Introduction

At first glance, ship captains Andreas Mulder and Mathys Andriesz had much in common beyond their occupation. Both were born in 1736 and appeared in archival records in 1779 and 1781, respectively, at the ages of 43 and 45. Both hailed from Denmark: Mulder from the island of Rømø off the coast of Jutland, and Andriesz from the village of Oksby, some 60 kilometers further north along the same coastline. They were both married and had left their native country to settle in the Dutch Republic, specifically in Amsterdam. Mulder had emigrated at 36, while Andriesz had made the move much earlier, in his mid-twenties. What set them apart, however, was their sense of allegiance. Mulder identified with his newly adopted country, recognizing the States General of the Netherlands as his authority. Andriesz, by contrast, maintained his loyalty to the King of Denmark, preserving ties to his homeland that Mulder had seemingly relinquished. This article focuses on immigrants in the late eighteenth-century Dutch Republic to explore why some, like Andreas Mulder, identified with their adopted country, while others, like Mathys Andriesz, did not. What factors shaped the national identity of early modern immigrants, and how were these allegiances formed and expressed?

When we shift from the eighteenth century to the present day, the notion of national identity, especially within the context of immigration, is a subject of intense debate (cf. Skrivanek Reference Skrivanek and Kraler2022). This is particularly true of the integrative dimension, which emphasizes the connection immigrants develop through cultural, social, and civic engagement with their host country (Citrin and Sears Reference Citrin, Sears, Abdelal, Herrera, Johnston and McDermott2009; De Figueiredo and Elkins Reference De Figueiredo and Elkins2003). From this angle, national identity – or host-country identification – frequently emerges as a contentious measure in public and political discourse, shaping perceptions of the “ideal migrant” as one who exhibits loyalty to their new country and integrates seamlessly into society, versus the “problematic migrant,” whose connections to their country of origin are seen as hindrances to successful incorporation (cf. Bloemraad et al. Reference Bloemraad, Esses, Kymlicka and Zhou2023). This dichotomy provokes important questions about the significance of patriotism and belonging in the migrant experience. Yet, despite its importance, host-country identification – “host-country patriotism” is a term also used for this phenomenon – remains underexplored in academic research. A notable exception is the seminal article by Reeskens and Wright (Reference Reeskens and Wright2014), which used data from 2008 to examine both the level of attachment immigrants feel toward their host country compared to non-immigrants and the factors influencing this sense of belonging.

When considering host-country identification from a historical perspective, this study represents, to our knowledge, the first systematic exploration of this theme among immigrants during the early modern period. Since the 1980s, it has become widely recognized that long-distance, cross-border migration was as characteristic of early modern society as it is today (Lucassen and Lucassen Reference Lucassen and Lucassen2009). Estimates of international migration flows even suggest that in some of the most economically advanced regions of early modern Europe – particularly the Dutch Republic – the levels of immigration were comparable to those observed today (Lucassen and Lucassen Reference Lucassen and Lucassen2009; Van Lottum Reference Van Lottum2007). Mulder and Andriesz were indeed two of many. The growing interest in early modern cross-border migration in the last decades has led to a variety of scholarly approaches, including studies on its linguistic consequences (Hendriks et al. Reference Hendriks, Ehresmann, Howell and Olson2018), cultural exchanges between immigrants and host societies (Heerma van Voss and Roding Reference Heerma van Voss and Roding1996), the determinants of migration flows (Klein and van Lottum Reference Klein and van Lottum2020), and the reception of immigrants in their new environments (Lucassen Reference Lucassen, de Munck and Winter2012). However, while the development of national identity in pre-industrial, especially eighteenth-century, European society has been the subject of extensive research (Jensen Reference Jensen2016, Reference Jensen2017), the specific attachment of immigrants to their host societies has, until now, received little to no attention. Even in recent studies that focused on reconstructing identity formation in premodern Europe (e.g., Kersting and Wolf Reference Kersting and Wolf2024; Prak Reference Prak2022), immigrant patriotism plays a marginal role.

The limited focus on early modern immigrants’ identification with their host societies is understandable. Unlike modern studies that rely on surveys and questionnaires, such tools are generally unavailable for the pre-industrial period. This article utilizes the Prize Paper Dataset (PPD), a unique eighteenth-century archival source that contains individual-level data relevant to host-country identification (Van Lottum et al. Reference Van Lottum, Lucassen, Heerma van Voss and Unger2011; Van Lottum Reference Van Lottum2015). The short biographies of the two Danish seamen above are derived from this dataset. The PPD stems from interrogations of thousands of seamen captured by the British Navy to determine whether seized vessels were lawful prizes. These interrogations not only document details about ships and cargo but also provide biographical information on the sailors, such as age, place of birth and residence, marital status, and rank. The PPD has, among others, been used to study migration determinants (Klein and van Lottum Reference Klein and van Lottum2020), labor productivity in shipping (Van Lottum and Van Zanden Reference van Lottum and van Zanden2014), and migration flows in eighteenth-century Europe (Van Lottum Reference Van Lottum2015). In this article, we focus on a previously unexplored aspect: the prisoners’ responses to the question of whom they regarded as their sovereign. This variable sheds light on immigrant workers in the Dutch Republic, revealing that while some remained loyal to their sovereign of birth, others shifted allegiance to local authorities such as the States General or the Prince of Orange and, after 1795, the new revolutionary regime. Our analysis covers the period 1776–1801, reflecting both the chronological bounds of the dataset and the broader institutional shift marked by the collapse of the Dutch Republic and the rise of the Batavian state. By analyzing these data, we aim to provide fresh insights into how these individuals navigated their loyalties and identities, offering a new perspective on immigrant identification and the factors influencing their allegiances in the early modern period.

This study contributes to several bodies of literature, including research on immigrant integration, the history of national identity, and early modern legal and maritime institutions. At the same time, it takes an intentionally exploratory approach, using a small but unusually rich dataset to test the applicability of modern identity concepts in a pre-modern context. Rather than offering definitive claims, the article examines how immigrants themselves articulated sovereign affiliation in ways that complicate both modern and early modern models of national belonging. In doing so, it opens up new avenues for investigating patriotism, civic membership, and identity formation in a period where such categories were in flux.

This article is organized into five sections. In the section “Migrants to the Dutch Republic,” we begin by exploring the central subject of our study: immigrant workers in the Dutch Republic. The section titled“Allegiance and civic belonging in the Dutch Republic” turns to the broader debate on national identity, civic membership, and allegiance in the early modern world. Section “Data and validity” outlines the data and validates their reliability for studying allegiance. The “Patterns of allegiance: Determinants of host-country identification” section presents the results of our analysis, drawing on the dataset to identify patterns and determinants of host-country identification. Finally, the “Conclusion: Allegiance before nationalism” section concludes with a discussion of how these findings enrich our understanding of identity formation in pre-modern migrant communities.

Migrants to the Dutch Republic

By the seventeenth century, the Dutch Republic had become a significant center of attraction for migrants across Europe (Janssen Reference Janssen2017). The cities of Holland, in particular, emerged as magnets for these immigrants, driven by the region’s unique combination of relative religious tolerance and robust economic growth (Lucassen and Lucassen Reference Lucassen and Lucassen2017, Reference Lucassen and Lucassen2018; Van Lottum Reference Van Lottum2007). Religious refugees, seeking a haven from persecution, found a comparatively safe refuge, while labor migrants were drawn to the booming economy, which offered high wages and abundant job opportunities. Migrants played an essential role in nearly all sectors of the economy, often constituting a significant or even majority share of the workforce. The building industry, service sectors, textile production, and especially the expanding maritime industry relied heavily on foreign labor (De Vries and Van der Woude Reference De Vries and Van der Woude1997). Large numbers of migrants, particularly from Northwestern Europe, made their way to the Republic (Van Lottum Reference Van Lottum2007, Reference Van Lottum2011). This diverse and dynamic labor force forms the backdrop against which we situate our study of allegiance and host-country identification.

In the century that followed, the number of religious refugees that sought a safe haven in the Netherlands dwindled. The tens of thousands of Huguenot refugees that arrived here after the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 belonged to the last major wave of refugees settling in the Dutch Republic. Although by the beginning of the eighteenth century the economic boom times of the first half of the seventeenth century lay far behind, the influx of labor migrants remained substantial (Van Lottum Reference Van Lottum2011). While religious motives declined, economic incentives – especially in maritime employment – continued to drive cross-border migration.

In particular, the Dutch shipping sector remained resilient to the economic stagnation that hit the Dutch Republic (Van Lottum Reference Van Lottum2007). While many sectors of the economy, most notably the textile and building industries, witnessed a change in their economic fortunes after the 1670s, the maritime sector continued to expand throughout the eighteenth century: notably, intra-European shipping grew well into the early 1790s. More generally, compared to other European countries, institutional barriers to foreign workers were low in the Dutch Republic, facilitating immigrants’ entry into various sectors (Lucassen Reference Lucassen, de Munck and Winter2012). This openness was especially pronounced in the maritime sector, where pragmatic economic policies prioritized operational flexibility and skilled labor over restrictive national preferences (Van Lottum et al. Reference Van Lottum, Lucassen, Heerma van Voss and Unger2011). Consequently, the share of foreign crew aboard Dutch ships rose steadily: around 1700, about 40 percent of common sailors came from abroad; nearly a century later, this had risen to more than 60 percent (Van Lottum Reference Van Lottum2015). Among the officer class, including ship captains, this share was somewhat lower but still substantial: approximately 25 percent were foreign-born.

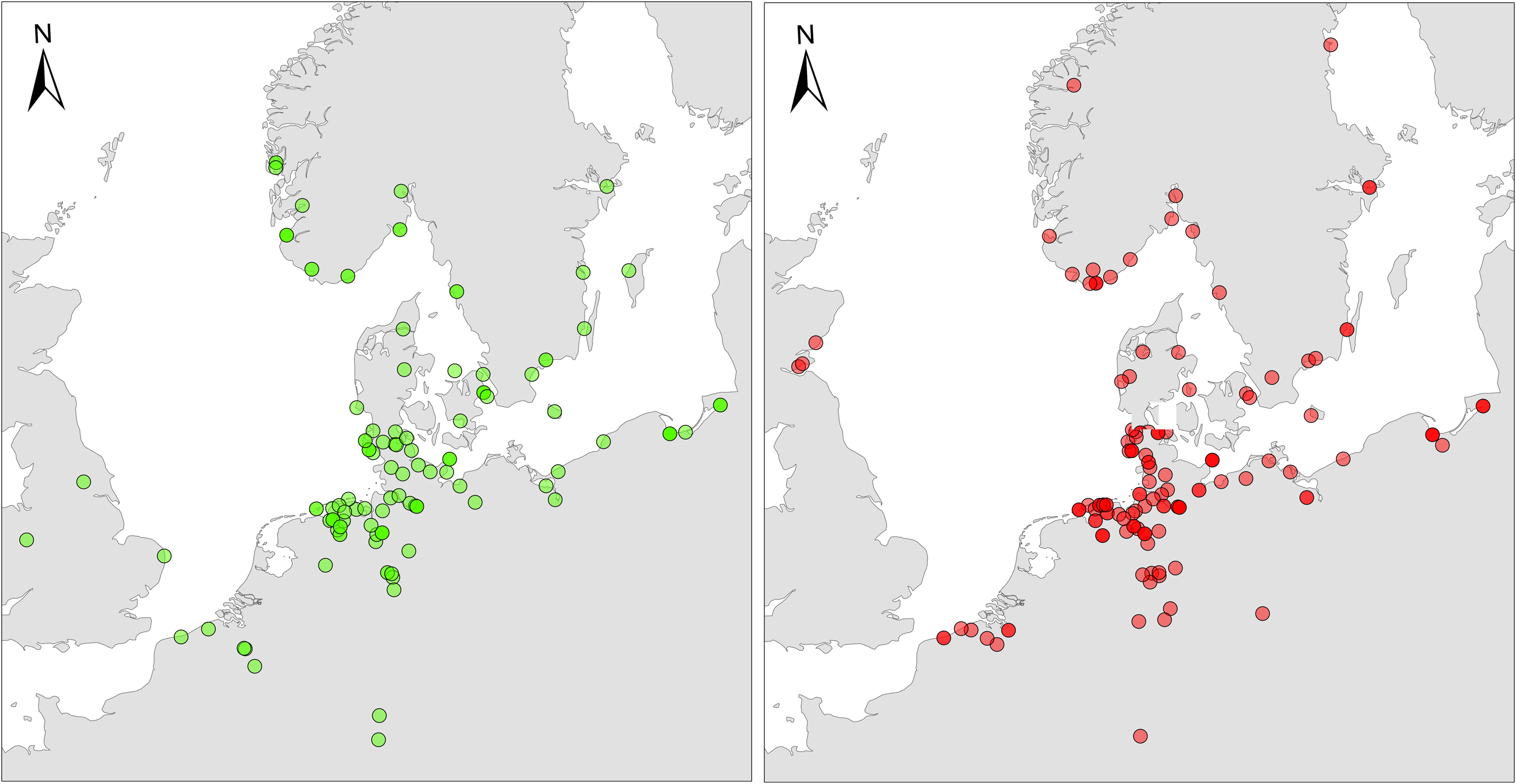

Most immigrant workers with ties to the Dutch Republic in the late eighteenth century originated from countries bordering the North Sea and the Baltic. The heatmap we generated using data from the PPD (Figure 1) highlights that migrants working aboard Amsterdam and Rotterdam ships primarily hailed from the German states, not only the maritime regions in the north but also the Rhineland, as well as the Southern Netherlands (present-day Belgium), southern Sweden, Norway, and Denmark – in particular the western coastal region where Mulder and Andriesz grew up. While this broad geographic spread confirms the international character of Dutch shipping, it also raises questions about how immigrants from such diverse backgrounds navigated identity and allegiance in their host society. Furthermore, the international nature of this workforce threatens to obscure the complexity of individual migrant experiences. While some migrants established long-term residence in the Dutch Republic, others maintained more transient connections, returning to their home country after serving aboard a Dutch ship or working for foreign employers while residing in the Republic.

Figure 1. Regional origins of maritime migrants to Amsterdam and Rotterdam, late 18th century.

Note: Kernel-density shading by color: density increases from dark green → light green → yellow → orange → red; reds/oranges mark the highest concentrations, greens the lowest.

In this study, we will focus specifically on migrants who became residents of the Dutch Republic. Their deeper socioeconomic and civic integration provides a clearer lens through which to examine shifts in national identity and loyalty. By analyzing their responses regarding allegiance from the Prize Papers, we uncover the factors that either facilitated or hindered their identification with their host country. This approach offers a rare and valuable insight into the dynamics of immigrant patriotism in early modern Europe. The following section turns to the broader conceptual framework, tracing how allegiance and civic membership have been understood in both historical and theoretical literature.

Allegiance and civic belonging in the Dutch Republic

In 1778, David Jacobs, a boatswain from the German island of Borkum and residing in Amsterdam, was questioned by a clerk from the High Court of Admiralty. Alongside standard personal details – such as place of birth and residence, his age (he was 39), and marital status (he was married) – Jacobs was asked to declare his sovereign. Rather than a straightforward response, Jacobs provided a detailed account of his changing allegiances: “untill he was seven or eight years of age,” he explained, “he was a subject to the king of Prussia [and] afterwards became a subject to the emperor of Germany and is now a subject to the States General of the United Provinces.” (The National Archives (TNA), High Court of Admiralty (HCA) 32/385).

The following year, another seaman, the 28-year-old Hannoverian Jan Pranger, also conveyed his sense of allegiance but offered additional context. “He hath navigated with the Dutch these six years last past,” Pranger explained, and “holds himself now a subject to the States General” (TNA, HCA 32/422). Similarly, Harman Emling, from the village of Asel in Ostfriesland, reported shifting his allegiance to the States General, justifying his decision with personal circumstances: “he hath been married about four years, and his wife resedes in Amsterdam in Holland” (ibid.).

Most respondents, however, were not as elaborate as these three men from northern Germany. In 1777, Roelof Eversz, who lived in Amsterdam but was originally from Arendal in Norway, simply stated that he was “born a subject of the King of Denmark but is now a subject of the States of Holland” (TNA, HCA 32/417). For those who had not experienced a shift in allegiance, responses could be even more concise, often limited to a straightforward “King of Denmark.” Captains Mulder and Andriesz, with whom we started this article, provided similarly concise answers.

These testimonies offer valuable insight into how allegiance was conceptualized and expressed in the late eighteenth century. Where earlier historiography often portrayed national identity in this period as either weak or embryonic, more recent work has shown that claims of affiliation and belonging were common and publicly meaningful – even if the modern nation-state had yet to emerge (Jensen Reference Jensen2016; Prak Reference Prak2022).

Classical theories of nationalism have long viewed the emergence of national identification as a product of modernity, emphasizing the role of industrialization, state centralization, or mass media (Anderson Reference Anderson1983; Gellner Reference Gellner1983; Hobsbawm Reference Hobsbawm1990). In this framework, early modern allegiances appear weak or anachronistic, often portrayed as purely local, dynastic, or religious. But this perspective is increasingly challenged. Recent work on the “pre-history” of nationalism has demonstrated that forms of territorial identification and patriotic sentiment circulated widely in early modern Europe (Breuilly Reference Breuilly1993; Jensen Reference Jensen2017; Thiesse Reference Thiesse2022).

These ideas were not uniform and varied considerably by region and political context, but they suggest that categories such as “sovereign,” “nation,” or “homeland” could carry meaning for individuals like Jacobs or Pranger. As Prak (Reference Prak2022) emphasizes, civic identity in early modern Europe was typically rooted in local institutions such as guilds, militias, and urban governance. Although institutional barriers certainly existed – Jews were almost universally excluded, and Catholics frequently faced significant restrictions – these venues nonetheless offered many migrants viable pathways to civic integration (Lucassen Reference Lucassen, de Munck and Winter2012). Local citizenship (burgher- or poorterschap), granted by cities rather than central authorities, generally required payment, proof of residence, and sometimes guild or militia membership. Yet compared to other European polities, the Dutch Republic maintained relatively open institutional structures, especially in the maritime sector, where labor demand remained high. This accessibility was further enhanced by the fact that most labor migrants – particularly in shipping – originated from Protestant regions, making them more eligible for civic incorporation and smoothing their integration into the fabric of urban life.

At the same time, the articulation of allegiance in our sources suggests that identity could be dynamic and cumulative. For some migrants, like Jacobs, identification with a new polity was not a sharp break but an accumulation of experiences, each layered upon earlier affiliations. Such a perspective complicates both traditionalist views that see national identity as inherently rooted in fixed cultural-linguistic traditions and modernist accounts that treat it as a product of mass politics alone. Instead, it presupposes a more constructive interpretation of identity formation, one that stresses context, choice, and the role of institutions.

Moreover, the concept of “host-country identification,” while rooted in contemporary social science, offers a useful lens for examining these early modern expressions of allegiance. As Reeskens and Wright (Reference Reeskens and Wright2014) suggest, host-country identification involves not only emotional attachment to a country but also the perception of oneself as a member of that society. In their analysis of early twenty-first-century European panel data, both individual-level factors (such as education or duration of residence) and broader societal contexts (such as integration policies) shape the strength of identification. Our study, while historical and more exploratory in nature, speaks directly to this framework: the declarations of allegiance recorded in the Prize Papers may be seen as antecedents of modern forms of civic identification, of course filtered through the legal, occupational, and domestic lives of early modern migrants.

Taken together, the declarations suggest that early modern migrants could and did articulate attachment to host polities in ways that resemble modern forms of host-country identification. These expressions of allegiance were not uniform, nor were they necessarily abstract or ideological. Instead, they were rooted in the material and social contexts of everyday life. David Jacobs’ careful enumeration of successive allegiances – from Prussia to the Holy Roman Emperor to the States General – demonstrates that these choices were often neither fixed nor accidental but negotiated across time and experience.

In the next section, we turn to the dataset in greater detail to examine how such declarations were recorded, why we regard them as methodologically robust, and what they reveal about the shifting contours of allegiance in the eighteenth-century maritime world.

Data and validity

The preceding discussion highlighted how allegiance in the late eighteenth-century Dutch Republic was not simply inherited or declared out of necessity but shaped through personal histories, civic integration, and the layered institutional fabric of early modern society. To further investigate how such allegiances were articulated and distributed among migrants, we now turn to a dataset of 288 individuals, all born outside the Republic but residing within it at the time of their capture. As Figure 1 illustrates, these men were drawn predominantly from the Holy Roman Empire and Scandinavia, comprising 63 and 27 percent of the sample, respectively, with the remaining 10 percent representing other European origins. Their testimonies, recorded during interrogations by British prize courts, offer rare and detailed insights into how migrants declared sovereign affiliation in a highly formal legal context. In the analysis that follows, we standardize and interpret these declarations to identify broader patterns in allegiance – while also situating them within the specific social and political contexts that may have shaped these choices.

To facilitate systematic analysis, the recorded declarations were standardized to align with present-day national borders. For instance, individuals naming the “States of Holland” or the “States General” were grouped under “the Netherlands,” while those who cited the King of Sweden or King of Denmark were recorded as “Sweden” or “Denmark,” respectively. The many German polities referenced – ranging from the King of Prussia to the Burgomasters of Hamburg – were coded collectively as “Germany.” In addition to allegiance, we extracted and standardized other variables embedded in the testimonies, including marital status, residence, rank aboard ship, and length of time spent in the Republic. These variables, some of which were only indirectly stated, allow us to explore how institutional integration, personal circumstance, and occupational standing may have shaped migrants’ sovereign affiliations. Many of these same variables have been used in earlier work on the Prize Papers dataset and thus provide a robust basis for both continuity and innovation in the present analysis.

The question of representativeness has been addressed in earlier research using the PPD (e.g., Klein and van Lottum Reference Klein and van Lottum2020; Van Lottum and Van Zanden Reference van Lottum and van Zanden2014). Although these records derive from a wartime legal process, there is little evidence that sailors were selected or questioned in ways that would introduce systematic bias. Van Lottum and Van Zanden (Reference van Lottum and van Zanden2014) found no significant skew in the composition of captured ships or crew profiles across time, lending confidence to the integrity of the data. Moreover, the interrogations themselves formed only a small component of a much larger evidentiary process. The court relied primarily on logbooks, manifests, and shipboard documentation seized at the time of capture – records that were often cross-checked against testimony. While some papers were occasionally destroyed to obscure affiliations, the interrogations served largely as corroborative instruments, offering supplementary or clarifying information.

As Starkey (Reference Starkey1990) explains, the primary aim of the prize court system was not to evaluate individuals but to determine the legality of maritime captures. It was a procedure grounded in documentary evidence, where sailors’ statements – particularly those about origin, employer, cargo, and voyage details – had to be plausible and verifiable and were assessed in conjunction with official paperwork. Declaring a sovereign was a procedural obligation taken seriously by the courts, yet we find no evidence that such declarations had direct personal consequences for the individuals involved. Few tangible benefits or penalties were tied to naming one side over another, as judgments primarily hinged on the national character of the vessel and the legal status of the voyage (Starkey Reference Starkey1990).

This relative absence of personal stakes reinforces the reliability of the allegiance statements. With little to gain or lose from naming one sovereign over another, sailors had limited incentive to dissemble. Moreover, much of the surrounding information – such as birthplace or employment history – was verifiable through muster rolls, shipping registers, and correspondence with foreign authorities. These records enabled courts to identify inconsistencies and expose false claims. In this context, while allegiance itself may not have been directly verifiable, its expression was embedded in a system that rewarded coherence and penalized contradiction. It is unlikely, therefore, that these men would have consistently fabricated or manipulated their declarations in the hope of leniency.

While we have good reason to trust the factual accuracy of the data, it is the variation within the data that provides insight into the lived dynamics of allegiance. Responses diverge even among men from the same region or occupational background. The division is nearly even: 52 percent of the individuals in our dataset reported a shift in loyalty toward the Dutch Republic, while 48 percent remained aligned with the sovereign of their birthplace. Remarkably, the geographic distribution across both groups is strikingly similar, suggesting that regional origin alone does not explain variation in loyalty.

This is shown in Figure 2, which presents two maps that plot the geographic distribution of birthplaces for the individuals in our dataset – one for those who identified with the Dutch Republic and one for those who remained loyal to their original sovereign. Despite the nearly even split between these groups, the spatial patterns are strikingly similar. This suggests that the region of origin alone did not systematically shape allegiance outcomes.

Figure 2. Places of birth of individuals in the dataset

Note: The left panel (green dots) shows those staying loyal to their sovereign of birth; the right panel (red dots) shows individuals who switched allegiance to the Netherlands

This internal heterogeneity is central to our analysis. Rather than a dataset shaped by uniform incentives or coercion, the PPD reveals diverse expressions of affiliation, filtered through individual life courses and local contexts. The remainder of this article investigates the factors that informed these declarations – ranging from residence duration and occupational status to age, marital ties, and cultural origin – and situates them within the broader historical context of sovereignty and identity in the early modern maritime world.

Patterns of allegiance: Determinants of host-country identification

What factors shaped the decision of foreign-born seamen residing in the Dutch Republic to identify with their host country? While our data do not support causal claims, we can examine correlations between personal and institutional characteristics and self-declared allegiance, providing insight into the dynamics of host-country identification in the late eighteenth century. In this article, as discussed earlier, we interpret declared allegiance during interrogation not necessarily as a direct expression of inner sentiment, but rather as a public articulation of civic affiliation under legal and institutional scrutiny.

To frame our expectations, we draw on modern political sociology and early modern historiography. Reeskens and Wright (Reference Reeskens and Wright2014) argue that national identification depends more on social embeddedness than on length of residence alone. While their study contends that social embeddedness more reliably predicts national attachment than time alone, they note that duration of residence remains a widely used benchmark in classical assimilation theory (Alba and Nee Reference Alba and Nee2003; Gordon Reference Gordon1964). We include it here to assess whether time in the host society independently affects civic identification in the early modern context. Meanwhile, studies by Prak (Reference Prak1997, Reference Prak2022) emphasize the role of institutional affiliation through local citizenship (burgher or poorterschap) in shaping early modern civic identity. Finally, occupational rank may signal deeper institutional embeddedness and public responsibility, factors that Reeskens and Wright (Reference Reeskens and Wright2014) associate with stronger civic attachment. In the early modern context, ship captains held formal authority, interacted more frequently with institutions, and were often citizens of the cities they sailed from (Bruijn Reference Bruijn2011, Reference Bruijn2016). We therefore hypothesize that higher occupational rank, especially as captain, increases the likelihood of Dutch identification. Additionally, the Prize Paper testimonies themselves suggest that marriage may have served as a mechanism of social integration: as we saw with Harman Emling, who explicitly connected his marital status and his wife’s residence in Amsterdam to his shift in allegiance to the States General, suggesting that marriage created local ties that influenced civic identification.

Based on these insights, we formulate four hypotheses, which we test using four regression models, moving from contextual (Model 1) to personal (Model 2) variables, combining both (Model 3), and finally introducing interaction terms (Model 4) to explore how personal status moderated contextual effects.

Hypothesis 1: Residence duration: While social embeddedness is often more important than time alone (Reeskens and Wright Reference Reeskens and Wright2014), we test whether longer residence is nonetheless associated with greater host-country identification.

Hypothesis 2: Citizenship status: Holding Dutch city citizenship increases the likelihood of Dutch identification, while citizenship elsewhere decreases it.

Hypothesis 3: Occupational rank: Higher occupational rank, especially serving as a captain, increases the likelihood of Dutch identification, as rank may reflect greater integration into institutional frameworks and civic structures.

Hypothesis 4: Marital status: Marriage increases the likelihood of Dutch identification, as it creates local social ties that anchor individuals in the host community.

Beyond these core hypotheses, we include several additional variables to control for demographic and contextual factors that may influence allegiance patterns. Age may affect identification through different mechanisms: socialization theory suggests that social attitudes are formed early in life and remain largely stable thereafter, with younger individuals typically appearing less patriotic than older ones (Reeskens and Wright Reference Reeskens and Wright2014). Literacy is measured in our dataset as the ability to sign one’s name, serving as a proxy for education (Van Lotum and Van Zanden Reference van Lottum and van Zanden2014). Following Reeskens and Wright (Reference Reeskens and Wright2014), education may affect identification by expanding individuals’ reflective horizons and making them more critical toward authority, potentially influencing patterns of allegiance. We also control for period effects by distinguishing captures before and after 1795, when the Dutch Republic collapsed and was replaced by the Batavian Republic. This political transformation fundamentally altered the institutional landscape and may have affected how migrants, particularly those in positions of authority, perceived and articulated allegiance to Dutch institutions.

Our analysis draws on 288 individuals from the Prize Papers Dataset, all born outside the Dutch Republic but residing there at the time of capture. Some variables traditionally associated with integration, such as language acquisition or religion, were not available in the Prize Papers Dataset and could not be included. The reduction from 288 to 264 cases reflects listwise deletion of observations with missing values on one or more variables. The dependent variable is their stated allegiance during Admiralty court interrogations, coded as either continued loyalty to their polity of origin or a shift in identification to the Dutch Republic. We use binary logistic regression to assess the relationship between allegiance and a set of independent variables. In this model, the probability (p) of identifying with the Dutch Republic is compared to the probability of not doing so (1-p), and coefficients represent the natural log of the odds ratio. When exponentiated, these coefficients yield odds ratios, which indicate the change in likelihood of Dutch identification resulting from a one-unit change in the independent variable (Menard Reference Menard1995). We present the full set of logistic regression results (Table 1).

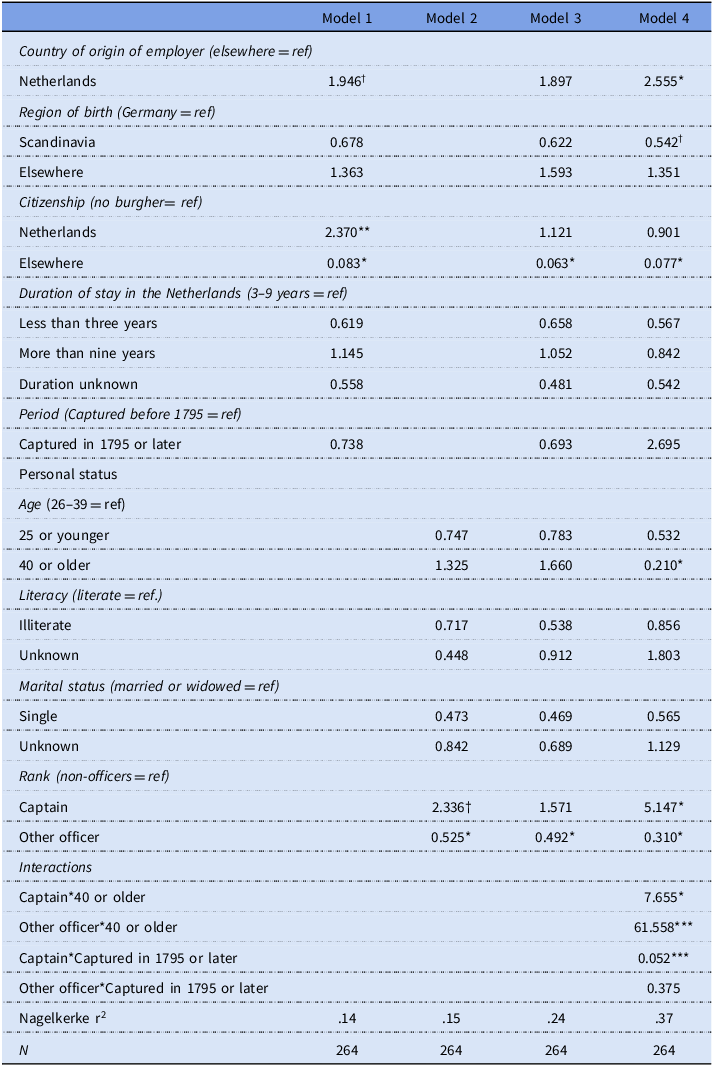

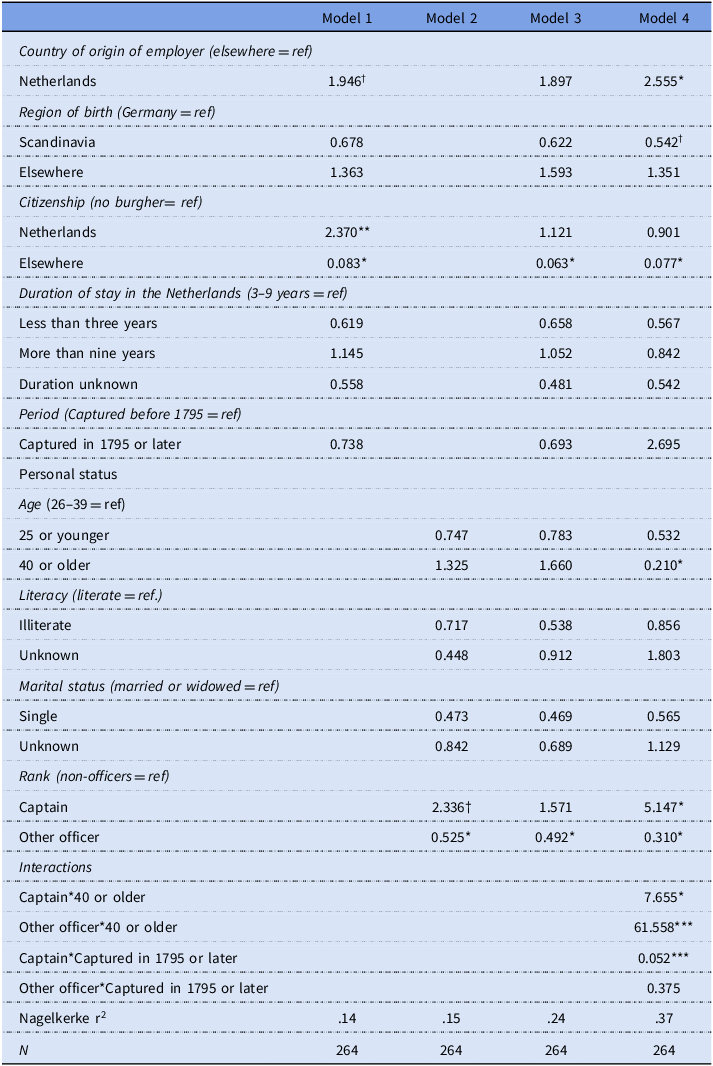

Table 1. Logistic regression results: determinants of host-country identification, 1776–1801, odds ratios

Note: † p < .10, *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001. Coefficients represent odds ratios from binary logistic regression models. Values greater than 1.0 indicate increased likelihood of Dutch identification; values less than 1.0 indicate decreased likelihood.

Hypothesis 1: Residence duration: The length of time spent in the Dutch Republic shows no statistically significant relationship with allegiance. Individuals residing for over nine years were only marginally more likely to identify with the Republic than those with shorter residence, and these differences are not significant across any model. Hypothesis 1 is not supported.

Hypothesis 2: Citizenship status: In the Dutch Republic, “citizenship” (or poorterschap) typically referred to formal burgher status granted by a city, often requiring payment, a period of residence, and sometimes guild membership or militia service. As we referred to earlier, this form of civic membership was highly localized and functioned less as a national identity than as a bundle of legal privileges, responsibilities, and access to institutions (Prak Reference Prak1997, Reference Prak2022). Despite its local character, Dutch city citizenship is the most robust predictor of host-country identification in Model 1, more than doubling the odds of Dutch allegiance. Conversely, having (again: local) citizenship elsewhere reduces the odds of identifying with the Republic by over 90 percent. Although the Dutch citizenship effect weakens in Model 3 (when personal variables are included), the effect of non-Dutch citizenship remains strong and significant across models. Hypothesis 2 is strongly supported.

Hypothesis 3: Occupational rank. Captains are significantly more likely than ordinary seamen to identify with the Republic. This effect is strongest in Model 1 (odds ratio approximately 2.34) and becomes highly significant in Model 4 when interaction terms are introduced. In contrast, other officers are significantly less likely than non-officers to identify with the Dutch Republic. These results suggest that rank had a complex but meaningful relationship with allegiance. Hypothesis 3 is partially supported.

Hypothesis 4: Marital status. Contrary to expectations, marital status shows no significant relationship with Dutch identification in our models. While married individuals might be expected to have stronger local ties, the aggregate effect is not statistically detectable in our sample. This may reflect the complexity of how marital ties shaped civic identity in ways that our available variables cannot fully capture or suggest that the effect of marriage depends on factors not captured in our models, such as the nationality of spouses. Hypothesis 4 is not supported.

Control variables. As Table 1 shows, the demographic variables included as controls reveal some notable patterns, though most effects are not statistically significant. Age alone shows little effect on allegiance in the main models, though it becomes important when combined with occupational rank, as explored below. Literacy, similarly, shows no significant association with allegiance patterns. While literate individuals might be expected to engage more deeply with civic institutions, the effect appears modest in our maritime sample, where occupational rank and formal citizenship status seem to matter more than educational background. The period variable captures the institutional transformation of 1795, when the Dutch Republic was replaced by the Batavian Republic under French influence. While the main effect is not significant, this political shift had differential impacts across occupational groups, as discussed in the interaction analysis below.

Interaction effects and regional patterns. Beyond these main effects, Model 4 highlights how personal characteristics intersected with broader political shifts. Age shows an interesting interaction with occupational rank: while age alone has little effect on allegiance, older officers (particularly those over 40) are dramatically more likely to declare Dutch allegiance, with odds increasing by over sixty-fold. This may reflect how institutional embeddedness becomes more meaningful with both experience and authority. Conversely, captains captured after the regime change of 1795 were significantly less likely to identify with the Dutch Republic, perhaps reflecting uncertainty about institutional continuity among those whose authority depended on stable governance structures. This suggests that elite perceptions of civic allegiance were sensitive to political change, in line with Prak’s argument that civic membership was responsive to legitimacy and regime continuity. Finally, while earlier descriptive analysis suggested little variation by origin, the regression models reveal some distinctions. Scandinavians were somewhat less likely than Germans to identify with the Dutch Republic, while individuals from other regions were more inclined to do so. These effects, however, are not statistically significant.

Taken together, the results in Table 1 suggest that host-country identification in the eighteenth century was shaped less by geographic origin or duration of stay than by institutional integration and personal position. Legal status, age, and especially occupational role shaped how seamen articulated allegiance. This internal heterogeneity, also observed in the descriptive findings of the previous section, was not random but followed interpretable social and political patterns. The combination of regression analysis and archival data thus helps illuminate the layered and contingent nature of early modern civic identification. The final section reflects on what these findings reveal about national identity in the early modern world.

Conclusion: Allegiance before nationalism

When we first encountered captains Andreas Mulder and Mathys Andriesz, they appeared strikingly similar – both Danish-born, married, close in age, and long-time residents of Amsterdam. Yet their declarations of allegiance diverged: Mulder embraced his adopted homeland, while Andriesz remained loyal to Denmark. What, at first glance, seemed like a simple difference in personal choice is now more clearly understood as the product of a complex matrix of factors – biographical, institutional, and contextual – that shaped how early modern migrants articulated belonging.

This article has used these and other testimonies to explore a broader historical question: how did early modern migrants express affiliation to their host polity before the emergence of nationalism? We approached this question by testing four hypotheses drawn from political sociology and early modern historiography: that host-country identification would be associated with (1) longer residence in the Dutch Republic, (2) local citizenship, (3) occupational rank, and (4) marital status. While the results do not support all hypotheses equally, they reveal meaningful patterns. Most notably, Dutch city citizenship and higher occupational rank – especially among captains – were strongly associated with identifying with the Dutch Republic. These factors mattered because they reflect concrete forms of institutional embeddedness. Poorterschap (city citizenship) conferred access to guilds, markets, legal protection, and participation in civic institutions, anchoring individuals materially and symbolically in the host society. Higher occupational rank, particularly that of captains, often entailed greater institutional contact, responsibility, and public trust. Captains were not only more likely to be citizens themselves but also to be seen – and to see themselves – as representatives of the urban polity they served. By contrast, length of residence showed only a weak and statistically insignificant association. These findings support Reeskens and Wright’s (Reference Reeskens and Wright2014) emphasis on institutional embeddedness over duration and align with Prak’s (Reference Prak1997, Reference Prak2022) characterization of civic membership in the Dutch Republic as conditional, localized, and responsive to political structure.

At the same time, allegiance in the early modern world cannot be reduced to any single factor. Legal status, occupational authority, and the broader political regime all intersected in shaping how individuals positioned themselves. Captains were notably less likely to identify with the Republic after the 1795 regime shift, suggesting that political upheaval affected the allegiances of those whose authority depended on institutional continuity. This pattern is consistent with the idea that civic identity was sensitive to shifts in legitimacy and governance.

Rather than capturing nationalist sentiment, the Prize Paper interrogations reveal allegiance as a civic and institutional category – structured by legal status, occupational roles, and social ties. These declarations, made under legal scrutiny, reflect how affiliation was negotiated within a framework of state power and civic responsibility. They point to a mode of identification grounded not in affective nationalism but in practical, institutional, and relational considerations.

These insights contribute to reframing early modern identity not as a precursor to nationalism but as a distinctive historical formation shaped by pragmatic alignments, legal affiliations, and institutional embeddedness. By complementing statistical patterns with individual life trajectories, we gain a fuller understanding of how allegiance functioned as a lived category – responsive to opportunity, shaped by structural contexts, and navigated through personal and professional choices. They also speak to contemporary debates on civic integration, showing that identification with a host polity has long depended on both institutional opportunities and individual agency. Most importantly, this analysis returns attention to the migrants themselves – Jacobs, Pranger, Emling, Mulder, Andriesz, and others – whose voices, preserved in the archive, continue to challenge our categories.

The quantitative results can be deepened through targeted biographical research, which offers a vital complement to statistical analysis by illuminating the lived experiences and relational dynamics behind observed patterns (Van Lottum and Petram Reference Van Lottum, Petram and Brauner2025). Although regression models reveal correlations between civic status, rank, and allegiance, biographical inquiry can uncover the mechanisms through which these affiliations were formed and expressed. This dual approach allows us to better understand how institutional pathways intersected with personal histories in shaping expressions of host-country identification.

Archival work in Amsterdam not only has the opportunity to corroborate the information in the Prize Papers but also enriches it with personal detail. It reveals that both Mulder and Andriesz settled and married in Amsterdam, yet only Mulder – who identified with the Dutch Republic – wed a Dutchwoman.Footnote 1 While our regression models did not detect a significant aggregate effect of marital status on allegiance, the biographical evidence suggests that marriage – particularly to Dutch partners – may have reinforced civic identification in individual cases. Future research incorporating data on spousal nationality could better illuminate this relationship, as marriage to local partners represents a form of social embeddedness that our institutional variables may not fully capture. Though anecdotal and beyond the scope of our models, such evidence highlights how private relationships may have reinforced civic affiliation. It also suggests fertile directions for future research at the intersection of personal networks and public belonging in early modern Europe – where the articulation of allegiance was shaped not only by legal or institutional factors but also by the intimate ties that anchored migrants in their adopted communities.