individuals – also caused concern among royal officials and Spanish vecinos. A tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition was established in Cartagena in 1610, mainly to police Black ritual healing practitioners, especially women.Footnote 96 The port also served as a major crossroads for travelers between Castilla and the Spanish Americas, who included free Black individuals who sojourned in Cartagena while organizing their onward journeys.Footnote 97

The world of commerce, slave trading, and policing of Catholic religiosity in Cartagena de Indias was not unfamiliar to Martín. Cartagena as a key port city in the transatlantic slave trade occupied a similar position to that of his native Cacheu during the previous half-century. As Sandoval described in 1627, following interviews with enslaved Africans, slave traders, and priests, “[Cacheu] is the most important port of all of Guinea. Ships from Sevilla, Portugal, the island of Santiago and many other places come here to trade in Black slaves and many other things”; he also noted that Cacheu had “a trading port, market, and church, which has a priest appointed by the king.”Footnote 98 Martín had been born in the Cacheu household of a Portuguese captain to free Black parents who hailed from the Zape nation and Cabo Verde, and would later testify to knowing most of the Portuguese converso merchants who resided in that port and those who passed through on slave-trading ventures.Footnote 99 It is possible that Martín formed part of the Kriston community in Cacheu – otherwise known by the Portuguese as Christianized Africans – who came to play a prominent role in facilitating trade and commerce between European traders and different African rulers; Martín and his African witnesses argued that his parents were well known as free Black Christians in Cacheu.Footnote 100

Martín also testified that he labored as a wage-earning grumete on Portuguese ships along the coasts of Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Gambia.Footnote 101 Historian Philip Havik defined the grumetes of Cacheu as “Kristo rowers, pilots, interpreters, and petty traders, who acted simultaneously as traders and brokers, negotiating with African and Atlantic actors, whose existence therefore depended and thrived on making themselves indispensable.”Footnote 102 Havik pointed out that Kriston actors such as grumetes and tungumás (free Christian women from coastal ethnic groups) “formed an internal African trading diaspora that scouted the coast for commodities, while building and mediating extensive patron–client relations with local African elders and chiefs along its shores.”Footnote 103 Indeed, as a wage-earning grumete on Portuguese slave-trading fleets in Guinea and in Sierra Leone, Martín came into contact with a wide array of Europeans and Africans who traveled to and traded in Castilla, Portugal, the Indies, and Africa, in addition to enslaved Africans who were forcibly displaced from African shores to the Americas.Footnote 104 Exemplary of such relationships, Martín testified that Antonio Rodríguez, the captain of the ship in which Martín had been forcibly displaced from Cacheu to Cartagena, had known him for many years as a free man in Cacheu, while he claimed to know three other Spanish merchants or captains who arrived in Cartagena between June 1614 and March 1615 from his time in Cacheu and Sierra Leone.Footnote 105

Finally, Martín would not have been surprised by the presence of priests in Cartagena de Indias, nor by the reach of the Holy Office of the Inquisition that had recently been established in the port. He was intimately acquainted with Iberian Catholicism. In Cacheu and the surrounding locales, inquisitorial investigations into residents – both Black Christians and Portuguese conversos – had been active since 1540 (just four years after the establishment of the Holy Office of the Inquisition in Lisbon).Footnote 106 Inquisitorial authorities persecuted Black Christian women for ritual healing practices there, much as Inquisitors would do in Cartagena after 1610.Footnote 107

Martín thus arrived in Cartagena in 1614 with significant knowledge of the Atlantic world, Iberian laws, and Atlantic commercial systems, and well versed in the meaning and significance of a Christian profession of faith in the early Iberian Atlantic. But he also arrived in a port city where residents possessed intimate knowledge and awareness of well-established Christian pockets in Africa.Footnote 108 Sandoval, the Cartagena-based Jesuit who had spent his career investigating enslaved Africans’ places of origin, recognized that some Black Christians lived in Cacheu, as he noted that “many people have been successfully baptized here,” but he offered a word of warning that “these Black Christians have little knowledge of Christianity and interact with gentiles. This means they easily return to rites that are not part of our faith.”Footnote 109 However, as I argue elsewhere, Sandoval weaponized the history of Catholic conversion by kingdoms in West Africa and West-Central Africa, and legends about the establishment of a glorious ancient Ethiopian Church, which he argued that God had chosen as the first Christian church, in order to justify the mass enslavement of all Africans and their removal from Africa to the New World in the name of the establishment of a Black elected church.Footnote 110

Martín’s arrival in Cartagena also tells a story of connections between enslaved and free Black people dwelling in the city who maintained knowledge and memories of Cacheu and Upper Guinea. As his captors disembarked him from the ship, Martín reportedly encountered Pedro de Tierra Bran.Footnote 111 Pedro, a forty-five-year-old free Black Christian who resided in Cartagena, testified to recognizing Martín, for he had previously dwelt in the same house in which Martín had grown up in Cacheu. In their conversation, Martín informed Pedro that he was to be sold as a slave in the port. Pedro reportedly expressed disbelief, saying that Martín could not be sold, for he was a free man. Another figure who is reported to have recognized Martín as he disembarked from the ship was Sebastián Barroso, a thirty-year-old free mulato and merchant (tratante) who resided in Cartagena. He later explained that he had known Martín for sixteen years, and claimed to have sojourned in the captain’s house in Cacheu for six years a decade earlier, before Barroso traveled to Cartagena. Barroso and Pedro were two of seven free and enslaved Black individuals in Cartagena who testified – in 1614, within three months of Martín’s arrival – to knowing Martín as a freeborn person in Cacheu or on fleets across West African coasts prior to their arrival in Cartagena some years earlier. Some of the witnesses had been brought as slaves from Cacheu, while others reported that they traveled to the New World as free men or women.Footnote 112

On July 4, 1614, one month after arriving in Cartagena, Martín presented a petition to the justice of the city for freedom on the basis that his enslavement was illegitimate. Presiding over the case was Luis de Coronado, the teniente general (chief legal counsel) of the governor of Cartagena.Footnote 113 Martín explained that he was from Cacheu in Guinea and the son of Antón Martín, born in Cabo Verde, and his wife named Elena, of the Zape nation. He described how he and his parents were “free people and Christians” who had lived in Cacheu in the house of a Portuguese captain.Footnote 114 According to Martín’s testimony, about eight and a half years earlier, in 1606, he had left Cacheu for Sierra Leone to labor on a ship as a wage-earning grumete for a Cacheu-based captain named Ambrosio Dias. Martín recalled that after about four years Dias sent him to the “beach of the sea” with a letter for a cleric named Manuel de Sossa. There, on the shore, they “tied my hands and put me on a ship and took me to Cacheu to the house of Juan Méndez.”Footnote 115 Martín recalled that Méndez had attempted to sell him to Antonio Rodriguez, the captain who eventually brought Martín to Cartagena. According to Martín, Rodríguez had refused to purchase him since the captain knew he was a free man. Thereafter, Méndez sold Martín to a Portuguese converso named Manuel Bautista Pérez, who took Martín to Cartagena on Rodríguez’s ship along with his other enslaved cargo. It was only after arriving in Cartagena, Martín noted, that Bautista Pérez branded his body with a hot iron to mark his status as a slave. He pleaded that the Cartagena court would recognize that “being free of free parents, and there not having been cause or title nor reason why for having been free and having been born free that I have come to this servitude,” and asked that the court grant him freedom on the basis that his enslavement was illegitimate.Footnote 116

In his litigation, Martín and his aforementioned procurator, Francisco Gómez, presented an argument for the illegality of enslaving “between Christians.”Footnote 117 Gómez argued that even “in the case that [Martín] had been sold one hundred times,” such an occurrence “could not harm his natural right” to freedom because Martín was the:

son of free parents and he has been brought up and lived as a free man, and it is not legal (no consta, ni puede constar) that he [Francisco Martín] has become enslaved (cautivo) in a just war, or even an unjust war, nor that he has been sold by his parents, nor [enslaved as punishment] for a crime that he might have committed because there is no right [law] (no hay derecho) to enslave between Christians for any of these reasons.

Martín’s argument therefore relied on the fact he was already a Christian in Cacheu, and that it was illegal for a Christian to enslave a fellow Christian for any reason.

A number of possibilities explain why the case was heard and eventually won, not just in Cartagena, but also on appeal in the higher court of the Real Audiencia in Santa Fé (in present-day Bogotá) the following year. The first possibility is a general concern in Cartagena that free Black people were being illegitimately enslaved in West Africa. As noted earlier in the chapter, Gómez, Martín’s legal defender, proposed such a possibility.Footnote 118 Hushed discourses also existed among Black residents of Cartagena about the legality of slavery and the possibilities for legal and extralegal routes to obtain freedom among Black city dwellers. In this period, a number of enslaved Black people litigated for their freedom in Cartagena, not because of illegitimate enslavement, but because of unduly harsh physical violence by their enslavers.Footnote 119 In addition, there was the presence of palenques in the hinterlands and the seemingly fairly common aspiration – as documented by Larissa Brewer-García, Jane Landers, Kathryn J. McKnight, María Cristina Navarrete Peláez, and Ana María Silva Campo – among enslaved Black city dwellers to flee to them in search of freedom.Footnote 120 These scholars have explored how royal officials’ interviews with former residents of the Palenque del Limón and the Matudere Palenque – two maroon communities that Cartagena officials destroyed in 1634 and 1693, respectively – shed light on the emergence and circulation of alternative ideas about governance and freedom among enslaved and free Black individuals in seventeenth-century Cartagena. Such ideas often disregarded Castilian legal codes and involved collective acts of resistance. In particular, these scholars have traced the ties that residents of palenques in the hinterlands often maintained with Black port dwellers in Cartagena, suggesting a constant circulation of information and ideas about alternative and illicit forms of governance and the means by which they could experience different forms of freedom from slavery.

Martín’s ability to command free and enslaved Black witnesses who claimed to know him from Cacheu also attests to the existence of discourses about legal and extralegal means of evading slavery in Cartagena. Certainly, Martín’s owner, Manuel Bautista Pérez, posited exactly this theory in the trial: He claimed that it was well known in the city that “the Black people conspire to free one another by providing false testimonies.”Footnote 121 Further, upon arriving in Cartagena de Indias, Martín dwelt in a townhouse with his owner and with at least two other enslaved Black people, who may or may not have arrived on the same slave ship as Martín. As criminal trials and other Black Cartageneros’ freedom suits of the period demonstrate, city dwellers were often intimately connected to the business and affairs of their neighbors.Footnote 122 Word of Martín’s litigation might have spread rapidly among Black residents in the port. Certainly, in the house where Bautista Pérez resided, Martín would have had daily relationships with other servants and slaves and with other neighborhood residents, apart from when his owner restricted his movements by incarcerating him in chains and giving him life-threatening physical injuries.Footnote 123 Perhaps such daily interactions – even if infrequent owing to Bautista Pérez’s harsh violence and imprisonment – were how Martín gathered his witnesses.

A coterie of Black and mulato witnesses from West Africa (and one from Portugal) who resided in Cartagena either in captivity or as free individuals testified to knowing Martín in Guinea and communicating with him in Cartagena in the three months since his arrival (witness testimonies were presented in late August 1614). These statements demonstrate the existence of a discourse among Black port dwellers about the illegitimacy of enslaving free Black Christians: The witnesses argued that Martín’s enslavement was illegitimate because he was a free Christian in Guinea.Footnote 124

The previously mentioned forty-five-year-old Pedro de Tierra Bran, for example, who described himself as a free Black Christian, explained that he knew Martín from Guinea. Before Pedro had traveled to Cartagena seven years earlier, he had spent fifteen years residing in Cacheu and had worked as a servant in the house of a Portuguese captain. There, Pedro had seen Martín living with his parents – both free Christians – and described how he saw them “have and possess their liberty.” He explained that Martín had labored on ships in Tierra de Zoala and in Tierra de Cape, serving “white masters” who treated and paid him as a “free person born to free parents.” A fifty-six-year-old free mulato named Domingo Morrera, a resident of Cartagena who was born in Tavira (Portugal), recalled that when he was laboring as a ship pilot in Guinea some twelve or thirteen years earlier, he had worked alongside Martín on a ship in Cacheu. Morrera recounted that he had seen Martín laboring for a wage as a grumete and that the entire crew considered Martín to be a free person. Another witness named Francisco, who was from Cabo Verde and enslaved to a ship captain in Cartagena, explained that he knew both Martín and the slave trader Bautista Pérez. Francisco described how he had been enslaved and forcibly displaced from Guinea to Cartagena eight years earlier and testified that he had known Martín for six or seven years during the time he lived in Cacheu. He stated that he had been brought up in those lands, and thus had known Martín since he was very young and living in the captain’s house, “always seeing that he [Martín] lived and was reputed as a free man.” Francisco added that he would have heard if Martín had been enslaved because “the land of Cacheu is very short,” implying perhaps that news of residents’ lives traveled fast.

A key question regarding this illegitimate enslavement concerned when and where Martín had been subjected to the physical branding of his body, thus marking his status as a slave. According to Martín, it was only upon arriving in Cartagena and hearing that he might litigate for his freedom that Bautista Pérez had branded his initials on Martín’s chest with a hot iron. Three of Martín’s witnesses attested that the branding occurred in Cartagena and not in Guinea. Barroso stated that Martín had not been branded when he disembarked from the ship, but that a few days later he saw him with a “mark of fire on his chest.” Martín’s seven witnesses attested to the common practice of branding captives in Guinea prior to their embarkation on ships, and assured the court that slave traders were prohibited in Guinea from branding free Black Christians as slaves. Another witness named Manuel, who had testified that he had been brought as a slave from Cacheu to Guinea some years earlier, explained that he knew that slaves were branded in Guinea because this had happened to him before he was displaced to Cartagena, and that he knew “they did not brand free people there [Guinea].”

Bautista Pérez refuted Martín’s claim that he had been illegitimately enslaved. He explained that Martín had previously been enslaved to many other Portuguese traders in Guinea, and that he had purchased him from a Portuguese slave trader based in Cacheu named Juan Méndez Mezquita to settle the 150 pesos that Méndez Mezquita owed Bautista Pérez.Footnote 125 Bautista Pérez argued that Martín’s litigation in Cartagena was calculated. Sufficient structures of justice existed in Cacheu, argued the irate slave owner, for Martín to have pursued his freedom there had he believed that his former owners had illegitimately enslaved him. The slave trader’s witnesses confirmed that courts where enslaved people could seek justice did indeed exist in Cacheu, and reported that other free Black individuals in the Guinean port litigated there if they were illegitimately enslaved. Bautista Pérez also denied that Martín had been branded in Cartagena, instead asserting that this had taken place “with the rest of his Blacks” in Cacheu. The slave trader’s witnesses confirmed this assertion.

Bautista Pérez also questioned the legitimacy and credibility of Martín’s Black witnesses. On September 29, 1614 – one month after Martín had presented his witnesses – Bautista Pérez argued that his case was stronger because his witnesses were honorable men of great faith and credit who had resided in Cacheu for many years. In contrast, he argued, Martín had not proved anything because his Black and mulato witnesses “have no faith or credit.” He alluded to widespread knowledge in Cartagena that because these Black people were of the same nation, “they say untruths and they are ignorant people who do not understand their oaths because of their incapacity.” Finally, Bautista Pérez suggested that a conspiracy existed among Black dwellers of Cartagena to help each other obtain freedom by providing false witness testimonies.

After the court ruled in Martín’s favor in November 1614, pronouncing him as a free man who had been illegitimately enslaved, Bautista Pérez presented an appeal in which he transformed the legal argument from a debate about the legitimacy of enslavement on the basis of Christianity or lack thereof to a juridical argument concerning just war.Footnote 126 On appeal, in November 1614, he recalled that two and a half years earlier, Martín had labored as a grumete on a ship owned by a Cacheu-based captain named Juan Méndez Mezquita. The crew comprised Black and white laborers who were tasked with recovering Black slaves who had been captured by “negros de guerra (Black people of war),” defined by Bautista Pérez as groups of Black people who “spend their time waylaying and robbing ships” on the coasts of Guinea to steal merchandise and ransom any enslaved Africans and crew on the ships to European merchants. Bautista Pérez explained that during the expedition, the negros de guerra overpowered Méndez Mezquita’s ship, killing the captain and pilot and imprisoning the white and Black sailors, and enslaving the Black slaves and free men alike. It was at this moment, he argued, that Martín became enslaved – during a just war at the hands of the negros de guerra. According to Bautista Pérez, a Portuguese Cacheu resident named Enriquez Hernández recovered the captured ship and crew and negotiated ransom prices that would ensure the release of the captives. He posited that Martín was thus legitimately enslaved as he had been captured in a just war. Further, it was Martín’s previous employer, Méndez Mezquita, who had provided Hernández with the 150 pesos for Martín’s release, meaning that ownership of Martín was transferred to Méndez Mezquita. Thereafter, Bautista Pérez explained, Martín served as a slave in Méndez Mezquita’s household in Cacheu, that is, until he was sold to Bautista Pérez.

The legal arguments presented in the case were therefore transformed from a discussion of the illegitimate enslavement of free Black Christians to the legitimacy of slavery through just war. All the while, Martín and his witnesses stood their ground, and argued that as a free Black Christian he could not be enslaved under Castilian laws of slavery, nor legitimately purchased as a slave. Responding to the appeal on February 20, 1615, Martín agreed that he had indeed labored as a grumete for Méndez Mezquita, but noted that he had done so as a free man who earned a salary “like the other free people.”Footnote 127 He also agreed that one day some negros de guerra had captured the entire ship. Martín explained that they killed the captain and the pilot and tied up the remaining enslaved cargo and the free Black and white laborers onboard the vessel. However, he refuted the notion that the capture of the Portuguese ship meant that a just war had taken place. Martín agreed that Hernández had paid a ransom for him and the crew, but denied that he had been enslaved. Instead, he explained how upon returning to Cacheu, he and Méndez Mezquita signed a contract specifying that Martín would labor for him as a wage-earning grumete for two more years. Martín explained how later, while traveling toward Gambia, he managed to escape an English raid in a town where he was based and had returned to Méndez Mezquita’s abode in Cacheu. Thus, even though Martín acknowledged that he had been captured by negros de guerra and was subsequently freed through a ransom paid by a Portuguese merchant, he positioned such an event in terms of his capture and rescue alongside other free white wage-earning sailors. He subsequently agreed to continue laboring for Méndez Mezquita, but with a time-specified labor contract as a wage-earning grumete.

The ruling by Luis de Coronado in Cartagena on November 22, 1614, that Martín was “free and not subject to captivity or servitude,” along with the order that Bautista Pérez allow Martín “to enjoy (gozar) his liberty” without imposing any impediments, is especially surprising because of the weight that it gave to Martín’s Black witnesses over those presented by Bautista Pérez.Footnote 128 In Cartagena, as in Guinea, Bautista Pérez interacted with trading associates who were part of his extended network belonging to the New Christian Portuguese diaspora.Footnote 129 Indeed, the witnesses who attested to Bautista’s ownership of Martín on July 7, 1614 were slave traders ready to depart from Cartagena to Spain.Footnote 130 All six were vecinos of Portugal. They testified that they had spent time in the port of Cacheu during the previous decade and knew Martín there, while agreeing that Bautista Pérez was an honorable man of Christian faith who would never purchase or illegitimately enslave a free man.

Coronado’s ruling and his favoring of the testimonies provided by enslaved and free Black people in Cartagena suggests that debates and doubts regarding the legitimacy of the enslavement of some Black people existed among royal deputies in Cartagena de Indias. His decision also paralleled the legal precedents described by the procurator, Francisco Gómez, who had stated that many similar legal cases regarding illegitimate enslavements had been previously heard in Cartagena courts and had resulted in the courts setting litigants free.Footnote 131 The ruling also dismissed Bautista Pérez’s request to present evidence that Martín’s witnesses were unreliable, untrustworthy, reputed as drunks, and were engaged in a conspiracy in Cartagena to free enslaved Black Africans. Similarly, his appeal based on just war and his legitimate purchase of an already enslaved person also failed. On March 17, 1615, Luis de Coronado decreed that his initial ruling, in which he had freed Martín, was final.Footnote 132 He referred the case to the Real Audiencia in Santa Fé for final sentencing and ordered both parties or their representatives to appear in that court four months later. The Real Audiencia considered the case on July 7, 1615, and by November 13, 1615, the court had reiterated Luis de Coronado’s ruling of November 28, 1614, with the added clause that Martín should serve the person who paid his ransom for one year, thereby confirming his freedom while potentially subjecting him to another year of servitude to Bautista Pérez (although the ruling is ambiguous as to whether Martín had already served the year).Footnote 133 By May 10, 1616 – nearly two years after Martín initiated his petition in July 1614 – the Real Audiencia asked for both parties to be notified of the final decision.