Introduction

A key challenge in a historical supervision analysis is defining the relevant terms. The objectives of both financial regulation and supervision have evolved. Today, supervision refers to measures aimed at improving the safety and soundness of the banking sector. In the past, however, banking supervision in many countries had a broader mandate and endeavored to ensure banks’ compliance with various measures related to economic policy. This research aims to determine which aspect of banking supervision sought to maintain the stability of the banking sector, which is the primary goal of current supervision. This article shows the changing interests that shaped supervision and its evolution in twentieth-century Spain. Pressures from the banking sector, political factors, and economic considerations drove the changes in supervision, in a process similar to that in other European countries in the region.

The role of supervision has evolved significantly over time and varied across countries.Footnote 1 The historical and institutional context of a country shapes its banking regulation and supervision, as do the unique characteristics of its financial system. Early supervisory efforts were quite rudimentary, focused primarily on establishing entry controls and gathering basic statistical data. As financial systems developed, supervision systems became more sophisticated. Nevertheless, financial stability has never been the sole objective of supervision, either in the early stages or in the more complex frameworks. Government interests, central banks, and pressure groups—especially within the banking sector—played pivotal roles in shaping banking regulation and supervision. In many cases, the outcome resulted from the interactions between these agents and their capacity to exert influence.Footnote 2 As GrossmanFootnote 3 notes, both economic and political motives have historically driven regulation and supervision, and it is difficult to disentangle the main motivations behind a financial reform. We find an example of this in the US case, where banking supervision evolved through a mix of decisions by different actors rather than from a single plan. Progress was not linear but emerged from the interaction between public and private agents seeking to balance their interests and adapt to a changing financial environment.Footnote 4

During periods of greater interventionism—such as the one examined here, from the end of World War II until the mid-1970s—supervision in many countries went no further than ensuring compliance with regulations (financial compliance). The aim was not always to guarantee the proper functioning of banking institutions, but rather to serve the interests of the banks (for example, to control competition) or the state (using ratios to affect the distribution of credit or public debt). This interventionist nature of supervision is evident in France. The Banking Act of 1941, triggered by the German occupation, included prudential regulation measures, such as minimum capital requirements for banks, the public disclosure of bank accounts, and the requirement for banks to register. The 1945 Banking Act nationalized the major deposit banksFootnote 5 and established a “control network” to control credit policy and align public economic policy with private interests.Footnote 6 In Italy, interventionism began earlier, during the Fascist period, with the 1926 and 1936 Banking Laws,Footnote 7 which granted regulatory and supervisory powers to the Treasury.Footnote 8 However, the Bank of Italy exercised its responsibility for supervision through the Inspectorate for the Safeguarding of Savings and Credit Activity. In 1947, the Inspectorate was dissolved, and the Bank of Italy directly assumed all supervisory powers. Despite this transfer, the Bank remained subject to oversight by the Minister of the Treasury for banking control and credit policy matters.Footnote 9 In Germany, the first steps towards banking supervision were linked to the political control the Nazi regime exerted over the banking sector and were aligned with the government’s economic policies. It was not until after World War II, with the 1961 Banking Law, that supervision explicitly sought to preserve financial sector stability.Footnote 10 Unlike other European countries, the UK did not have formal supervision until 1979, opting instead for an informal model based on moral suasion.Footnote 11

The literature on Spanish banking supervision is relatively recent, and studies on the Spanish banking sector only partially address supervisory issues.Footnote 12 In Spain, the first steps towards formalizing banking supervision were the enactment of the 1921 Banking Law and subsequent reforms in 1931, which made the Bank of Spain the supervisory authority.Footnote 13 Following the Civil War (1936–1939), however, Franco took more control over the Bank of Spain and the rest of the financial sector. Regulatory measures were not very different from those in other countries. Nevertheless, the implications of the distinct political context in Spain, a dictatorship, make it a particularly interesting case to examine. This paper builds on Pons’s analysisFootnote 14 of Spanish financial regulation under Franco, aligning closely with the framework by Calomiris and Haber.Footnote 15 The centralized autocratic system in Spain gave rise to a “game of bank bargains,” creating a regulatory framework that assigned banks and savings institutions a central role in Franco’s development strategy, supporting industrialization and providing the state with cheap financing. In return, banks benefited from low risk, greater market power (due to entry restrictions and limited competition), and influence over regulation and supervision. Over the four decades of the Franco dictatorship, banking regulation and supervision evolved through a shifting government-banking industry relationship.

Our evidence shows that from the 1940s until the mid-1950s, banking supervision was virtually nonexistent, and regulatory capture seems to have prevailed. In the late 1950s, notable changes in economic policy and banking sector performance impacted banking supervision and its key players. Consequently, banking control and inspections increased, especially after the 1962 Banking Law. Despite this progress, the banking sector still exerted significant influence, indicating a degree of regulatory capture. The 1962 Banking Law, stemming from the Franco regime’s increased political and economic openness after the 1959 Stabilization Plan,Footnote 16 included the nationalization of the Bank of Spain. Decree Law 18/1962 restored supervisory functions to the central bank, leading to the gradual formalization of banking supervision over the following years. Notwithstanding these efforts, the liberalization and increasing competition in a context characterized by insufficient supervisory mechanisms triggered a major banking crisis after 1977.

This paper aims to analyze the evolution of banking supervision during the Franco regime (1940–1975). It seeks to answer the following questions: What was the status of banking supervision after the war and during the first two decades of the Franco regime (the 1940s and 1950s)? How big were the changes in supervision in subsequent years, especially during the 1960s and 1970s? What factors explain the differences in banking supervision during the two periods? Did the degree of supervision in the banking sector depend on its oligopolistic nature? To what extent did pressure from the government and the banking sector influence the Bank of Spain’s supervisory action? To this end, we conduct an analysis of banking inspection regulations during the Franco regime, as well as examining the supervisory action—drawing from the resources available in the Historical Archive of the Bank of Spain (AHBE)Footnote 17—and the economic policy framework that explains these developments.

Spanish Banking Supervision After the Civil War and During the First Two Decades of the Franco Regime (1940–1962): Government Capture?

During a post-Civil War recession with low growth and high inflation, Spain had a relatively small, bank-based financial sector. It only grew significantly in the 1950s and 1960s due to improved economic activity.Footnote 18 Previous studies have used various indicators to assess the oligopolistic nature of the Spanish banking sector under Franco, including the concentration level in the banking industry, the connections between banks and major industrial firms,Footnote 19 agreements to fix interest rates and limit competition,Footnote 20 and high profitability compared to other banking sectors.Footnote 21

A combined analysis of all these indicators provides several key insights. PueyoFootnote 22 demonstrates an increase in concentration from the end of the Civil War until 1953. However, from 1954 onward, both banking concentration and the concentration of banking groups began to decline. In this period, banks had a significant presence on the boards of many Spanish firms, and the presence of interlocking directorates indicates monopolistic tendencies.Footnote 23 For instance, by 1967, the six largest banks (Español de Crédito, Hispano Americano, Central, Bilbao, Vizcaya, Urquijo) held positions on the boards of directors of 955 companies. While this number was relatively small, representing only 4.6% of all Spanish firms, their capital accounted for approximately 70.6% of the total capital of Spanish firms.Footnote 24 Finally, there were occasional banking agreements to limit deposit interest rate competition. As García RuizFootnote 25 indicates, the banks signed agreements in 1941, 1949, and 1952 to set interest rates on deposits below the official maximum. All of these were private agreements, except the 1952 agreement, which involved the Ministry of Finance. In 1941, the corporatist organization representing banking interests was the Comité Central de la Banca Española, which later changed its name to Consejo Superior Bancario (CSB) in 1946. The CSB also acted as a liaison between banks and authorities. Such interest rate agreements were not unique to the Spanish banking sector.Footnote 26 Due to financial instability in the first third of the twentieth century, some other European banking sectors also used agreements to mitigate the adverse consequences of competition and promote stability.

In the CSB Act of October 27, 1953,Footnote 27 the president highlighted numerous complaints about violations of the agreements. To evaluate the effectiveness of banking controls, PonsFootnote 28 estimates the cost of deposits for the Big Five Banks and compares it with the legal maximum set by the authorities from 1940 to 1975. The results indicate that between 1940 and 1950, banks paid a deposit interest rate very close to the legal maximum. However, from the early 1950s onward, financial costs exceeded the legal maximum. Garcia RuizFootnote 29 corroborates this finding with evidence on Banco Hispano Americano, noting that the bank violated the interest rate agreement in 1949 and pointing out a significant increase in deposit interest rates above the agreed rates from 1952 onward.

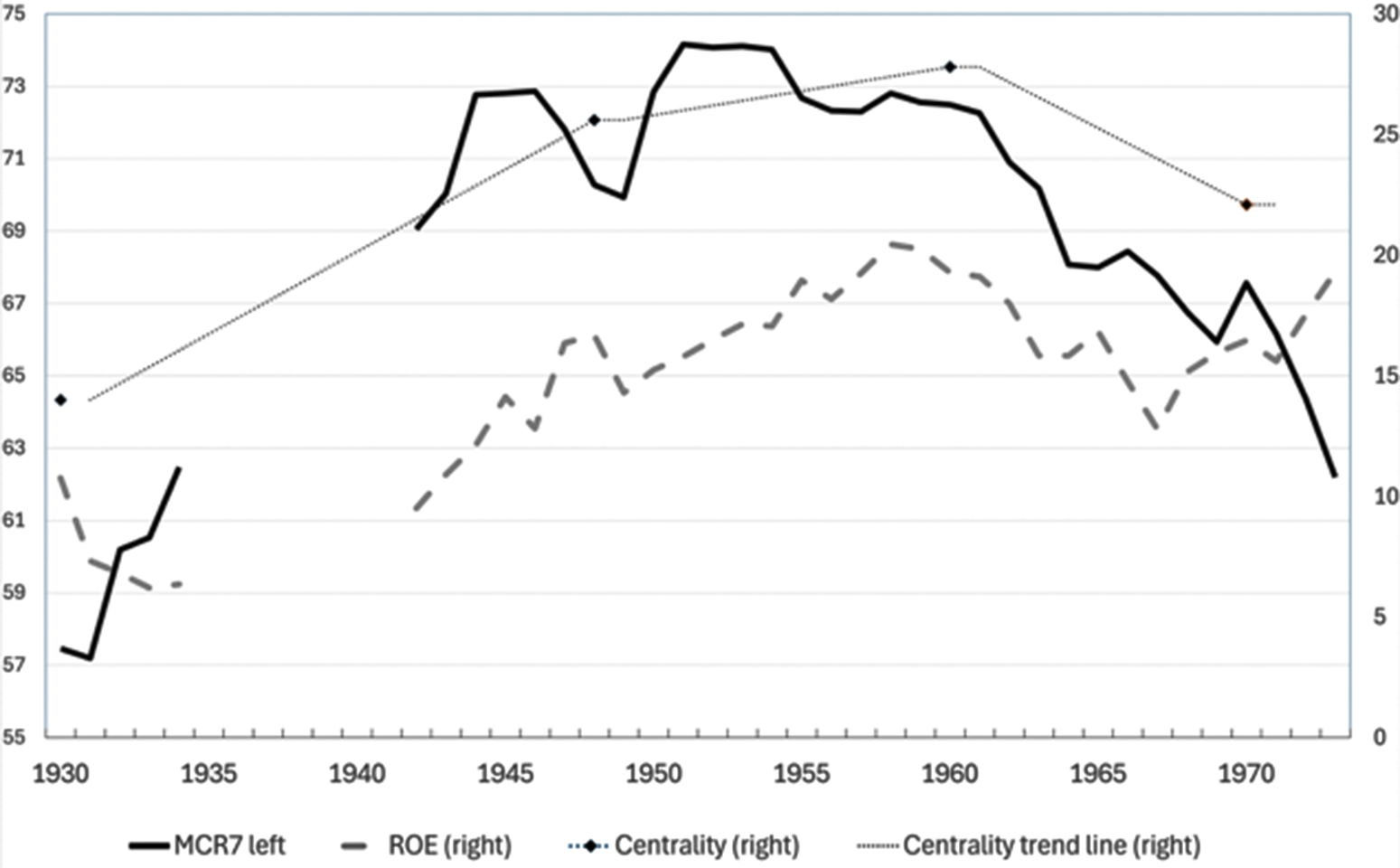

Figure 1 shows the lack of competition in the Spanish banking sector. The deposit concentration ratio of the top seven banks (MCR7) shows that market power increased during the 1940s, stabilized in the 1950s—albeit with a slight downward trend—and further decreased in the 1960s. Simultaneously, the level of interconnection between the banking sector and other sectors through shared board members, which we measure using the degree of centrality indicator, exhibited a similar trend. Banking profitability mirrors this pattern, rising steadily from the end of the Civil War until the late 1940s. The shift in the trend of all three indicators around the late 1950s suggests that they may be correlated. It is therefore likely that the close relationships between companies contributed to the concentration of the banking sector, which, in turn, may have driven its high profitability.

Figure 1. Comparative evolution of concentration (MCR7), financial profitability (ROE), and the degree of centrality in banking, 1930–1973.

Note: Market concentration (MCR7) is the percentage of deposits held by the seven largest banks; Financial profitability (ROE) is the average profitability or return on equity of the seven largest banks; Degree of centrality (DC) shows the percentage of connections with other sectors. The higher the number, the more interconnected. We have included a two-year moving average trendline.

Source: MCR7 from Pueyo, 2003; ROE from Pueyo, 2006; DC from Rubio-Mondéjar and Garrués-Irurzun, 2016.

To sum up, while all these results confirm the lack of competition during the 1940s, they also reveal a tension between collusion and competition from the early 1950s on. They also show that, at certain times, price competition (albeit imperfect) prevailed over restrictive agreements. The 1962 Banking Law, which facilitated branch network expansion, fueled competition in the 1960s and 1970s. However, there was little progress in financial liberalization in other areas. Furthermore, our results confirm a lack of homogeneity in banking sector operations from 1939 to 1975, with phases of virtually no competition and others where banks attempted to compete in certain areas, such as attracting deposits. A key question in this context is how banking supervision operated during this period and whether or not the aforementioned changes affected its evolution. Did banks capture the supervisory process, meaning supervision was not firmly aimed at guaranteeing banking stability? Can we observe changes in banking supervision in this period?

Banking Supervision After the Civil War: The Rules

After the Civil War, the 1942 and 1946 Banking Laws established the main rules in terms of banking performance. Among other measures, they introduced control over entry into the sector (banking status quo) and expansion through branches; set a maximum interest rate payable on current accounts, deposits, and other similar operations; set minimum interest rates and commissions on active operations; established time limits on assets and liabilities, with a 90-day limit on the provision of credit; introduced rules to control bank dividends; and defined minimum capital requirements and the relationship between own resources, realizable assets, and enforceable obligations. Most of these measures did not differ from those in other countries during that period. As VivesFootnote 30 asserts concerning banking regulation in developed countries: “From the 1940s to the 1970s, competition between financial institutions was severely limited by the regulation of rates, activities, and investments, the separation between commercial banking, insurance and investment banks…, restrictions on the activity of saving banks, and geographical segregation… Deposit insurance was established, and the central banker acted as a lender of last resort.” These measures, which resulted from negotiations between public and private actors, reduced competition and thus preserved financial stability.Footnote 31 Banking regulation in Spain, therefore, followed a similar pattern to that in other European countries, with one key exception: the absence of a deposit insurance system. The Bank of Spain introduced this system in 1977, in response to the banking crisis of that decade. Before that, if a bank faced liquidity or solvency problems—which was rare, at least until the second half of the 1960s—the solution typically involved support from larger banks, which would often absorb the troubled entities, or limited rediscounting by the Bank of Spain.

Regarding supervision, the Bank of Spain lost its supervisory authority originally granted under the 1921 Banking Law, representing a clear setback.Footnote 32 This shift occurred before the end of the Civil War, when the Franco Law of August 27, 1938 granted the Ministry of Finance the authority to determine credit policies and carry out sporadic bank inspections, thus transferring responsibility for banking supervision from the Bank of Spain to the Ministry of Finance. The 1946 Banking Law ratified this, and it established two crucial institutions for banking supervision: it reinstated the CSB created by the 1921 Banking Law, which represented the banking sector interests and acted as a lobby, and it launched the Dirección General de Banca y Bolsa e Inversiones (DGBB).

This new CSB, which the government closely supervised, continued as the corporatist banking institution responsible for collecting the banking statistics and ensuring compliance with regulations on interest rates, bank branches, and other banking operations. It was similar to the Comité Permanent d’Organisation des Banques in France, created in the 1941 Banking Act.Footnote 33 According to the 1946 law, the CSB’s main function was to interpret and monitor compliance with the Ministry of Finance regulations on bank service fees, reporting any violations or irregularities to the Ministry. During Francoism, the CSB continued as the banking sector’s corporative body, while also serving as a channel for government interests.

The DGBB, created with the Decree of 2 March 1938 and ratified in the Banking Law of 1946, was under the authority of the Ministry of Finance. The DGBB had the power to open an occasional inspection—either through its own personnel or, in some cases, through the Bank of Spain—and to impose sanctions. Regarding sanctions, the 1946 Law primarily penalized noncompliance with regulations on dividend payment, bank branch opening, provisions for reserve funds, transparency and accuracy of balance sheets and income statements, and interest rates. Sanctions ranged from warnings and private reprimands to reprimands of the entire banking sector, as well as fines (either a fixed amount or proportional to the infraction, if quantifiable). In cases of repeated violations, the law also allowed for the suspension of bank executives. For the most serious cases, sanctions could include exclusion from the Registry of Operating Banks in Spain and the dissolution of the sanctioned entity. In the case of more severe penalties, the final decision lay with the Minister of Finance, based on a proposal from the DGBB and a prior report from the CSB. Finally, the 1946 Banking Law obliged banks and bankers to remit the balances and the profit and loss accounts to the DGBB, the CSB, and the Bank of Spain. Throughout most of the period of autarky, supervision was mainly off-site and limited to the submission of information. We found no evidence of interactions or correspondence between supervisors and supervised banks on this matter.

Banking Supervision After the Civil War: The Inspections

The key question is how the new regulatory framework, and specifically the shift from the Bank of Spain to the Ministry of Finance, influenced banking supervision and inspections. Firstly, as mentioned, there was a change in the supervisory authority, with the Ministry of Finance taking over from the Bank of Spain concerning oversight. Prior to the Civil War, Bank of Spain personnel carried out inspections, but after the war, DGGB technicians, usually chartered accountants, took on responsibility for inspections under the authority of the Ministry of Finance. This change reflects how Franco’s regime restructured financial policy oversight, reducing the central bank’s autonomy in favor of new institutions directly dependent on the Ministry of Finance. Additionally, the Franco government established a new body under the Ministry of Industry and Commerce to control foreign exchange transactions and international trade: the Instituto Español de Moneda Extranjera (IEME, or Spanish Foreign Currency Institute), created in 1939 and operational until 1973. By separating exchange rate policy from monetary policy, the regime made exchange controls a key trade policy instrument. This was particularly important, as one of the regime’s main challenges—arising from its autarkic policies—was a chronic shortage of foreign currency.Footnote 34 As a result, the IEME participated in the banking inspections, specifically in all issues related to foreign exchange.

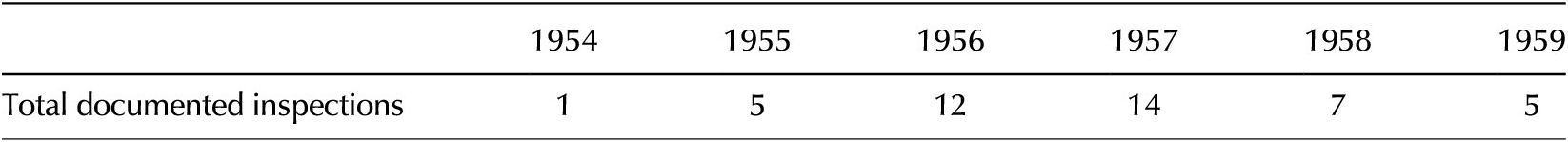

Secondly, the number of inspections dropped in the postwar years. We have evidence of very few inspections from 1925 to 1936: six in total.Footnote 35 However, there is no evidence of any inspections at all from then until the late 1940s.Footnote 36 The situation changed in the mid-1950s, when the number of inspections increased, reaching a peak in 1956 and 1957 (12 and 14 inspections, respectively) (Table 1). In 1957, the peak year for inspections during the 1950s, DGGB technicians inspected more than 12% of all banks.Footnote 37

Table 1. Banking inspections, 1954–1959

Source: AHBE, Banca Privada, C.929, C.930, C.931, C.932, C.956, C.957, C.958, C.970; AHBE, Inspección, C.126; AHBE, CSB, C.298/01.

Thirdly, regarding the objectives of supervision and inspection, the primary aim of these activities was not to ensure the banking system’s stability, either before or after the war. Before the war, most inspections aimed to monitor foreign exchange operations and tariff violations. A notable exception was the inspection of Banco Central, one of the largest Spanish banks. Beginning just days before the outbreak of the war, the primary aim of this inspection was to assess the solvency of the institution due to credit risk,Footnote 38 but the war prevented its completion. Furthermore, the potential implications of this inspection were on a different scale to those of smaller institutions conducted during the late 1940s and the 1950s.

An important question is whether the rise in inspections during the 1950s reflects efforts to ensure banking stability or whether other factors drove the increase. Our findings reveal that it was not government efforts to ensure stability by reducing risky banking operations that drove the increase in supervision from the mid-1950s. Instead, it arose in response to pressure from banks themselves, stemming from their noncompliance with the agreed-upon rules designed to limit competition. Nonetheless, maintaining low interest rates also benefited the Franco government, allowing it to secure cheap financing by issuing public debt at similarly low rates.Footnote 39 As mentioned, after the war, banks adopted several agreements to limit competition through interest rates. However, not all the banks upheld these agreements, especially the one from 1952. In the minutes of the CSB session of October 27, 1953, the president indicated that he had received numerous complaints about violations of the agreements. In response, he announced the possibility of conducting “inspection visits as lengthy, firm, and thorough as deemed necessary.”Footnote 40 This coincides with the evidence obtained by PonsFootnote 41 and García RuizFootnote 42 regarding violations of the deposit interest rate agreements, as previously noted. In its minutes, the CSB highlighted concerns about the increasing competition among banks and between banks and savings banks, as the latter offered higher deposit interest rates than those set out in the banking agreements.Footnote 43

However, when analyzing the banking inspections carried out from the mid-1950s on, we cannot conclude that they focused solely on compliance with deposit interest rate limits and other legal regulations. While these issues were crucial to the Ministry accountants’ responsibilities, inspectors showed a growing interest in risk concentration. For example, the chartered accountant who inspected the Banco de Madrid in 1956 noted, “Both loans in the form of financial bill discounts and those with personal guarantees have a small number of clients as holders or debtors, who alone represent approximately 65 percent and 80 percent of the total cash balance of each group.”Footnote 44 In the same vein, the report on the inspection of the Banco Comercial de Menorca in 1958 indicated: “It is abnormal for a bank to have 4/5 (four fifths) of its banking assets committed to loans to a group of companies, whether or not they are related to it, but even more abnormal is the fact that these debtor companies belong to the majority group of the bank itself, which does not maintain an adequate distribution of risks.”Footnote 45

We can thus affirm that the accountants in charge of inspections, aware of the serious risk concentration problems of many Spanish banks, diligently carried out their inspections, concerned not only with regulatory compliance and competition control but also with issues affecting the solvency of the institutions. The main problem was that the actions of higher authorities, specifically the CSB, undermined this supervisory work. As mentioned, the 1946 Banking Law stipulated the need to consult the CSB about the sanctions imposed on banks. When the CSB received the inspection reports, it consistently recommended limiting the sanctions; as such, they were often very lenient, reduced to mere warnings or recommendations. In only a few cases, the CBS communicated the reprimands to the rest of the banking sector, and it rarely called for fines. In this regard, it is evident that the CSB functioned as a corporatist banking association. Although the leader of the CSB was not a banker, the representation of the banking sector was substantial. The CSB consisted of 16 members, including 13 board members, and the majority of the CSB’s board members represented private banks. This CSB’s attitude, as illustrated by the case of the Banco Comercial de Menorca, resulted in ineffective banking supervision, which contributed to an increasingly high-risk concentration in the banking sector.Footnote 46

Despite the relatively low number of inspections and the lax structure of sanctions, the banking sector remained stable during this period, with relatively few bank failures. Several factors explain this “positive” result. Firstly, the Bank of Spain intervened and supported banks in distress. Secondly, between 1941 and 1970, there were 109 mergers, with most occurring before 1960 and mainly involving local and family-owned banks.Footnote 47 Many of the merged banks struggled financially, making them attractive targets for national banks. In a regulatory environment that restricted geographical expansion through branch networks, acquisitions allowed larger banks to expand their market presence. Finally, a certain degree of self-regulation within the banking sector may have contributed to this stability. In this sense, the lack of competition was a better determinant of stability than supervision.

The government introduced very few stability measures in this period. While the 1946 Banking Law granted the Ministry of Finance the authority to require banks to deposit up to 20% of their total deposit liabilities in cash or unpledged securities with the Bank of Spain, the government never enforced this mandate. The banking sector severely criticized this legal measure,Footnote 48 but the government decided to maintain the power, despite never exercising it. Instead, the Bank of Spain’s cash reserves resulted from convention, self-regulation, operational convenience, or profit-maximizing strategies. Concerning the optimal level of loans banks should make, the Bank of Spain only issued “recommendations” rather than stipulating legally required levels.

Although we have obtained evidence that banks “captured” the regulatory and supervisory activities to some extent, regulation and supervision also included rules that did not favor banks but instead supported Franco’s economic program: For example, the limit on dividends and measures aimed at ensuring the cheap financing of the budget deficit and providing cheap investment funds for privileged sectors.Footnote 49 However, this last measure had a positive impact on banking stability. As Comin and CuevasFootnote 50 demonstrate, during the 1940s and until 1957, Spanish banks maintained an average of 20% of their assets in public debt, which could be pledged at the Bank of Spain. Although the growth of public debt on banks’ balance sheets and the increasing volume of credit the Bank of Spain extended to the public sectorFootnote 51 fueled inflation, it also protected banks from potential solvency and liquidity problems. In fact, during the 1940s and 1950s, banks facing temporary liquidity problems pledged a significant portion of the public debt at the Bank of Spain. During these two decades, the government relied solely on moral suasion to encourage banks to invest in public debt. Banks, in turn, chose to invest in public debt due to the low demand for credit and the high liquidity of these investments. Public debt investment, therefore, provided stability to the banking sector while simultaneously allowing the Franco state to secure financing below market prices for its industrialization project.

The Changes During the 1960s and Early 1970s

The 1962 Banking Law and Its Impact on Banking Supervision

The 1962 Banking Law aimed to address some of the major shortcomings in the Spanish financial system. According to the preamble to the law, it sought to transform the Bank of Spain into a “true” central bank, facilitate the financing of investments by promoting banking specialization, and encourage greater financial liberalization. One of its key provisions was the nationalization of the Bank of Spain, although this did not guarantee its autonomy; in fact, the Bank remained completely subordinated to the government’s interests. However, as noted below, nationalization was crucial in terms of supervision. The law also relaxed entry barriers, although these restrictions remained in place for foreign banks. Additionally, the law sought to encourage banking specialization by creating industrial and business banking. This led to the number of banks increasing from 109 in 1960 to 126 in 1965, although most new banks were small industrial banks linked to large existing commercial banks. Even so, the operational effects of progressive entry liberalization were clear: banking assets multiplied by fifteen between 1960 and 1975, particularly in credit investments. Nevertheless, there were numerous contradictions in the legislative measures ushered in by the 1962 Banking Law. Despite the “liberalization” spirit of the law, it increased state interventionism in several areas.

Liberalization was evident in certain aspects, such as relaxing restrictions on branching. Between 1964 and 1974, the government implemented its Branch Expansion Plans, using criteria that combined the existing competition in each town (number of branches) with the equity and liabilities of each bank. This led to a significant increase in the total number of branches—from 2,697 in 1960 to 4,291 in 1970 and 7,218 in 1975. This growth resulted in a rise in the number of branches per 10,000 inhabitants, from a very low 0.87 in 1960 (substantially lower than Italy’s 1.88 in the same year) to 2.03 in 1975, not very far from the figure of 2.12 in Italy.Footnote 52 Branching expansion became one of the key drivers of increased competition. However, in other areas, the law heightened interventionism; for example, it maintained interest rate controls and introduced liquidity and public debt ratios. In fact, public debt still represented the major share of the banks’ securities portfolios. Although the new law did away with the issuance of pledgeable debt due to its inflationary effects, the connection between private banks and the public sector remained strong, which explains the significant expansion of “privileged” loans in the 1960s. Thus, between 1962 and 1974, government legislation compelled the banking sector to provide the financial boost for the Development Plans.Footnote 53 In exchange for financing the Development Plans, the banks obtained special discount lines for these operations at the Bank of Spain. Although the 1962 Banking Law introduced certain monetary instruments—such as a special deposit requirement, a liquidity ratio, or a cash ratio—that could help ensure bank solvency and provide tools for managing monetary policy, in most cases, the main aim of maintaining the interventionist apparatus was to finance the state. The policy of “investment ratios” and preferential interest rates to finance “privileged sectors” was a crucial part of the interventionist program, but it was not specifically aimed at ensuring stability. However, this approach was not significantly different from similar measures implemented in other European countries, such as France.Footnote 54

Various changes in supervision followed the 1962 Banking Law, prompted by the nationalization of the Bank of Spain, increased competition, and growing risks in the banking sector. The nationalization of the Bank of Spain restored supervisory responsibilities to the central bank after 40 years. To facilitate this transition, the Ministry of Finance established a Collaborating Office in 1962 to work alongside the Bank of Spain. In 1970, the Ministry eliminated this office.Footnote 55 The Bank placed greater importance on financial stability and banking risk management than the Ministry of Finance had,Footnote 56 but it failed to deliver the expected results, partly due to its lack of autonomy. In 1961, Joan Sard, Director of the Research Department of the Bank of Spain, presented a Memorandum as part of preparations for a banking reform under the 1959 Stabilization Plan, in which he highlighted banking stability and risk control. The Memorandum conveyed the views of the Bank of Spain and outlined three key aspects of banking control: assessing assets and liabilities, ensuring regulatory compliance, and overseeing management to maintain solvency. This included mitigating risks such as excessive lending and speculative investments.Footnote 57 While the final 1962 Banking Law ignored most of the Memorandum’s recommendations,Footnote 58 many postenactment measures aligned with its proposals. The transfer of supervisory authority to the Bank of Spain marked a shift away from banks’ capture of supervisory activities and regulations to limit competition, and towards a focus on banking stability and risk control after 1962.

The supervision in the hands of the Bank of Spain brought about significant changes compared to the previous decade. First of all, inspections became regular. Additionally, the framework allowed for extraordinary inspections when circumstances required. Secondly, the Bank of Spain established its own corps of banking inspectors. Thirdly, in response to increasing competition and the enforced specialization of banks after 1962, inspections placed greater emphasis on credit control, which we illustrate below with specific examples from inspection reports. Besides promoting inspections, the new law led to the establishment of the Risk Information Center (CIR) for banks in 1963, savings banks in 1968, and credit cooperatives in 1981. Italy’s central bank created a similar organization in 1962 (Centrale dei rischi), while in other countries, such as Germany or France, such centers began operating after the Great Depression of 1929. The CIR compiled credit statistics and notified the Bank of Spain about cases that posed exceptional risk or exceeded prudential credit policy limits. This institution became an essential tool for obtaining information in bank control and inspection tasks, specifically in off-site supervision. Furthermore, as we will see, inspections also became more focused on credit concentration. Fourthly, while the IEME continued to operate, the Bank of Spain assumed operational responsibilities in foreign exchange matters, which was reflected in inspections. In 1969, the Bank of Spain’s Inspection Service took over the duties of foreign exchange control, further consolidating its role in managing the country’s monetary and exchange rate policies. Fifthly, in 1964, after banks failed to comply with interest rate agreements,Footnote 59 the Ministry of Finance assumed the authority to set interest rates for both assets and liabilities. The Bank of Spain and the Credit Institute for Savings Banks took on the role of enforcing compliance. While interest rate control remained a key focus of inspections, it now served different purposes. From this point on, rather than controlling competition by limiting deposit interest rates, the main aim of interest rate control was to encourage investment; for this reason, the Bank of Spain set a maximum cap on lending rates rather than a minimum. Finally, there was also a significant change regarding sanctions, such that the Bank of Spain took over responsibility for proposing sanctions to the Minister of Finance.

A critical part of our analysis is to assess whether these changes led to improvements in banking supervision. Regarding on-site inspections, although most were primarily focused on verifying the accuracy of the balance sheets and compliance with other issues (for example, application of tariffs and other specific regulations), they now also included reviews of the consistency and accuracy of the data provided by the bank in earlier off-site supervision. Another important aspect was the Bank of Spain’s intention for periodic inspections to occur biennially, with the caveat that inspectors could conduct additional visits if they observed worrying deviations in the indicators or if certain actions threatened the institution’s stability. Finally, the Bank of Spain made efforts to ensure the impartiality of inspectors, leading to a recommendation for biennial rotation in their assignment to a specific bank.

However, despite these positive changes, banking supervision problems persisted. The most significant issue was the lack of personnel. In a meeting on 25 November 1966, the Board of Directors of the Bank of Spain acknowledged that the Bank faced not only legal constraints on its ability to carry out inspections but also a shortage of inspectors: “In the summer of 1962, the Bank of Spain had to hastily organize an inspectors corps not for its own services, which it already had, but for [commercial] banking, highlighting that department heads with university studies or similar could apply to join the service.”Footnote 60 The first competitive exams for Bank of Spain inspectors, held in 1964, were internalFootnote 61 and resulted in an initial staff of just ten inspectors. In addition, the directors of the Bank of Spain branches collaborated with the inspectors.Footnote 62 By the late 1960s, the inspection corps had grown to sixteen, but it was still insufficient for effective inspections. Initially, candidates needed a university degree and at least ten years as head of one of the Bank’s departments or offices.Footnote 63 Due to challenges in meeting these requirements, the Bank later removed the university degree prerequisite.

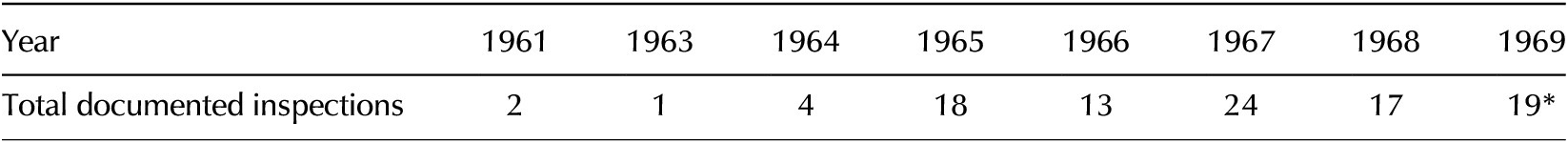

Despite the 1962 reform, there are very few documented inspections in the AHBE for the early 1960s. The reasons for this remain unclear but are likely related to the transfer of functions from the Ministry of Finance to the Bank of Spain. In contrast, we have more information from the mid-1960s, when the Bank of Spain inspected approximately 14% of the banks; specifically, in 1965, out of 125 banks, eighteen were inspected (Table 2).

Table 2. Number of documented inspections, 1961–1969

Note: (*) In 1969, there were thirteen ordinary inspections and six ordered by the IEME. Sources: AHBE, Banca Privada, C. 929, C.930, C.931, C.932, C.956, C.957, C.958, C.970; AHBE, CSB, Sanciones, 299/01; AHBE, Inspección, C. 126, C.129, C.130, C.131 and from C.325/1 to C.448.

As in the previous decade, the banks inspected during the 1960s were generally small (regional, local, and industrial banks) and recently established. In 1965, of eighteen inspected banks, four were national, and the rest were small banks (four were local, three were regional, and seven were industrial banks). However, a significant shift occurred compared to the pre-1962 period, as the Bank of Spain ordered an exhaustive inspection of a large bank for the first time. At a meeting of the Bank’s Executive Board in December 1966, the board agreed that the Bank should also inspect large banks to avoid giving the impression that it was only concentrating on smaller institutions.Footnote 64 The 1967 inspection of Banco Hispano Americano, one of the Big Five banks at the time, marked a milestone in terms of supervision. In fact, alongside the inspection order for the Banco Hispano Americano, in 1967 the Bank of Spain published a report with precise instructions on how to conduct periodic inspections of larger banks.Footnote 65 The report highlighted several specific and particularly relevant aspects, including the study of affiliated and related companies to ensure that the bank did not apply any discriminatory policies in favor of these companies, the use of statistical sampling techniques, and the importance of providing sufficient statistical justification in inspection reports to enable the Bank of Spain to justify the imposition of sanctions. It also listed and described the tasks that inspection service members had to perform.

The inspection reports from the 1960s show that many of the inspected banks had problems with credit risk concentration, as well as with granting loans to the president of the institution, to affiliated companies, or to individuals closely related to the bank. For example, the 1967 inspection of the Banco de Béjar stressed “the inadequate instrumentation of the bank’s risks, since almost a quarter of them are held in unpaid bills and current account overdrafts, amounting to more than 95 million, which represents 259.85 per cent of the bank’s accounting equity.” The inspector also emphasized the excessive concentration of risks not only at the level of individuals or companies, but also at the sectoral level, since “the textile industry absorbs 56.9 percent of the bank’s risks.”Footnote 66 Consequently, credit risk was such an important issue for inspection that in 1968, the Bank of Spain proposed that the Ministry of Finance adopt stricter measures regarding credit risk concentration.Footnote 67 Around 1966, the first solvency problems emerged in local, small-sized banks, with these banks eventually going bankrupt and disappearing.Footnote 68

Another change in inspections during the 1960s was that inspectors started to analyze compliance with regulations on liquidity ratios and public funds. They also still focused on the payment of “extra tipos” or illegally high interest rates. The inspection reports for Banco Condal (1965), Banco de Vigo (1966), Peninsular (1966), Banco de Béjar (1967), and Siero (1968) reference the payment of illegally high interest rates. As reflected in the inspection reports, inspectors had to employ ingenuity and skill during fieldwork to detect and quantify the payment of illegally high interest rates, which the banks in question typically concealed.

The sanctioning structure designed with the 1946 Banking Law remained largely unchanged until the 1970s, since the 1962 law did not modify it. The only significant change was brought about by Decree 59/1967, which extended the sanctioning regime by allowing the Bank of Spain to apply a penalty interest rate to institutions that had failed to comply with the regulations on ratios. What remained unchanged, however, was the lack of measures against the institution’s administrators.Footnote 69 The sanction files indicate that, in some cases, the inspectors’ recommendations—ratified by the Bank of Spain—were to impose significant fines. However, the CSB continued to operate similarly to how it did before 1962, often recommending a substantial reduction in fines or issuing merely a warning. The reports from the CSB during those years (the last report is from 1969) thus highlight the corporatist nature of the institution and the markedly different treatment of various infringements. For example, while the payment of illegally high interest rates was a serious offence that warranted fines, the CSB recommended only a warning for offences related to banks granting loans through overdrafts, failure to repay bad debts, or undocumented loans. Unfortunately, not all the inspection reports we have located specify the sanctions ultimately imposed, making it difficult to assess how effective the CSB was in exerting pressure.

Banking Supervision During the Early 1970s

In the early 1970s, the government took several steps towards further liberalization. Between 1969 and 1971, it liberalized some interest rates and, starting in 1974, relaxed restrictions on the opening of branches, along with the rules governing the establishment of new banks. It also eliminated differences between commercial banks and industrial banks. However, intervention in banking activities through compulsory investment ratios remained in place. The gradual liberalization of branch opening stimulated competition, as banks used geographic expansion to attract customers. The increase in deposits was accompanied by credit growth, with a steep rise in private bank credit to the nonfinancial private sector. Consequently, the ratio of credit to GDP reached levels comparable to those in France and exceeded those in Italy and Germany.Footnote 70 As shown in Figure 1, the three indicators of competition employed reveal a significant decline in banking concentration and a decrease in the degree of centrality. Furthermore, a more sophisticated measure of competition, the Lerner Index, indicates a clear decrease in the market power of the banking industry from 1970 to 1983/1984.Footnote 71 Thus, despite the challenges encountered, the liberalization process successfully boosted competition. Although the period lies beyond the scope of this work, the economic problems associated with the economic crisis starting in 1975 and further exacerbated by the banking crisis that erupted in 1977 disrupted the liberalization agenda.

In terms of banking supervision, inspection activities in the first half of the 1970s continued the work initiated under the 1962 legislation. As noted, 1970 saw the abolishment of the Collaborating Office of the Ministry of Finance that had been working with the Bank of Spain. In the same year, the Bank of Spain set up its Private Banking Inspection Office. Banking supervision operated on two main fronts: statistical control and inspections, with the latter further categorized into ordinary (or periodic) inspections and single-issue inspections. The Bank of Spain’s Inspectorate increased and improved its task of information disclosure and statistical control, with support from the CIR. Regarding inspections, our examination of the reports documented in the sanction files of the CSB and the Private Banking Inspection Office sections yields the information presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Number of documented inspections, 1970–1977

Source: AHBE, Inspección, C.327, C.980, C. 2535, C.2552, C.2558; AHBE, CSB Sanciones, C.299; AHBE, Supervisión, C.6506, 6507, 6508.

As Table 3 illustrates, there was a significant increase in the number of inspected banks from 1972 onwards. This rise in inspections was partly due to those related to foreign exchange transactions, but it was not the only factor. In 1973 and 1974, the number of banks inspected—excluding inspections related to foreign exchange—reached thirty-six, substantially higher than in the 1960s. By this time, the growing risks associated with lending to companies linked to banks were already evident. Therefore, the Bank of Spain made significant efforts in the 1970s to increase the number of banks inspected, despite staff shortages. In 1974, it inspected 37% of the 107 banks, a significantly higher percentage than in the previous decade. In 1973, the Bank of Spain reported on inspection visits to banks such as Atlántico, Bilbao, Comercial para América, Hispano, and Popular, all of which served as delegated banks for foreign exchange operations.Footnote 72 The reports revealed various violations and irregularities in the handling of authorized foreign exchange transactions, which had previously been the remit of the IEME but were now under the central bank’s control. Despite these violations, the Bank did not impose any sanctions. Instead, the Bank of Spain’s Executive Council, after verifying the profits these banks had earned from their infractions, instructed them to halt such practices. As a preventive measure, the Bank of Spain demanded that the banks in question submit their foreign exchange positions daily at the close of operations.

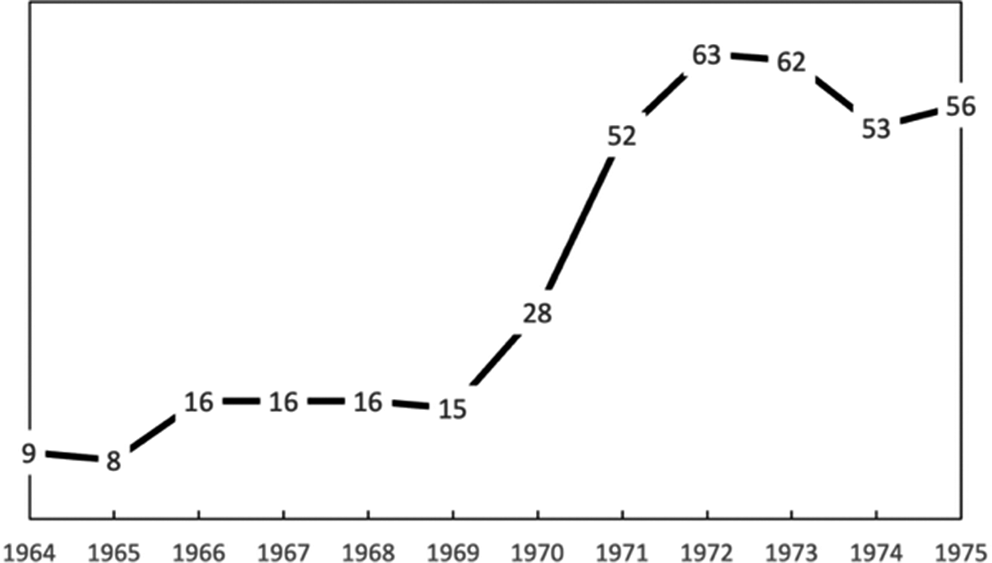

Regarding the number of inspectors, the Bank of Spain made a notable effort in the early 1970s to expand the staff. As shown in Figure 2 , the number of inspectors increased rapidly from twenty-eight in 1970 to sixty-three in 1972. However, despite this significant rise, it was still far below the number needed to fulfil the necessary inspection tasks. The Bank of Spain was aware of the technical difficulties involved in the work of bank inspectors. As in the early 1960s, it was not easy to recruit qualified personnel with sufficient technical knowledge. As mentioned, throughout the 1960s and 1970s, all inspectors came from the Bank of Spain’s staff in Madrid and its branches. These positions were not open to external candidates until 1979. From that point onward, there were annual open examinations, partly due to the urgent need for additional inspection staff prompted by the banking crisis.

Figure 2. Total number of inspectors, 1964–1975.

Source: AHBE, Libros. Escalafones del Personal y Plantillas, and AHBE, Supervisión, 26506 and 6507. Own elaboration.

During the early 1970s, most of the banks inspected were still small or medium-sized institutions. However, the Bank of Spain also conducted inspections of some large national banks, such as the Banco Central (1971, 1972) or the Banco Español de Crédito (1971). It is noteworthy that many of the problems identified in the inspections of the 1970s had persisted since the previous decade; the fact that the existing sanctioning regime applied had failed to address them was proof of its ineffectiveness. For example, the 1970 inspection of the Banco de Coca revealed problems that dated back to 1956, and which several inspections during the 1960s had already identified. Similarly, the 1970 inspection of Banco del Noroeste identified problems that the 1968 inspection had already noted.Footnote 73

It is also important to note that, in the years leading up to the 1977 crisis, the focus of inspection work gradually shifted. As mentioned, earlier inspections primarily targeted common infractions, such as applying unauthorized interest rates on assets and liabilities, overdrafts, improper fees, noncompliance with regulatory ratios, the improper payment of dividends, balance sheet irregularities, and obstruction of inspection processes. However, as the crisis approached, there was a heightened focus on the banking credit policies, with inspectors specifically evaluating the quality of loans and guarantees, scrutinizing loan renewals, flagging inadequate risk reporting to the CIR, and investigating potential links between loans and companies associated with members of the banks’ boards of directors.

The sample of inspections we analyzed for this study (Banco Rural, Norte, Echevarría, Peninsular, López Quesada, Exterior de España, Santander, Bilbao, Simeón, Sevilla, San Sebastián, Huesca, Madrid, General de Comercio, Condal, Rural y Mediterráneo, Banco Industrial Mediterráneo, Unión Industrial Bancaria, and Banco Coca) reveals intense competition for deposits and credits, evidenced by the payment of unauthorized liability interest rates and the irregular application of lending rates that deviated from official benchmarks. This occurred in various forms, including loans, bill discounting, and increasing the cost of credit by withholding a portion of the loan granted. Furthermore, there were instances of banks deliberately obstructing the inspection process, highlighting the challenges faced in enforcing compliance. Risk concentration and irregularities were particularly serious in the banks linked to the Rumasa holding company.Footnote 74 A case in point is Banco de Sevilla, inspected in 1972. The inspectors discovered that Banco de Sevilla’s lending practices exhibited clear favoritism towards the Rumasa companies. Direct risks associated with these companies accounted for 30% of the bank’s total risk exposure and 39.4% of its total resources, significantly exceeding the risk limits established for a bank’s exposure to a single individual or entity. There were also irregularities in the information the bank sent to the CIR, the systematic application of rates higher than those authorized in its lending operations, and the charging of commissions higher than those permitted.Footnote 75 Furthermore, the inspection uncovered conflicts in senior positions; for example, the same person exercised executive functions in Banco Meridional and Banco de Sevilla, and at the same time was the deputy general manager of Rumasa. Although inspectors detected such problems in many banks, the sanctioning system remained ineffective in driving meaningful changes in banks’ behavior. Another offence that inspectors continued to detect was the payment of irregular interest rates, often resulting in penalties of varying severity, such as fines or restrictions on the bank’s ability to expand branching.Footnote 76

Although supervisory practices improved during the 1960s and the early 1970s, numerous issues persisted. In addition to a chronic shortage of supervisory staff, there were two particularly pressing concerns. Firstly, inspections focused on individual banks rather than banking groups. This hindered a comprehensive understanding of the interconnections between banks and the relationships between banks and companies, which is crucial for accurately assessing the overall level of risk. Secondly, the sanctioning framework proved ineffective. The penalties imposed were generally insufficient and primarily targeted the institutions rather than addressing the behavior of individual administrators. Aside from the option of suspension, there were few mechanisms in place to correct the actions of those in leadership positions. At the same time, it was becoming increasingly clear that many banks—some the result of the 1962 Banking Law’s promotion of banking specialization—were facing significant problems. Consequently, banking supervision failed to prevent the banking crisis that erupted in 1977. The economic crisis of the 1970s severely affected the banking sector, which had strong links with industry and construction. Corporate bankruptcies and rising defaults led to higher nonperforming loan ratios, which reduced banks’ profitability. The impact was particularly severe on banks established under the 1962 law. Management problems, inadequate risk control, and intense competition for deposits pushed up operating costs and weakened stability. From 1977 to 1982, the crisis hit small and medium-sized banks, while in a second phase (1982–1985), it affected larger institutions. The crisis affected sixty-three of the 110 banks operating in 1977, representing almost 30% of assets and 18% of deposits. The government intervened in twenty-nine banks and expropriated 20 of the Rumasa group. It became one of the most significant financial crises in modern history, second only to the 2008 crisis.Footnote 77 The severity of the Spanish banking crisis served as a catalyst, driving the transformation of supervisory practices towards more modern and effective approaches.

Conclusions

After the Civil War, the most significant event in terms of banking supervision occurred when Franco’s authorities removed the Bank of Spain’s supervisory responsibilities and transferred them back to the Ministry of Finance, where they had been prior to 1921. Even before the war ended, regulations had granted the Minister of Finance the authority to set credit policy and occasionally inspect specific banks or bankers. Furthermore, the 1946 Banking Regulation Law made the DGBB and the CSB responsible for banking supervision, rather than the Bank of Spain.

Our findings show that both regulations and the banks themselves sought to limit competition in the banking sector, resulting in minimal control and banking inspection activities, especially in the ten years after the war. In fact, there was a shortage of human capital and resources dedicated to inspections, compounded by the lack of political will from the authorities to adopt more effective supervision. Moreover, the few archival records from that period indicate that inspections primarily entailed some limited off-site supervision based on the disclosure of accounting information, and they were typically aimed at ensuring regulatory compliance. Although the 1946 law deemed numerous behaviors punishable, it had little practical effect, as the sanctioning structure relied primarily on warnings and reprimands. Ultimately, the CSB was responsible for recommending sanctions to the Ministry, but it was generally in favor of reducing the severity of the penalties. It is evident that, in a context of noncompetition, supervision was not a key instrument of the Franco government during this period.

The changes in the Spanish economy during the 1950s were mirrored in the financial sector. Increased competition among banks, and between banks and savings banks, predictably coincided with a rise in banking inspections in the latter half of the 1950s. Interestingly, it was the banks themselves, through the CSB, that pressed for greater control over banks—particularly concerning the payment of illegally high deposit interest rates and the potential existence of unauthorized branches. In most cases, inspectors continued to focus on basic analysis of the balance sheet, but they were increasingly concerned about credit risk concentration. The banks inspected were generally local or regional entities, and there was no specific body of inspectors at the time, so accountants from the Ministry of Finance carried out these unsophisticated inspections. Increasing competition led to greater supervisory activity in the second half of the 1950s, but this oversight was guided more by the banks’ interest in reducing competition than by other issues. We should also recall the government’s interest in keeping interest rates low to finance its activities at a lower cost. Although inspectors were also concerned about matters affecting bank solvency, such as credit risk concentration, the CSB consistently demonstrated its corporatist nature by limiting the severity of sanctions. The virtual lack of supervision did not lead to banking instability primarily due to a relatively low (though increasing) level of banking competition, the banks’ adoption of agreements or self-regulation, and their investments in public debt to provide more liquidity.

The 1962 Banking Law marked a turning point in developing formal and modern banking supervision in Spain. Along with the nationalization of the Bank of Spain, one of the law’s key provisions was the clear and permanent transfer of supervisory authority over private banks to the central bank. This restoration of supervisory powers enabled the Bank of Spain to adopt a more comprehensive and multifaceted approach to regulation and oversight. The new law introduced some measures that reflect the Bank of Spain’s overriding concern with the growing competition in the Spanish financial sector, as well as the need to ensure banking stability and address credit risk issues. Firstly, it established the Private Banking Inspection Service, which expanded the Bank of Spain personnel, resulting in more frequent, thorough, and complex inspections. Secondly, it created a Risk Information Centre (CIR) within the Bank of Spain to oversee the credit operations of banks, savings banks, and other financial institutions by centralizing credit statistics and identifying exceptional risks. Furthermore, in 1969, the Inspection Service assumed responsibility for banks’ foreign exchange operations.

During the 1960s, the formalization of the Bank of Spain’s banking supervision progressed slowly but led to an increased volume of both periodic and extraordinary inspections. As a result, the inspection service expanded its human and organizational resources, and the number of inspectors quadrupled between 1965 and the onset of the banking crisis in 1977. In a significant shift, the inspection process began to cover the larger banks, which had not previously undergone exhaustive inspections. Despite the progress made, there were still obvious flaws in the banking inspections. Firstly, inspections focused on individual banks rather than banking groups. This limitation had significant negative consequences in the medium term because information on banking groups is crucial for accurately assessing the overall risk level. Secondly, the main goal of banking supervision was still to support the Franco regime’s interventionist economic policies through legal ratios and interest rate controls, rather than maintaining the overall health and stability of the banking sector. Thirdly, the sanctioning structure remained unchanged and proved to be ineffective and very lenient. The CSB responded to most detected irregularities with recommendations or trivial penalties that had little impact on banking operations. In this regard, the CSB, as an institution representing the banking industry, continued to play a prominent role in limiting sanctions, as it had done in previous years. Moreover, despite the increasing focus on inspecting credit risk concentrations, there is no evidence that these inspections involved a thorough analysis of banks’ asset quality or the actions of their managers. Finally, although both the Inspection Service and the CIR received additional funding, they were still affected by notable staff shortages. This shortfall hindered the effectiveness of inspections during a period of economic expansion, resulting in the accumulation of imbalances and risks that would escalate in the following decade. Although the banking system in the 1960s was marked by relative stability—aside from some issues affecting smaller banks—the limited implementation of prudential measures and ineffective sanctions meant that the deterioration of the economic situation in the 1970s exposed the system’s structural weaknesses. Then, an inadequate supervisory framework ultimately failed to prevent one of Spain’s worst financial crises from occurring in 1977.

Acknowledgments

A first draft of this paper was presented at the conference “Les banques centrales, acteurs politiques ? (XVIIIe–XXIe siècle),” held at the Banque de France, 5–6 December 2024. We want to thank all participants for their helpful comments and suggestions. We are particularly grateful to Sean Vanatta, Jean Luc Mastin, and an anonymous referee for their insightful and constructive feedback, as well as to the journal’s editor for his valuable guidance. We also thank the staff of the AHBE, especially Elena Serrano and Rosario Calleja, for their continuous and invaluable support. The usual disclaimer regarding any remaining errors and omissions applies. We gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Technology (PID2023-149820NB-I00), the Generalitat Valenciana (PROMETEO 2024/86), and the Bank of Spain (Research Grant 2022–23).