1 What Is Creative Agency and Why Does It Matter?

This section introduces our conception of creative agency, building on our and others’ previous work on creative self-beliefs and our updated model of Creative Behavior as Agentic Action (CBAA). Our goal is to describe its role in understanding how individuals convert creative potential into meaningful action. We begin by examining the philosophical foundations of human agency before offering our definition of creative agency and exploring key components related to that definition.

How can we live in a predetermined universe yet still be able to make novel choices and bring about alternative possibilities? This question highlights a longstanding area of debate in philosophy, psychology, and the sciences. Several scholars have long dismissed human agency as a mental illusion, arguing that such beliefs belong to “folk psychology” and are incompatible with a deterministic universe (Churchland, Reference Churchland1981, Reference Churchland1986; Sapolsky, Reference Sapolsky2023). These arguments claim that human actions are governed by predetermined physical laws and properties of our brains.

In contrast, scholars like psychologist Albert Bandura (e.g., Bandura, Reference Bandura1986, Reference Bandura2001) argue that humans are active agents who exercise control over their behaviors. This agency allows them to uniquely shape their lives and the environment around them. More specifically, Bandura (Reference Bandura2001) does not reject the influence of biology or the way phenomena operate in the physical world. He rejects the view that biology or physical structures predetermine behavior:

Human evolution provides bodily structures and biological potentialities, not behavioral dictates. Psychosocial influences operate through these biological resources to fashion adaptive forms of behavior.

This perspective offers a more nuanced view that goes beyond simple either/or claims. For example, it challenges the idea that human behavior must be either entirely predetermined and aligned with scientific laws of the universe, or freely chosen and thereby making humans an anomalous and incompatible exception to those laws. Rather, Bandura’s (Reference Bandura2001) perspective is a both/and view. It recognizes both the possibility for the physical universe to operate under predetermined laws and for humans to still exercise some level of choice and control over their behaviors and actions in the world around them.

Philosopher Christian List provides a compelling argument in favor of this both/and perspective. More specifically, List (Reference List2023) asserts that accepting determinism at the physical level (i.e., “physical possibilities” governed by the laws of physics) does not require rejecting the idea that humans can exercise some level of choice and control over their actions and bring about new possibilities (i.e., “agentic possibilities,” which have a degree of openness that we have some control over). According to List, physical possibilities and agential possibilities are compatible because they operate at different levels. An example might help clarify this compatible view.

Just as coding has a set of syntax rules that govern how the programming language operates (“physical possibilities”), human coders can exercise choice and creativity (“agential possibilities”) in how they work with that programming language to create a vast array of programs and applications. The programming rules constrain but do not predetermine the possibilities for how coders develop new computer applications. The same can be said for a vast array of human endeavors, for instance:

In the arts, sculptors exercise their agency by making creative choices within the constraints of a specific medium (e.g., clay), and poets often work within a formal structure (e.g., haiku).

In business, employees exercise agency in how they approach tasks and provide goods and services to customers while adhering to constraints such as company practices, government regulations, and brand guidelines.

In education, teachers exercise agency by designing unique lessons and tailoring their teaching methods to student needs within the constraints of curricular standards and school policies.

Our goal here is not to go too far down a philosophical rabbit hole but to provide a backdrop for realizing that human agency is always constrained. Those constraints, however, do not preclude people from intentionally making choices about when and how they will act in certain situations. Moreover, those choices can lead to new and meaningful changes in their lives and the world around them.

What Is Creative Agency?

Scholars have conceptualized creative agency in various ways outside of psychology. Daniel X. Harris, director of the Creative Agency Lab, for instance, views creative agency from a socio-cultural perspective informed by posthumanist, new materialist, and affective theories (Harris, Reference Harris2021), emphasizing an active, responsive, relational, and ethically engaged way of being in the world (Harris, Reference Harris2023). Oliver Bown and Jon McCormack apply the concept to artificial life (i.e., non-human and computational systems), defining creative agency as “the degree to which [a system] is responsible for a creative output” (p. 255).

We define creative agency from the psychology of human creativity as:

The intentional and self-directed capacity to envision and enact new and meaningful actions within the existing constraints of a particular context which can bring about changes in our lives and the world around us.

This definition encompasses two key elements. First, the “creative” aspect addresses both novelty and meaningfulness, aligning with standard definitions of creativity (Plucker et al., Reference Plucker, Beghetto and Dow2004; Runco & Jaeger, Reference Runco and Jaeger2012). Second, the “agentic” aspect emphasizes the intentionality of choices and the self-directed nature of actions, consistent with Bandura’s (Reference Bandura2001) conception of agentic action.

We also recognize that agentic action occurs within physical, sociocultural, and psychological constraints of a given context (Bandura, Reference Bandura2001; List, Reference List2023). The central issue is not whether people can exercise creative agency, but rather what factors facilitate or impede it. Indeed, just because people have the capacity to exercise creative agency does not mean that they will.

Exercising creative agency is resource-intensive. As Baumeister (Reference Baumeister2008) has argued, exercising intentional choice and control over thoughts and actions requires expending psychological resources. Indeed, there is evidence that making choices and exercising control over one’s thoughts and behaviors in one task can deplete performance on subsequent tasks (Baumeister et al., Reference Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Muraven and Tice1998; Muraven & Baumeister, Reference Muraven and Baumeister2000; Vohs et al., Reference Vohs, Baumeister and Schmeichel2008). Although the assertion that exercising agency can deplete subsequent performance makes sense, recent work (Forestier et al., Reference Forestier, de Chanaleilles, Boisgontier and Chalabaev2022; Hagger et al., Reference Hagger, Chatzisarantis and Alberts2016) has cautioned against describing this in simple or singular terms, such as “ego depletion.”

Rather, researchers recommend taking a more nuanced, multifaceted, and dynamic view. Forestier and colleagues (Reference Forestier, de Chanaleilles, Boisgontier and Chalabaev2022) have, for instance, recommended describing the costs of exercising agency as “self-control fatigue,” which can impair people’s capacity, resources, and willingness to exert effort. They define self-control fatigue as “a temporary impaired effortful self-control act caused by an initial effortful self-control act that aimed to resolve a motivational conflict and decreased self-control resources, willingness and/or capacity” (p. 25).

Indeed, there are various personal factors, social pressures, and restrictions that can impede creative agency (Brehm, Reference Brehm1966). Consequently, people will likely exercise creative agency only when they believe the benefits outweigh the potential physical, psychological, and social costs. Put simply, creative self-beliefs matter when it comes to exercising creative agency.

Creative Agency Beliefs

Understanding how people exercise creative agency requires examining the key decisions they encounter when considering creative action. In 2019, we introduced a model of CBAA (Karwowski & Beghetto, Reference Beghetto2019). The CBAA model presented an empirically testable set of assertions derived from our own earlier work (Beghetto, Reference Beghetto2006; Beghetto & Karwowski, Reference Beghetto, Karwowski, Karwowski and Kaufman2017; Karwowski, Reference Karwowski2011) as well as the contributions of others (e.g., Bandura, Reference Bandura1997; Tierney, Reference Tierney1997; Tierney & Farmer, Reference Tierney and Farmer2002) on creativity and self-beliefs.

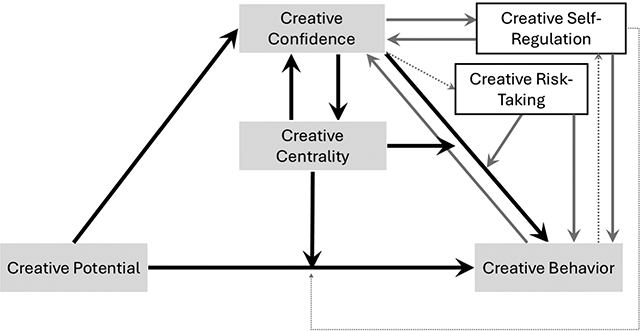

As this research program evolved, we recognized the need to expand this model to offer a more holistic, unified, and empirically testable theoretical account of creative agency. In our expanded model, creative agency is conceptualized as a series of interrelated decisions informed by four core self-beliefs:

Creative confidence: Belief in one’s ability to think and act creatively.

Creative centrality: Belief that creativity is a central aspect of one’s identity and personal values.

Creative risk-taking: Belief that the benefits of engaging in creative actions outweigh potential costs or risks.

Creative self-regulation: One’s ability to use strategies and skills necessary for engaging with ill-defined creative tasks and overcoming challenges encountered along the path to creative solutions.

We also identified the need for a refined model to address lingering conceptual and methodological issues that have led to inconsistent findings across studies on these self-beliefs (Beghetto & Karwowski, Reference Beghetto, Karwowski, Karwowski and Kaufman2017, Reference Beghetto, Karwowski, Beghetto and Corazza2019). Updating our model thus provides an opportunity to clarify and better align these concepts with the design of future studies, enhancing the field’s understanding of how creative agency beliefs facilitate the translation of creative potential into action.

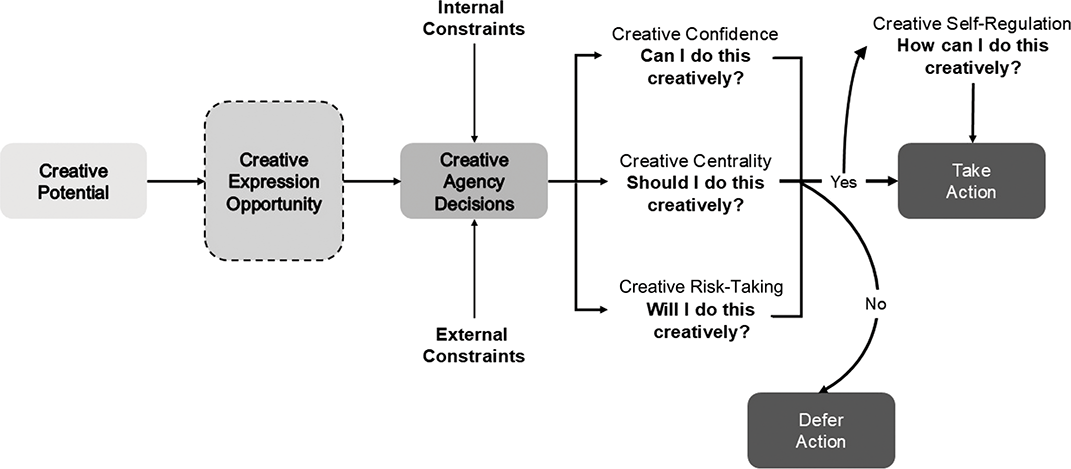

Our updated model of CBAA (building on Karwowski & Beghetto, Reference Beghetto2019; explored fully in Section 6) identifies four critical decisions that shape whether and how individuals convert creative potential into creative action (see Figure 1):

1. Can I do this creatively? (Creative Confidence) This first decision is informed by people’s creative confidence beliefs (fully described in Section 2). Creative confidence encompasses whether people believe they can think and act creatively. This belief is comprised of two interrelated sub-beliefs:

A general, trait-like belief in one’s creative ability;

A specific, state-like confidence when facing creative challenges.

2. Should I do this creatively? (Creative Centrality) This decision examines whether people value creativity and view it as central to their identity (detailed in Section 3), including:

Whether people believe there is inherent value in being creative;

How people assess the personal meaning of creative action;

How these value judgments influence creative behavior;

The role of sociocultural factors in shaping creative centrality beliefs.

3. Will I do this creatively? (Creative Risk-taking) This decision focuses on risk assessment (discussed in Section 4), specifically:

Weighing benefits against potential costs of creative action;

Willingness to embrace uncertainty;

Ability to face potential setbacks;

The role of prior experiences in risk-taking decisions;

The distinction between process-related and product-related risks;

The influence of contextual factors on risk assessment and decision-making.

4. How will I do this creatively? (Creative Self-regulation) This final decision involves implementation strategies (described in Section 5), including:

Using cognitive and behavioral strategies;

Managing thoughts, emotions, and actions;

Operating across three phases:

o Forethought (goal setting, strategy planning);

o Performance (monitoring progress, adjusting strategies);

o Self-reflection (evaluating outcomes, learning for future tasks).

These four components work together as an integrated system within the CBAA model. While each component can be examined independently (and are individually discussed in Sections 2–5), they function interdependently to influence how individuals assess and engage in creative action. Their combined influence determines whether and how creative potential is converted into meaningful creative behavior, as detailed in Section 6.

As illustrated in Figure 1, these decisions become activated when we encounter situations requiring new thought and action. This activation occurs in situations such as when our previous approaches no longer serve us effectively, when we identify opportunities to create something new, or when existing solutions prove insufficient.

Figure 1 Creative agentic decisions necessary for converting potential into action

Figure 1Long description

The flowchart traces the path from Creative Potential to action. Creative Potential leads to a Creative Expression Opportunity. This opportunity influences Creative Agency Decisions, which are shaped by Internal and External Constraints. Decisions involve assessing Creative Confidence (Can I do this creatively?), Creative Centrality (Should I do this creatively?), and Creative Risk-taking (Will I do this creatively?). A 'Yes' outcome leads to Take Action, influenced by Creative Self-Regulation (How can I do this creatively?). A 'No' leads to Defer Action. The chart shows how potential and opportunity, filtered through agency decisions based on internal factors and constraints, determine if creative action is taken or deferred, with self-regulation guiding execution.

These decisions are shaped by both internal factors (such as our agency beliefs) and external factors (such as social and environmental contexts). To illustrate how these four decision points and their associated beliefs operate in practice, we present two contrasting scenarios. These scenarios demonstrate how creative agency beliefs can either enable or constrain creative action in real-world settings.

Creative Agency Beliefs in Action: Two Scenarios

Scenario 1: Diminished Creative Agency Beliefs

Consider Chris, a recently promoted shift manager at a popular restaurant. Chris notices persistent inefficiencies in the staffing scheduling process and recognizes an opportunity to creatively address this problem by introducing a new artificial intelligence (AI) scheduling tool.

However, Chris quickly experiences self-doubt (Creative Confidence). Despite recognizing that the AI tool is innovative, Chris questions their ability to successfully present and implement the idea. Although Chris has been generally confident in previous roles, the specific challenge of advocating for a technological change causes state-like uncertainty about their ability to convince senior management.

Chris also struggles to evaluate whether pursuing this creative solution aligns with their values and identity (Creative Centrality). While Chris generally values efficiency and innovation, they currently do not view creativity or proposing new ideas as central aspects of their professional identity, particularly within their new role. Additionally, the organizational culture seems to prioritize stability and adherence to established practices, further diminishing Chris’s perception of creativity as a central or valued aspect of their new shift-manager identity.

Facing uncertainty about senior management’s reaction, Chris carefully weighs the benefits against the potential personal and professional costs (Creative Risk-Taking). The potential advantages of improved efficiency seem promising, but Chris perceives significant risks associated with stepping outside traditional expectations and challenging established processes. Concerned about rejection, loss of credibility, or negative career consequences, Chris concludes that the risks outweigh possible rewards, further discouraging creative action.

Finally, Chris lacks clear strategies for managing uncertainty, emotions, and potential setbacks in moving forward with this creative solution (Creative Self-Regulation). Without established approaches for handling potential criticism, adapting their proposal to senior management expectations, or persisting in the face of initial resistance, Chris feels ill-equipped to successfully navigate the uncertainties of implementing this solution.

Taken together, these diminished agency beliefs (i.e., low creative confidence, limited creative centrality, heightened risk perception, and insufficient self-regulatory strategies) constrain Chris’s decision-making, leading them ultimately to abandon the idea. Rather than taking creative action, Chris decides to maintain the inefficient but familiar scheduling process.

Scenario 2: Robust Agency Beliefs

Now, let’s imagine Dr. Jones, a college instructor teaching an introductory physics course designed for nonscience majors. Dr. Jones frequently hears students express frustration, complaining that the course content lacks relevance to their lives. Recognizing an opportunity for creative improvement, Dr. Jones develops a generative AI chatbot called AppliedScience Bot to help students explore practical connections between physics concepts and their everyday experiences.

Initially, Dr. Jones faces some internal doubts (Creative Confidence). While generally confident about their ability to introduce innovative teaching methods, recent faculty discussions about generative AI perpetuating scientific misconceptions cause some initial hesitation. However, Dr. Jones is confident that the AppliedScience Bot is different and believes it can help students see the relevance in what they are learning.

Dr. Jones also strongly believes that creativity and innovation in teaching are central to their professional identity (Creative Centrality). They view creative experimentation as a core value of effective instruction and perceive implementing AppliedScience Bot as aligned with their teaching philosophy and identity. This belief strengthens Dr. Jones’s commitment to exploring new educational solutions despite the possibility of potential criticism.

In assessing risks, Dr. Jones acknowledges the concerns colleagues have raised about inaccuracies associated with generative AI but carefully weighs potential costs against the benefits of making physics more relevant to students (Creative Risk-Taking). Convinced that clearly communicating potential limitations to students can mitigate risks, Dr. Jones decides that the educational value of enhancing student engagement significantly outweighs potential drawbacks. Based on this assessment, Dr. Jones decides to embrace the uncertainty of implementing this instructional innovation.

Aware that resistance or criticism might arise, Dr. Jones proactively prepares strategies to manage potential obstacles (Creative Self-Regulation). When colleagues express skepticism midway through the semester, Dr. Jones is ready and provides a demonstration video illustrating AppliedScience Bot’s effective use and positive student feedback describing how the chatbot increased engagement and relevance. Dr. Jones is able to effectively address colleagues’ concerns and foster greater acceptance, prompting some colleagues to ask about adopting the chatbot in their courses.

Ultimately, Dr. Jones’s robust agency beliefs (i.e., strong creative confidence, clear identification with creativity’s central role in their teaching identity, willingness to embrace creative risks, and effective self-regulatory strategies) resulted in a successful creative outcome. Reflecting on this experience, Dr. Jones decides to pursue the development of an additional chatbot to support further student engagement and learning.

Why Does Creative Agency Matter?

As we have discussed, when people exercise their creative agency, they can convert their creative potential into creative actions and achievements. Creative agency is, therefore, crucial at the individual and societal level. At the individual level, exercising creative agency can help us more productively navigate the uncertainties we face in everyday life. It can contribute to a sense of purpose, give our lives meaning, and promote well-being (Kaufman, Reference Kaufman2023; Zielińska et al., Reference Zielińska, Lebuda and Karwowski2023). It allows us to play a central role as the creative authors of our learning and lives – contributing to more positive and transformative futures for ourselves and others (Beghetto, Reference Beghetto2023).

On a broader scale, exercising our agency plays a central role in the coevolution of individuals and cultures, simultaneously shaping our environment and influencing our development (Bandura, Reference Bandura2001). Exercising our creative agency can also contribute to societal progress and innovation. It helps in addressing complex societal issues and longstanding inequities, promoting economic growth, and bringing about positive social change (Sternberg & Karami, Reference Sternberg and Karami2024).

In this way, developing healthy beliefs in our ability to exercise creative agency is not simply an additive luxury. Rather, it is necessary for healthy human flourishing and societal progress. Prior research on whether people believe they have choices and control over their own lives (Baumeister, Reference Baumeister2008; Vohs & Schooler, Reference Vohs and Schooler2008) suggests that people who lack such beliefs may exhibit decreased prosocial behavior and increased antisocial behavior, thereby hindering the motivation necessary for individual and societal progress.

Therefore, understanding creative agency and how it can be supported is a critically important goal for the social sciences, as agency plays a central role in individual and societal growth and survival. This issue takes on added importance in the age of GenAI, as such technological advancements present both positive possibilities for enhancing human agency (using GenAI to extend creative capabilities) and potential threats to people’s willingness to exercise their agency (e.g., people deferring their creative thinking and actions to machines) (Faiella et al., Reference Faiella, Zielińska, Karwowski and Corazza2025; Reich & Teeny, Reference Reich and Teeny2025).

Overview of the Remaining Sections of This Element

In the remainder of this volume, we take a much closer and more detailed look at the theory and research on the four creative agency beliefs: creative confidence, creative centrality, creative risk-taking, and creative self-regulation. We discuss the early, contemporary, and future directions of theory and research on each of these beliefs.

We then offer theoretical assertions to guide researchers in exploring how these beliefs work together to convert creative potential into creative action (Section 6). Finally, we conclude with practical questions and strategies for cultivating creative agency (Section 7). Having introduced the nature and importance of creative agency, the remaining sections examine each component in detail, beginning with creative confidence in Section 2.

2 Creative Confidence: Can I Do This Creatively?

Creative confidence refers to the belief in one’s ability to think or act creatively across various performance domains (Beghetto & Karwowski, Reference Beghetto, Karwowski, Reiter-Palmon and Hunter2023; Karwowski et al., Reference Karwowski, Han and Beghetto2019a). The psychological study of this construct emerged from creativity researchers’ broader efforts to understand creative behavior and its underlying determinants.

Before discussing the historical roots and specific dimensions of this belief, it is important to clarify our use of the term creative confidence. While the concept of creative self-efficacy (CSE) is well-established and likely more familiar to many readers, we intentionally use the broader term creative confidence because it is grounded in recent theoretical and empirical developments within creativity research (e.g., Beghetto & Karwowski, Reference Beghetto, Karwowski, Karwowski and Kaufman2017, Reference Beghetto, Karwowski, Beghetto and Corazza2019, Reference Beghetto, Karwowski, Reiter-Palmon and Hunter2023; Karwowski et al., Reference Karwowski, Han and Beghetto2019a, Reference Karwowski, Lebuda, Beghetto, Kaufman and Sternberg2019b).

Our model of CBAA views creative confidence as encompassing CSE. Specifically, CSE represents the more state-like aspect of confidence beliefs related to specific creative tasks. The creative confidence construct provides a more nuanced framework, helping to resolve a longstanding misalignment in the literature that stemmed from the use of trait-like items in early CSE measures (e.g., “I am good at coming up with new ideas”).

As Bandura (Reference Bandura, Pajares and Urdan2006, Reference Bandura2012) cautioned, such items reflect general confidence rather than the more specific judgments characteristic of self-efficacy beliefs. This critical distinction and the broader concept of creative confidence will be explored in more detail later in this section. Clarifying this terminological shift is essential for understanding recent research developments in this area.

Historical Roots

Interest in human creativity dates back to ancient civilizations (Glăveanu & Kaufman, Reference Glăveanu, Kaufman, Kaufman and Sternberg2019) and extends beyond the field of psychology. For instance, Alfred North Whitehead’s philosophical work Process and Reality (Reference Whitehead, Griffin and Sherburne1929) is often credited with popularizing the concept of creativity in scholarly discourse. Whitehead viewed creativity not as a psychological trait but as a metaphysical principle of novelty, emergence, and the continual process of becoming.

Within the psychology of creativity, Joy Paul Guilford’s Reference Guilford1950 presidential address to the American Psychological Association is widely regarded as a pivotal moment, marking the beginning of systematic psychological research on human creativity. Importantly, we argue that Guilford’s address also laid the foundation for research into creative confidence. Guilford explicitly emphasized the role of individual differences in creative expression, stating:

Whether or not the individual who has the requisite abilities will actually produce results of a creative nature will depend upon [ … ] motivational and temperamental traits.

Guilford further discussed a “creative pattern” characteristic of individuals who make creative contributions. This pattern represents a set of enabling factors that facilitate the expression of creative behavior. Some of these factors are more deterministic (biology, environment), and others are more dynamic and personally determined. One of the personal determining factors that Guilford mentioned was self-confidence (Guilford, Reference Guilford1950, p. 444).

Although Guilford did not provide further elaboration on the role self-confidence plays in creative behavior, this recognition is reflected in much contemporary work on creative agency beliefs. As we noted in our introduction, contemporary work on creative agency beliefs examines the role those self-beliefs, such as creative confidence, play in converting creative potential into creative actions and achievements.

Tracing Creative Confidence from Guilford to Bandura

Although shades of Guilford’s assertions can be recognized in contemporary work on creative confidence beliefs, Albert Bandura’s work has had the clearest and most direct influence on the development of related theory and research within the field of creativity studies. This is not too surprising given that Bandura’s social cognitive theory (Bandura, Reference Bandura2001) provides extensive theoretical assertions grounded in empirical work, that explain how confidence beliefs influence agentic action.

Bandura asserted that no factor is more central to exercising personal agency than people’s confidence in their ability to exercise control in their lives:

Among the mechanisms of personal agency, none is more central or pervasive than people’s beliefs in their capability to exercise some measure of control over their own functioning and over environmental events.

Bandura’s emphasis on the central role of confidence beliefs in human agency provided a strong foundation for creativity researchers. This foundation helped researchers understand how creative confidence plays a role in determining whether individuals will take creative action and contribute to their own lives and the world around them.

Bandura specifically conceptualized this phenomenon not as “confidence” but as “perceived self-efficacy.” Bandura (Reference Bandura1997) defined self-efficacy as “beliefs in one’s capabilities to organize and execute the courses of action required to produce given attainments” (Bandura, Reference Bandura1997, p. 3). It is thereby not surprising that creativity researchers borrowed this concept and adapted it to the field of creativity studies by calling it “creative self-efficacy.” In what follows, we briefly trace how this borrowed and adapted concept of creative self-efficacy served as a starting point for work on creative agency beliefs and why we recommend incorporating it into the broader concept of creative confidence beliefs.

Borrowing and Adapting the Concept of “Self-Efficacy”Footnote 1

Early mentions of CSE appeared in the literature in the mid-1990s. Ford (Reference Ford1996) specifically referred to “capability beliefs,” highlighting both self-confidence and creative self-image as elements within the “expectations and emotions that facilitate creative actions” (p. 1123, table 2). Plucker and Runco (Reference Plucker and Runco1998) directly referenced “creative self-efficacy” in their call for creativity researchers to examine both task-specific and task-general aspects of creative production “during each creative moment” (p. 37).

Tierney (Reference Tierney1997) and Tierney and Farmer (Reference Tierney and Farmer2002) were among the first to empirically examine the role of CSE in workplace creativity. They defined CSE as “the belief one can produce creative outcomes” (Tierney & Farmer, Reference Tierney and Farmer2002, p. 1138) and developed brief, trait-like measures to assess it.

These scales typically employed items reflecting general creative confidence, such as “I feel that I am good at generating novel ideas” and “I have confidence in my ability to solve problems creatively” (Tierney, Reference Tierney1997; Tierney & Farmer, Reference Tierney and Farmer2002), rated on Likert-type scales. Tierney and Farmer’s (Reference Tierney and Farmer2002) influential study, demonstrating CSE as a significant predictor of creative performance, became highly cited and prompted further research.

Subsequent research often adopted this trait-like approach to measuring CSE. For instance, similar three-item scales were developed using trait-like self-assessments such as “I am good at coming up with new ideas” (Beghetto, Reference Beghetto2006) or “I think I am creative” (Karwowski, Reference Karwowski2011). In response to calls for more nuanced measures, later efforts included multi-item scales like the Short Scale of the Creative Self (SSCS), which expanded the number of items that assessed trait-like CSE and included items measuring creative centrality (Karwowski et al., Reference Karwowski, Lebuda and Wiśniewska2018).

Research using these types of CSE measures expanded significantly, examining correlates, antecedents, mediating/moderating roles, and use across various domains (e.g., business, psychology, and education). A central concern has been the relationship between measured CSE and creative outcomes. Meta-analyses (Haase et al., Reference Haase, Hoff, Hanel and Innes-Ker2018) indicate that such CSE measures account for approximately 8% to 20% of the variance in nonself-reported creative outcomes and a higher percentage (20% to 53%) in self-reported outcomes (Farmer & Tierney, Reference Farmer, Tierney, Karwowski and Kaufman2017, p. 37).

However, the relationship between CSE and creative outcomes has yielded variable results, ranging from negligible to moderate effects (see Beghetto & Karwowski, Reference Beghetto, Karwowski, Karwowski and Kaufman2017, for a discussion). While many factors contribute to this variability, one significant reason relates to how the concept of self-efficacy was borrowed and adapted, particularly regarding the conceptualization and measurement practices, which we discuss in the following section.

The Benefits and Drawbacks of Conceptual Borrowing “Self-Efficacy”

Borrowing and adapting concepts from related fields comes with both strengths and limitations, some of which need to be addressed and corrected to ensure that research on creative agency beliefs contributes to knowledge and practice.

Conceptual borrowing from related (or distinct) fields can help to grow the conceptual foundations of a field (Ambrose, Reference Ambrose2015). Indeed, work on CSE is one of the most widely discussed and studied of creative agentic beliefs. As of this writing, a simple Google Scholar search on “creative self-efficacy” returns more than 20,000 results. That said, conceptual borrowing also comes with its share of challenges and drawbacks (Berkovich, Reference Berkovich2020), including distorted understandings, negative views of how the borrowed concept is used, and negative outside opinions of the work based on the borrowed concepts.

Consequently, scholars working with borrowed concepts often need to address and correct issues through retrofitting, renaming, and further specification of the measurement of these concepts to ensure that they are relevant and meaningful for research and practice (Ambrose, Reference Ambrose2015; Berkovich, Reference Berkovich2020). These retrospective “conceptual retractions” and corrections for borrowed concepts are both beneficial and necessary to promote better communication and indicate the positive growth of a field of study.

The same can be said of CSE. As we have discussed in detail elsewhere (Beghetto & Karwowski, Reference Beghetto, Karwowski, Karwowski and Kaufman2017), initial scales used to measure CSE have resulted in some conceptual distortions of Bandura’s concept of self-efficacy. These distortions diminish the accuracy and predictive power of CSE in relation to creative action. Therefore, some corrective action is required both in how the borrowed concept is described and measured.

Limitations of Traditional CSE Measures

While initial CSE scales offer potentially valuable insights into creative ideational confidence, they often fail to capture the performance-based nature of self-efficacy beliefs that Bandura originally conceptualized. This stems from the tendency for these early scales to use global and trait-like items, rather than dynamic states that fluctuate depending on the specific task, context, and the individual’s psychological state (Beghetto & Karwowski, Reference Beghetto, Karwowski, Karwowski and Kaufman2017). This static approach obscures the nature of self-efficacy, which is influenced by various factors like prior experiences, feedback, and the perceived difficulty of the task.

Another limitation of global measures of CSE scales is that they use “indefinite” items that “do not specify the activities to be performed, at what level of attainment, the nature of the goals they are striving for, and what those ‘valued outcomes’ and ‘challenges’ are” (Bandura, Reference Bandura2012, p. 16). It is therefore not surprising that more global, trait-like CSE measures tend to yield weak to modest relationships with actual performance (Haase et al., Reference Haase, Hoff, Hanel and Innes-Ker2018). These measures can also introduce potential confounds between self-efficacy beliefs about creative capabilities and the effects of those beliefs (Beghetto & Karwowski, Reference Beghetto, Karwowski, Karwowski and Kaufman2017). As Bandura (Reference Bandura2012) has cautioned:

These types of global measures of self-efficacy usually bear weak relation both to domain-related self-efficacy beliefs and to behavior … Measures of general self-efficacy not only have problems of predictiveness. Most of them are seriously confounded as well. For the most part, they assess the cognitive, motivational, affective, decisional, and behavioral effects of self-efficacy rather than peoples’ beliefs in their capabilities.

Figure 2 contrasts the traditional, global approach with a CSE measure aligned with Bandura’s (Reference Bandura, Pajares and Urdan2006, Reference Bandura2012) recommendations, highlighting the difference in specificity.

Figure 2 Difference between global and conceptually aligned measures

Figure 2Long description

The image shows two panels, A and B, comparing different ways to measure creative self-efficacy. Panel A, titled Global Measures, presents two scales. The first is Creative Self-Efficacy (Beghetto, 2006), with items like I am good at coming up with new ideas, I have a lot of good ideas, and I have a good imagination, with a rating scale of 1 through 5, ranging from Not True to Very True. The second scale in Panel A is Creative Self-Efficacy Items (Karwowski et al. 2011), with items such as "I know I can efficiently solve even complicated problems, I trust my creative abilities, My imagination and ingenuity distinguish me from my friends, Many times, I have proved that I can cope with difficult situations, I am sure I can deal with problems requiring creative thinking, and I am good at proposing original solutions to problems, with a rating scale of 1 through 5, ranging from Definitely not to Definitely yes.

Panel B, titled Conceptually Aligned Measure, presents a scale titled Creative Self-Efficacy: Creative Idea Development Science. It reads: Please rate how certain you are that you can come up with, share, and develop a creative idea into a science project that others recognize as creative. Rate your degree of confidence by recording a number from 0 to 100 using the scale given below. The scale from 0 to 100 ranges from Cannot do it at all to Highly certain can do. The tasks are: Come up with a creative idea in science class, Share my creative idea with only my teacher, Share my creative idea with the entire class, Develop my idea into a creative science project, Develop a project that peers and teachers think is creative, and Develop a project that science fair judges think is creative.

As illustrated in Figure 2, the difference between traditional measures of CSE and a more conceptually aligned CSE measure is apparent. The global measures speak to more trait-like and general appraisals of creative confidence, whereas the more aligned measure focuses on confidence tailored to a particular domain of activity (e.g., idea development in science).

Moreover, the aligned measure assesses confidence in different types and levels of performance. Logically (and likely empirically), this measure would be a stronger predictor of a student’s demonstrated ability to develop a creative idea into a creative science project that external audiences would recognize as creative.

Again, this is not to say one measure is necessarily better than the other. Instead, it highlights that creativity researchers should carefully consider what questions they seek to address when determining how to measure this creative agency belief. In some cases, researchers may decide to use one type over the other (e.g., use tailored measures when the question pertains to actual performance). In other cases, researchers may choose to use both types of measures (e.g., when attempting to understand how more trait-like measures work in conjunction with more tailored measures).

From a theoretical perspective, individuals with high general creative confidence (e.g., those who strongly endorse statements like “I can come up with creative solutions to problems”) would likely demonstrate higher confidence in creative performance in specific activity domains (e.g., “I can come up with a creative solution to this type of interpersonal problem”). This contrasts with those who have lower general creative confidence. However, because specific knowledge and experience within domains play a role in actual creative performance (Baer, Reference Baer2015), we expect that more tailored measures of creative confidence would be a more robust predictor of performance in specific spheres of creative activity (Bandura, Reference Bandura2012).

Empirical evidence supports this theoretical assertion. Karwowski et al. (Reference Karwowski, Han and Beghetto2019a) demonstrated that global measures of creative confidence predict domain-specific creative confidence, which in turn more strongly predicts creative task performance than global measures alone. This hierarchical relationship highlights the advantage of combining broad, trait-like measures and tailored, domain- or task-specific measures to better understand the relationship between creative confidence and performance.

Our goal in discussing the limitations of borrowing the self-efficacy concept for creativity research does not negate the value of global CSE scales. Rather, it highlights the need for more precise conceptual and measurement approaches while acknowledging the contributions of existing measures.

As research on creative agency beliefs continues to develop, it is essential that researchers further specify how creative confidence is described and measured. Doing so will require corrections to how it is conceptually defined and measured. We discuss these corrections and recommendations next.

Corrections and Recommendations

A key issue in creativity studies is that the borrowed concept of “self-efficacy” has been used to describe two distinct facets of creative confidence: trait-like creative confidence and state-like creative confidence. This approach is not aligned with Bandura’s (Reference Bandura2012) recommendations on clearly defining and measuring self-efficacy and potentially leads to a lack of clarity in understanding creative confidence within the field. Therefore, we have recommended (Beghetto & Karwowski, Reference Beghetto, Karwowski, Reiter-Palmon and Hunter2023; Karwowski et al., Reference Karwowski, Han and Beghetto2019a) that creativity researchers adopt the broader concept of creative confidence and clearly distinguish between its trait-like and state-like aspects.

Trait-like Creative Confidence. Trait-like creative confidence is a global belief that aligns with and incorporates existing measurement scales (described earlier). This is because it represents a more holistic judgment of one’s confidence to perform creatively in general or within a particular domain (e.g., science, business, sports, education, and the arts).

Trait-like creative confidence is more aligned with a person’s creative self-concept (Beghetto & Karwowski, Reference Beghetto, Karwowski, Karwowski and Kaufman2017; see also Marsh et al., Reference Marsh, Pekrun and Parker2019). It reflects general feelings and relatively stable judgments about one’s confidence to perform creatively. These judgments are based on the totality of past creative performances (e.g., “I am good at coming up with new ideas”) and comparative judgments (e.g., “My imagination and ingenuity distinguishes me from my friends”). As can be seen from these examples, our and others’ traditional measures fit nicely under this conceptual correction and therefore can still be used when studying creative agency beliefs.

This conceptual correction also allows creativity researchers to explore the nature of more global, trait-like beliefs – both on their own and in relation to more state-like beliefs. For example, Zandi and colleagues (Zandi et al., Reference Zandi, Karwowski, Forthmann and Holling2025) examined the stability of these beliefs. They found that trait-like creative confidence is generally stable in the short and moderate term, but it can change over the long term. Other researchers have examined the factors that influence these beliefs. Their findings show that creative confidence can be shaped by individual abilities (Lebuda et al., Reference Lebuda, Zielińska and Karwowski2021), personality traits (Karwowski et al., Reference Karwowski, Lebuda, Wisniewska and Gralewski2013; Karwowski & Lebuda, Reference Karwowski, Lebuda, Feist, Reiter-Palmon and Kaufman2017), and social influences (e.g., Karwowski et al., Reference Karwowski, Gralewski and Szumski2015).

Concerning measurement practices, we recommend that researchers use existing CSE scales or develop new ones when their goal is to understand the role of trait-like creative confidence. This includes examining how it contributes to a person’s broader creative identity, how it interacts with other creative agency beliefs in shaping creative performance, or when addressing questions related to this more stable and holistic form of creative confidence.

We also recommend that creativity researchers clearly acknowledge the trait-like nature of these measures when describing their methods and findings. Doing so will help advance the field’s knowledge and understanding of this important aspect of creative confidence.

State-like Creative Confidence. State-like creative confidence represents a more dynamic and performance-based judgment about one’s ability to attain various creative goals within a domain of creative activity. In this way, state-like creative confidence is more aligned with a person’s CSE (Beghetto, Reference Beghetto, Runco and Pritzker2020; Beghetto & Karwowski, Reference Beghetto, Karwowski, Karwowski and Kaufman2017). State-like creative confidence, much like self-efficacy (Bandura, Reference Bandura2001), is influenced by individual (psychological and physiological state, past performance), social (relatable models, social supports, social persuasion), and contextual factors (nature and ambiguity of the specific task).

As we have discussed, this is a more situationally dynamic creative confidence belief, which likely will be a more accurate predictor of within- and between-group differences in engagement, persistence, and performance on specific activities (Karwowski et al., Reference Karwowski, Lebuda, Beghetto, Kaufman and Sternberg2019b). One way to think about state-like creative confidence is that it becomes activated when researchers ask people to report on different types of creative activities and when they encounter those activities.

Moreover, state-like creative confidence will likely fluctuate when people engage with ill-defined (divergent thinking) problems. Such tasks lack predetermined solutions or single answers, creating increased ambiguity. As Bandura (Reference Bandura2012) noted, such ambiguity can challenge and potentially lower self-efficacy beliefs. Consequently, individuals’ confidence may rise and fall dynamically throughout the problem-solving process as they generate, evaluate, and abandon ideas without clear external criteria for success. Capturing these fluctuations is important because it offers insights into how individuals navigate uncertainty and manage the ambiguity of ill-defined problems.

This dynamic becomes even more pronounced in information-rich contexts. The amount and nature of information available during problem-solving can influence confidence. Although access to resources like the internet, collaborators, or AI tools might help resolve ambiguity and enhance confidence compared to working with limited information (see Faiella et al., Reference Faiella, Zielińska, Karwowski and Corazza2025), it can also introduce added complexity.

Individuals must sift through, evaluate, and integrate varied and conflicting information, which can influence confidence as they encounter challenges or breakthroughs. Therefore, documenting these real-time shifts in state-like creative confidence is essential for developing a deeper conceptual understanding of how individuals sustain effort and adapt their strategies while engaging with ambiguous creative challenges.

We recommend that creativity researchers continue to develop studies and measures of state-like creative confidence. This includes developing measures that are more aligned with Bandura’s (Reference Bandura, Pajares and Urdan2006, Reference Bandura2012) guidelines, like the example presented in Panel B of Figure 2. We also recommend building on Bandura’s guidelines to advance theory and research on creative confidence beliefs.

Rather than simply borrowing the concept and measures of self-efficacy, we recommend developing original research and knowledge that address questions unique to creativity studies. This approach will help foster growth in the field (Ambrose, Reference Ambrose2015; Berkovich, Reference Berkovich2020). We encourage researchers to develop more dynamic measures that can be used in conjunction with existing trait-like and state-like measures, like those displayed in Figure 2. These new measures could also complement other relevant tools, like those assessing other creative agency beliefs, physiological and emotional states, and perceptions of social support and pressures.

State-like creative confidence can, for instance, be assessed through dynamic measures administered at three critical points: immediately before, during, and again following task engagement. This temporal approach captures the dynamic nature of creative confidence across the creative process (see also Section 5 on creative self-regulation).

Dynamic measures are central to micro-longitudinal designs (Beghetto & Karwowski, Reference Beghetto, Karwowski, Beghetto and Corazza2019), which examine whether and how state-like creative confidence beliefs change throughout creative task engagement. These designs involve developing brief, minimally intrusive measures taken at various points – initially, during, and after task engagement. Such measurements provide more nuanced insights into the nature of creative confidence.

Micro-longitudinal approaches offer several advantages for understanding creative confidence:

1. Revealing why individuals with similar state-like “creative profiles” may demonstrate different creative performance outcomes;

2. Capturing temporal dynamics of creative confidence;

3. Allowing for examination of within-person variations across different contexts and tasks; and

4. Including behavioral assessmentsFootnote 2 to provide a more complete understanding of whether and how self-beliefs support actual creative performance.

This approach enables researchers to uncover subtle patterns of creative development that might otherwise go unnoticed (Beghetto & Karwowski, Reference Beghetto, Karwowski, Beghetto and Corazza2019). Its value lies in capturing the nuanced variations in creative confidence and in examining how confidence interacts with performance over time.

It also supports the view that creative confidence includes both trait-like and state-like elements. This allows researchers to observe how different aspects of confidence appear in real-world creative tasks. Finally, because there can be a disconnect between what people believe or value and how they actually perform, behavioral assessments can provide additional insight into the factors that influence people’s decisions to express and act on their creative agency.

Concluding Thoughts

This section has traced the conceptual evolution of creative confidence beliefs from early theoretical foundations through contemporary empirical approaches. We have discussed both the value and limitations of borrowed concepts while suggesting future directions for more precise measurement and conceptualization. These insights inform our discussion of creative centrality beliefs in Section 3, particularly regarding how creative confidence and centrality beliefs work in concert to shape creative agency.

3 Creative Centrality: Should I Do This Creatively?

Creative centrality beliefs are critical to our creative identity. Specifically, creative centrality refers to beliefs about the value, merit, or worth of creativity in relation to one’s broader sense of self (Beghetto & Karwowski, Reference Beghetto, Karwowski, Reiter-Palmon and Hunter2023; Karwowski et al., Reference Karwowski, Lebuda, Beghetto, Kaufman and Sternberg2019b). What we value is shaped by our individual and social experiences in the world and, over time, constitutes our unique personal identity (Hitlin, Reference Hitlin2003). Values reflect our desired goals, which vary in importance and serve as guiding principles for making decisions and acting in and across settings (Hitlin, Reference Hitlin2003; Morris, Reference Morris1956; Schwartz, Reference Schwartz1994).

A distinguishing factor between people who choose to exercise their creative agency and those who do not is whether they see creativity as central to their identity and their life (Dollinger et al., Reference Dollinger, Burke and Gump2007; Helson, Reference Helson1996). We further assert and have empirically demonstrated that these beliefs are central to people’s decisions about exercising their creative agency. Specifically, even if they believe they can be creative in a situation, they tend not to take creative action unless they see value in doing so (Karwowski & Beghetto, Reference Beghetto2019).

The development of creative identity (Beghetto, Reference Beghetto, Hoffmann, Russ and Kaufman2021a) can be thought of as progressing through several stages. It often begins with initial interest and enjoyment in creative activities (e.g., “I’m interested in creative writing”; “I like to write”). This interest may evolve to aspirational goal setting (e.g., “I want to become a novelist”). With sustained progress and continued engagement, the process can culminate in identity integration (e.g., “I am a writer”).

This developmental path typically unfolds over many years and continues throughout life, adapting as personal goals and circumstances change. However, setbacks, such as repeated manuscript rejections, can indefinitely interrupt or halt this progression (Beghetto & Dilley, Reference Beghetto and Dilley2016).

Creative Centrality

While the concept of creative centrality is generally understood, researchers vary somewhat in their specific definitions. Zielińska et al. (Reference Zielińska, Lebuda, Gop and Karwowski2024), for instance, define it as people viewing creativity as being vital to their self-perception and identity (including both personal and professional role identities; see also Huang et al., Reference Huang, Chi-Kin Lee and Yang2019). In contrast, Thomson and Jaque (Reference Thomson and Jaque2023) define it as whether people view the creative process as being essential for their personal meaning-making and well-being.

What is common to these different definitions of creative centrality is that they speak to the perceived value of creativity in people’s lives. Moreover, empirical work has demonstrated that indicators of these two conceptualizations of creative centrality are significantly related (see Thomson & Jaque, Reference Thomson and Jaque2023). Although there are nuances in how researchers have described the centrality of creativity, they all tend to agree that it serves as an essential aspect of how we view ourselves, our identity, goals, and actions (Dollinger et al., Reference Dollinger, Burke and Gump2007; Karwowski et al., Reference Karwowski, Lebuda, Beghetto, Kaufman and Sternberg2019b).

Should I Do This Creatively?

Creative centrality beliefs influence whether people choose to be creative when presented with the opportunity to do so. When individuals face an opportunity for creative action, they implicitly or explicitly ask themselves, “Should I do this creatively?” This question is not necessarily about external obligation or a universally “correct” approach. Rather, it represents a critical decision point rooted in creative centrality (i.e., the personal value and importance an individual places on creativity as part of their identity).

Because values serve as guiding principles (Schwartz, Reference Schwartz1994), this question reflects an internal decision: “Is acting creatively aligned with my core values and sense of self in this context?” It is a question of personal congruence and determines whether the individual will exercise their creative agency. Although creative centrality beliefs are essential to how people view themselves, they work in conjunction with creative confidence beliefs and other individual and socio-cultural factors when deciding whether to take creative action.

These assertions require further explanation and are briefly discussed in the sections that follow. A more elaborate discussion of the complex links between creative centrality, confidence, and the remaining elements of the creative agency puzzle is provided in Section 6, which offers a detailed overview of the CBAA model (see also Karwowski & Beghetto, Reference Beghetto2019).

The Relationship with Confidence Beliefs

Creative centrality beliefs have been conceptualized as more stable or trait-like than creative confidence beliefs (Beghetto & Karwowski, Reference Beghetto, Karwowski, Karwowski and Kaufman2017). Therefore, they can be thought of as being “transsituational” (Schwartz, Reference Schwartz1994), meaning they transcend specific situations (Hitlin, Reference Hitlin2003). Indeed, if we view being creative as so central to who we are, then we would be more likely to exercise our creative agency in and across situations that afford us opportunities to demonstrate our creativity.

However, this does not mean that people who highly value creativity will choose to be creative in every situation. As Ford (Reference Ford1996) explained, simply valuing creativity is not enough. Other factors can override this belief when it comes to taking creative action. Before deciding to exercise their agency, people need to see an alignment among the situation, their self-beliefs, and their relevant knowledge and abilities.

Indeed, deciding whether to act creatively is influenced by creative confidence beliefs, along with individual and sociocultural constraints and affordances present in each situation (Glăveanu, Reference Glăveanu2013). For example, an engineer may value innovative design. However, if they are facing a tight deadline, believe their manager prefers to avoid risk, and feel unsure about applying a new technique, they may choose a more standard, routine approach instead.

Creative centrality beliefs and creative confidence beliefs work together to establish a threshold for creative action (Karwowski & Beghetto, Reference Beghetto2019). When viewed through the lens of Expectancy × Value Theory (Eccles & Wigfield, Reference Eccles and Wigfield2002), people are most likely to exercise their creative agency when two conditions are met. They need to expect success (reflecting creative confidence) and value engaging creatively with the task. If either condition is missing, creative action becomes less likely. For example, if people do not believe they can be creative in a particular situation (regardless of the reason), they are unlikely to act creatively, even if they highly value creativity.

Conversely, even if people have confidence in performing a task creatively, they likely will not exercise their creative agency unless it aligns with their personal values (i.e., “Being creative is not important to me”). In this way, creative centrality beliefs moderate people’s decisions to exercise their creative agency, even when they have confidence in their ability to perform creatively. Our empirical work has provided support for this assertion.

In a series of studies (Karwowski & Beghetto, Reference Beghetto2019), we examined the role that creative confidence and creative centrality beliefs play in exercising creative agency (i.e., transforming creative potential into creative behavior). We found that although creative confidence beliefs mediated the link between creative potential and behavior, this link was not observed unless people also valued creativity above a certain threshold. These findings support our claim that for people to exercise their creative agency, they need to both believe they can act creatively (creative confidence beliefs) and believe they should (creative centrality beliefs).

Individual and Socio-Cultural Factors

Beyond creative confidence beliefs, various individual and socio-cultural factors can influence people’s decisions about exercising their creative agency on a project or task. Although valuing creativity represents a core aspect of our creative identity, people’s decisions about whether they should take creative action do not occur in a vacuum.

At the individual level, certain facets of personal identity complement creative centrality beliefs and the exercise of creative agency. These include openness to experience (Karwowski et al., Reference Karwowski, Lebuda, Wisniewska and Gralewski2013), curiosity (Karwowski, Reference Karwowski2012; Karwowski & Zielińska, Reference Karwowski and Zielińska2024), and valuing individual differences (Anderson, Reference Anderson2024; Dollinger et al., 2017). Other facets of personal identity may conflict with valuing creativity and exercising agency, such as valuing conformity, tradition, and security (Anderson, Reference Anderson2024; Dollinger et al., 2017). The relative strength of these competing facets plays a role in whether a person chooses to act creatively when given the opportunity to do so.

At the sociocultural level, complementary and conflicting messages and pressures about what is valued in a particular situation or setting can also influence whether people decide to exercise their creative agency. Motivation researchers (Ames, Reference Ames1992; Maehr & Midgley, Reference Maehr and Midgley1991) and ecological psychologists (Schoggen, Reference Schoggen1989) have long recognized the impact of both tacit and overt motivational messages and socio-psychological pressures in different environments. These factors shape people’s behaviors, including their decisions about whether they should act creatively (Amabile et al., Reference Amabile, Hennessey and Grossman1986).

If these motivational messages and behavioral pressures are highly salient and conflict with valuing creativity, then individuals who generally value creativity may still decide against exercising their creative agency in those situations or settings. This can happen when there is not sufficient support for creative action. Consequently, we assert that for people to decide they should exercise their creative agency in a given setting, one of two conditions likely needs to be met. Either their creative centrality beliefs must be more personally persuasive than the conflicting messages they receive, or the messages must be supportive of taking creative action.

These individual and social factors speak to the importance of people knowing when and when not to take creative risks, which involves assessing whether the benefits to themselves and others outweigh the potential costs. In other words, these factors influence people’s decisions about whether they will take creative action, which is the focus of the next section. Taken together, these theoretical assertions outline our view on how creative centrality beliefs, creative confidence, and individual and socio-cultural factors influence people’s decisions about acting creatively.

Although these assertions have a basis in theoretical and empirical work, much additional work is needed to test and refine them. For this work to continue to develop, it is important for creativity researchers to understand how to assess creative centrality beliefs and include those measures in their studies on creative agentic behavior.

Studying Creative Centrality Beliefs

Historically, creativity researchers recognized the importance of valuing creativity (Guilford, Reference Guilford1950) and asserted that creative people view it as a core value (Barron, Reference Barron1969; Dollinger et al., Reference Dollinger, Burke and Gump2007; Helson, Reference Helson1996). However, creativity researchers’ interest in assessing whether personally valuing creativity impacts creative performance is a relatively new area of focus. Although this is an emerging area of research, there are notable examples of creativity researchers studying the relationship between valuing creativity and creative performance.

Given that creative centrality beliefs constitute part of one’s personal identity, researchers have operationalized them as relatively stable and somewhat global. This is because our beliefs about the value of creativity are based on past experiences and socialization (Dollinger et al., 2017) in relation to one’s broader sense of self (Beghetto & Karwowski, Reference Beghetto, Karwowski, Reiter-Palmon and Hunter2023). Consequently, researchers tend to use more general measures when studying creative centrality beliefs.

Dollinger et al. (Reference Dollinger, Burke and Gump2007), for instance, used an existing values survey (Schwartz Values Survey; Schwartz, Reference Schwartz and Zanna1992) to measure university students’ value priorities. This survey includes an item asking participants to rate the importance of “Creativity (uniqueness, imagination).”

They also had participants complete a self-assessment of creative accomplishments (Hocevar’s, Reference Hocevar1979, Creative Behavior Inventory). A portion of the sample completed three scored creative products: a drawing product, a story product, and a photo essay. The creative centrality item was the best individual item predictor of self-reported creative accomplishments and a significant predictor of the composite rating for all creative products.

One of the most common ways creativity researchers assess creative centrality beliefs is through self-report items on the Short Scale of the Creative Self (SSCS, Karwowski et al., Reference Karwowski, Lebuda and Wiśniewska2018). Five items (e.g., “I think I am a creative person,” “My creativity is important for who I am”) from the scale assess the domain-general and trait-like nature of creative centrality.

Empirical work based on the SSCS indicates that people’s creative centrality beliefs tend to be relatively stable. While generally stable, this does not mean these beliefs cannot change over time or respond to interventions designed to help people recognize the value of creativity in their lives. Evidence suggests that these centrality beliefs tend to be stable in the short term but change as people age.

Karwowski (Reference Karwowski2016), for example, found that although these beliefs tend to be stable when measured in the short term, creative centrality beliefs grow from late adolescence to early adulthood and then decline in older adults. These results make sense, given that the centrality of creativity likely grows as people have more opportunities to exercise their creative agency during their transition to adulthood. Then, over time, the centrality of creativity may become more calibrated in later adulthood for people who do not view it as essential to their lives.

Regarding changes resulting from interventions, McVeigh et al. (Reference McVeigh, Valquaresma and Karwowski2023) examined the impact of an intervention focused on teaching about creativity and the creative process in an undergraduate screenwriting course. They found that the intervention significantly improved participants’ creative centrality beliefs (as assessed with the SSCS) and their creative performance. This finding makes sense, as the intervention likely helped students recognize the importance of creativity in relation to their screenwriting identity and goals. If participants initially lacked this connection, a course that clearly linked creativity to their chosen field would be expected to enhance their creative centrality beliefs.

We would therefore assert that although creative centrality beliefs are relatively stable, it is essential for researchers and practitioners to continue exploring the extent to which such beliefs vary and change because of life experiences and interventions. We would also recommend that additional work focus on how creative centrality beliefs vary across situations and tasks.

Given that prior research (Baer, Reference Baer2015) demonstrated that different levels of creative achievement tend to be contingent on different domains, it is plausible that creative centrality beliefs also vary in relation to specific performance domains. Indeed, highly accomplished creative teachers likely value creativity in teaching because teaching is so central to their identity. Those creative teachers, however, may not value creativity in activities other than teaching.

Future research could explore whether and how creative centrality beliefs vary in and across performance domains by using a combination of existing measures domain-general items (e.g., SSCS) as well as items tailored to specific domains (Beghetto & Karwowski, Reference Beghetto, Karwowski, Reiter-Palmon and Hunter2023), such as “Creativity is central to my identity as a [domain specific role].”

Concluding Thoughts

Valuing creativity and seeing it as central to an one’s identity are key factors in the decision to take creative action. As discussed, creative centrality beliefs are essential to creative identity and work with creative confidence beliefs and supportive environments to influence creative behavior. Understanding these beliefs helps clarify how personal identity and sociocultural factors shape creative action across everyday life, education, the workplace, and broader society.

Consequently, it is important that creativity researchers continue to develop research programs that contribute to our understanding of the role creative centrality beliefs play in supporting creative action. Creativity researchers can, for instance, study the conditions that help teachers and students recognize the value of exercising their creative agency in schools and classrooms. This includes examining the individual and socio-environmental factors that support the development of teachers’ and students’ creative identities, and identifying the conditions underwhich they choose to exercise their creative agency. Additional research in organizations and everyday life is also needed.

For example, what role do organizational leaders and environmental conditions play in reinforcing the value of creativity and encouraging employees to approach their work more creatively (Beghetto & Karwowski, Reference Beghetto, Karwowski, Reiter-Palmon and Hunter2023)? In the context of everyday life, researchers can continue to explore how engaging in creative activities can promote meaning (Kaufman, Reference Kaufman2023) and well-being (Putney et al., Reference Putney, Silver, Silvia, Christensen and Cotter2024). Indeed, deepening our understanding of creative centrality beliefs across various domains may help unlock people’s collective creative potential in their learning, work, lives, and society.

Ultimately, recognizing the importance of creative centrality beliefs underscores the idea that creativity is not just about ability but also about personal identity. By helping people see creativity as central to who they are, we can expect them to be more likely to take the risks necessary for creative action, which is the focus of the next section.

4 Creative Risk-Taking: Will I Do This Creatively?

Creative risk-taking beliefs refer to the willingness to think and act in new and meaningful ways when the perceived benefits to ourselves and others outweigh the potential costs (Beghetto, Reference Beghetto2019; Beghetto et al., Reference Beghetto, Karwowski and Reiter-Palmon2021). Creativity researchers have long recognized that the willingness to take risks is necessary for creative action (Haefele, Reference Haefele1962; Kaufman, Reference Kaufman2016). Creative action is risky because the outcomes of creative efforts are inherently uncertain (Beghetto, Reference Beghetto2019; Getzels & Jackson, Reference Getzels and Jackson1962).

Indeed, taking creative action often involves experiencing and working through setbacks and failures (Sternberg & Lubart, Reference Sternberg and Lubart1995; von Thienen et al., Reference von Thienen, Meinel and Corazza2017). Moreover, because creative outcomes have emergent properties (Sawyer, Reference Sawyer2012), it is difficult to predict the products, solutions, or outcomes of our creative endeavors. In fact, if the problem, process, and outcomes were well defined in advance, we wouldn’t need to act creatively.

Creative action is only necessary when we face ill-defined problems or attempt to bring something new into the world without a clear path or predetermined solution. In such situations, we need to decide (Byrnes, Reference Byrnes1998) that the benefits of engaging with uncertainty outweigh the potential costs and, if so, be willing to act on that decision (Breakwell, Reference Breakwell2014). This is the very definition of what is meant by taking acceptable or creative risks.

Conceptualizing and Studying Creative Risk-Taking

Despite extensive discussion in the creativity studies literature regarding the relationship between risk-taking and creative behavior, the field lacks a coherent framework for understanding this connection. Some researchers, for example, conceptualize risk as a predictor of creativity, whereas others view creativity as predicting risk-taking (Crepaldi et al., Reference Crepaldi, Fusi, Cancer, Iannello and Rusconi2024).

These inconsistencies are also reflected in mixed empirical findings. Some studies (Beghetto et al., Reference Beghetto, Karwowski and Reiter-Palmon2021; Charyton et al., Reference Charyton, Snelbecker, Rahman and Elliott2013; Harada, Reference Harada2020; Shen et al., Reference Shen, Hommel, Yuan, Chang and Zhang2018) have demonstrated links between indicators of creative risk-taking (e.g., willingness to take risks, risk tolerance, and risk-seeking) and creativity measures (e.g., creative activities and divergent thinking). Other research suggests more complex relationships. For instance, some studies found no significant correlation or only task- and domain-specific relationships between risk-taking and creativity (Jose, Reference Jose1970; Pankove & Kogan, Reference Pankove and Kogan1968; Tyagi et al., Reference Tyagi, Hanoch, Hall, Runco and Denham2017).

In their systematic review of fifteen studies, Crepaldi and colleagues (Reference Crepaldi, Fusi, Cancer, Iannello and Rusconi2024) attribute these conflicting results to three key factors:

1. Inconsistent definitions of creativity and creative risk-taking;

2. Methodological variations in measurement approaches (e.g., self-report vs. behavioral tasks); and

3. Unaccounted for sociocultural influences.

These findings underscore the need for a more robust theoretical framework to conceptualize and study the relationship between creative risk-taking and creative behavior.

Our updated CBAA framework (detailed in Section 6) offers a systematic approach to understanding the relationship between creative risk-taking beliefs and creative behavior. It addresses the theoretical gaps identified by Crepaldi et al. (Reference Crepaldi, Fusi, Cancer, Iannello and Rusconi2024). Building on previous sections, the CBAA framework incorporates precise definitions of:

Creative risk-taking beliefs: The willingness to act creatively when perceived benefits outweigh potential costs.

Creative agentic behavior: The intentional and self-directed capacity to enact creative actions within contextual constraints.

In the sections that follow, we build on those definitions and describe empirically testable factors that inform people’s beliefs and decisions to take creative risks (i.e., Will I do this creatively?). We also discuss theoretically aligned approaches for systematically investigating creative risk-taking within and across settings.

Will I Do This Creatively?

Our CBAA model positions creative risk-taking as a pivotal belief in determining whether people will try to do something creatively. However, the relationship between creative risk-taking beliefs and creative behavior is more dynamic and multifaceted than a simple, direct link.

Like the creative confidence and centrality beliefs discussed in Sections 2 and 3, creative risk-taking beliefs demonstrate both stability and situational variability. This dual nature – combining both trait-like stability and state-like contextual responsiveness – aligns with other agentic beliefs in our framework. We posit that the more trait-like features of creative risk-taking are informed by prior experiences with creative risk-taking and related agentic beliefs (e.g., creative confidence and viewing creativity as central to one’s identity).

Empirical evidence supports this assertion (Beghetto et al., Reference Beghetto, Karwowski and Reiter-Palmon2021). Findings from the study (N = 803) demonstrated that a general (trait-like) creative risk-taking orientation moderates the relationship between creative confidence beliefs and creative behavior. Risk-taking was measured using a self-report scale, with items such as “I like doing new things, even if I’m not very good at them” and “I try to learn new things even if I might make mistakes.” Creative confidence was measured using six global, trait-like items from the Short Scale of the Creative Self (Karwowski et al., Reference Karwowski, Lebuda and Wiśniewska2018). Creative behavior was assessed with the Creative Achievement Questionnaire (Carson et al., Reference Carson, Peterson and Higgins2005) and a modified version of the Inventory of Creative Activities and Achievements (Diedrich et al., Reference Diedrich, Jauk and Silvia2018).